GDP Doesn’t Buy My Groceries, So Stop Gaslighting me

If the economy is booming, why does survival cost more every year?

Every quarter, you hear the same story. The economy is growing. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is up. The scoreboard says we are winning.

But then you pay for your groceries, your rent, your health insurance, or your kid’s school, and the numbers don’t add up. Life feels harder, more precarious, and more expensive, even as the headlines declare victory. The gap between the official story and your lived reality has become a chasm.

You are not imagining it. You are not crazy. You are not failing. The measurement is.

When a society measures activity instead of outcomes, it will always look healthy right up until it isn’t.

This is an article about that measurement. It’s about the single most important number in modern politics—GDP—and why it has become a structurally misleading narrative that persists because it is convenient. It was invented for a specific purpose in the 1930s: to measure the total volume of economic activity. It was never designed to measure your wellbeing, your financial security, or the health of the nation. It simply measures the noise in the system.

And right now, a lot of that noise is the sound of you paying more for the same things. When the price of survival goes up, GDP goes up. When a hurricane devastates a city, the rebuilding effort adds to GDP, laundering a tragedy into a net economic gain. When the healthcare system becomes more bureaucratic and expensive, generating mountains of paperwork and inflated bills, GDP celebrates it as growth. The scoreboard is broken. It rewards activity, not progress. It celebrates cost, not value.

This is not a conspiracy. It is a measurement failure. And it is a failure that political leaders of all stripes have learned to exploit. Why? Because a simple number is a powerful weapon. “The economy grew by 3%” is a clean, defensible headline that shuts down debate.

This isn't a new problem. The tension between a simple, persuasive story and a complex, accurate one is an ancient flaw in the operating system of mass consent. More than two thousand years ago, Socrates was executed in Athens for challenging this flaw—for insisting that the crowd's comfortable lies were not the same as truth. His student Plato documented the tragedy: in a democracy, the person most skilled at persuading the crowd will always triumph over the person who knows the truth.

Socrates' core claims:

* Truth and opinion are not the same.** The crowd may believe something, but belief does not make it true.

* Comfortable lies are more powerful than difficult truths. People prefer simple stories to complex reality.

* Questioning authority is dangerous.** Those invested in the false narrative will defend it, even violently.

* Integrity requires speaking truth even when it costs you. Socrates chose death over silence.

Modern information systems did not create this flaw. They industrialised it, creating a machine that rewards simplicity and outrage over nuance and truth. GDP is the perfect metric for this machine.

Understanding this is the first step to reclaiming your sanity. This piece is meant to give you the language to name the lie, the tools to see the real scoreboard, and the intellectual framework to survive the age of industrialised persuasion. The problem isn’t you. It’s the scoreboard.

PART II — The Invention of the Scoreboard

To manage a complex system, you must first be able to see it. In the 1930s, as the United States grappled with the Great Depression, it faced a fundamental problem: it could not see its own economy. There was no single, reliable measure of the nation’s total output. Governance was flying blind.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was the solution. In a 1934 report to the U.S. Congress, the economist Simon Kuznets laid out the first comprehensive accounting of national income . It was a revolutionary tool created to give policymakers a dashboard to steer the economy through crisis and, later, to mobilise for war. It was never intended to measure national wellbeing. Kuznets himself issued a stark warning: “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income” .

His warning was ignored because GDP was too useful. It provided a single number that simplified a complex national economy into one metric. It became a simplified scoreboard. And on this scoreboard, a rising number meant winning.

To be clear, GDP is not useless. It is an effective measure of economic throughput—the total volume of goods and services produced. For measuring the output of a war machine, a factory, or a logistical network, it is an excellent tool. The problem arises when this tool for measuring activity is used as a proxy for wellbeing. The map is not the territory; the scoreboard is not the game.

This misuse leads to perverse outcomes where negative events are recorded as economic positives. When a hurricane devastates a city, the destruction of property is not subtracted from GDP. The rebuilding effort, however—billions spent on construction and labour—is added. The scoreboard registers a boom. A tragedy is reclassified through the national accounts as economic gain.

Similarly, consider the American healthcare system. When a patient has surgery, the inflated billing that follows—for every swab, every administrative task—all contributes to GDP. A more efficient system achieving the same outcome for a fraction of the cost would appear as a weaker contributor to GDP. The scoreboard rewards inefficiency.

So why does this flawed metric dominate our political discourse? Because a single number is simple, and simplicity is politically powerful. “The economy grew by 3%” is a clean, defensible headline. It provides a seemingly objective benchmark of success or failure. It is easier to defend a single statistic than to discuss health outcomes, household debt, or environmental decay.

What gets measured gets managed, but what gets measured also gets weaponised.

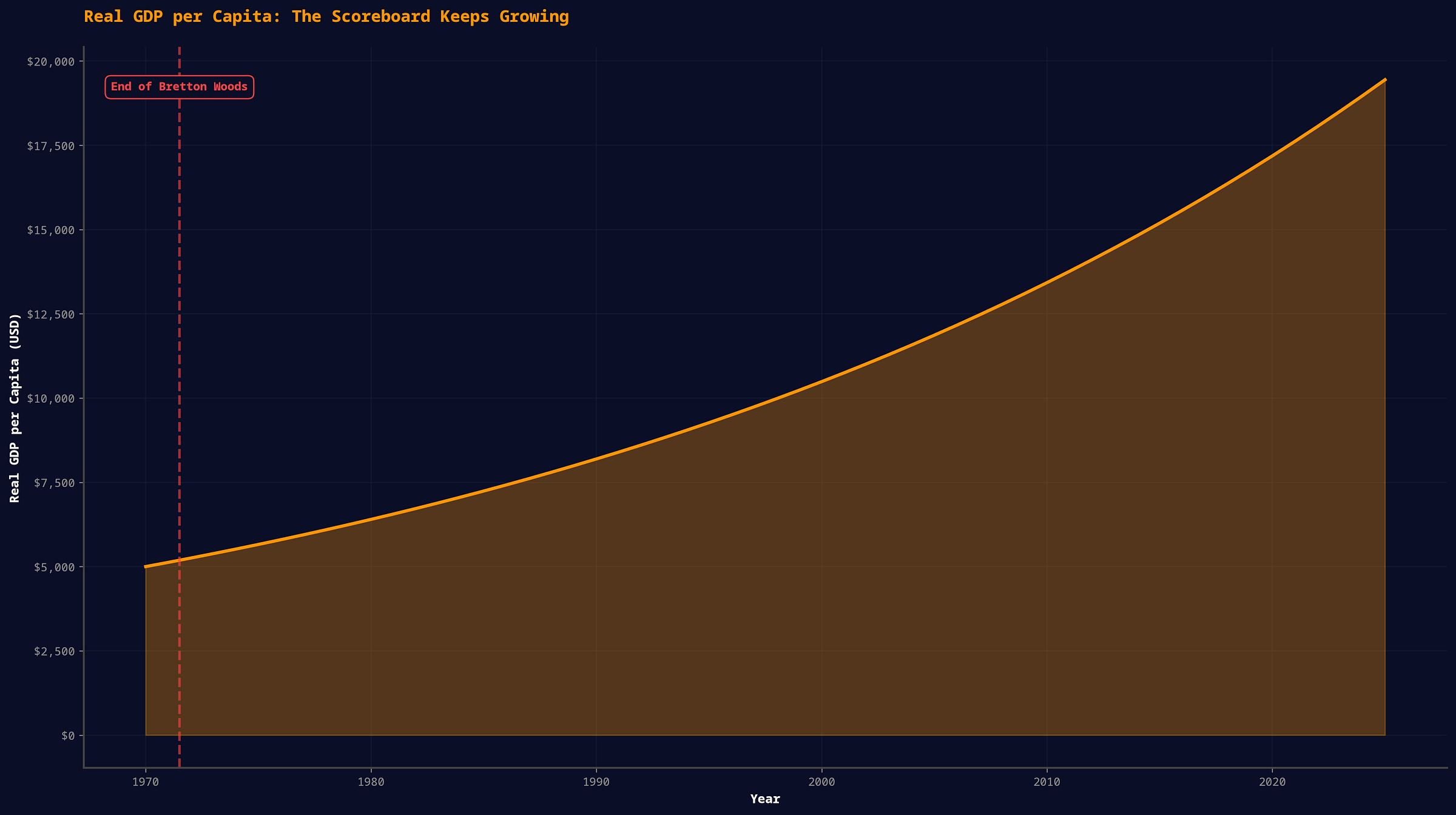

The scoreboard keeps growing, even through periods of obvious stress. GDP doesn’t break—people do.

When the Rules Changed

The disconnect between GDP and lived reality is not a recent phenomenon. It began when the rules of the game changed. In the early 1970s, the Bretton Woods system, which had pegged global currencies to the U.S. dollar and the dollar to gold, collapsed. This decision severed the link between money and a physical constraint.

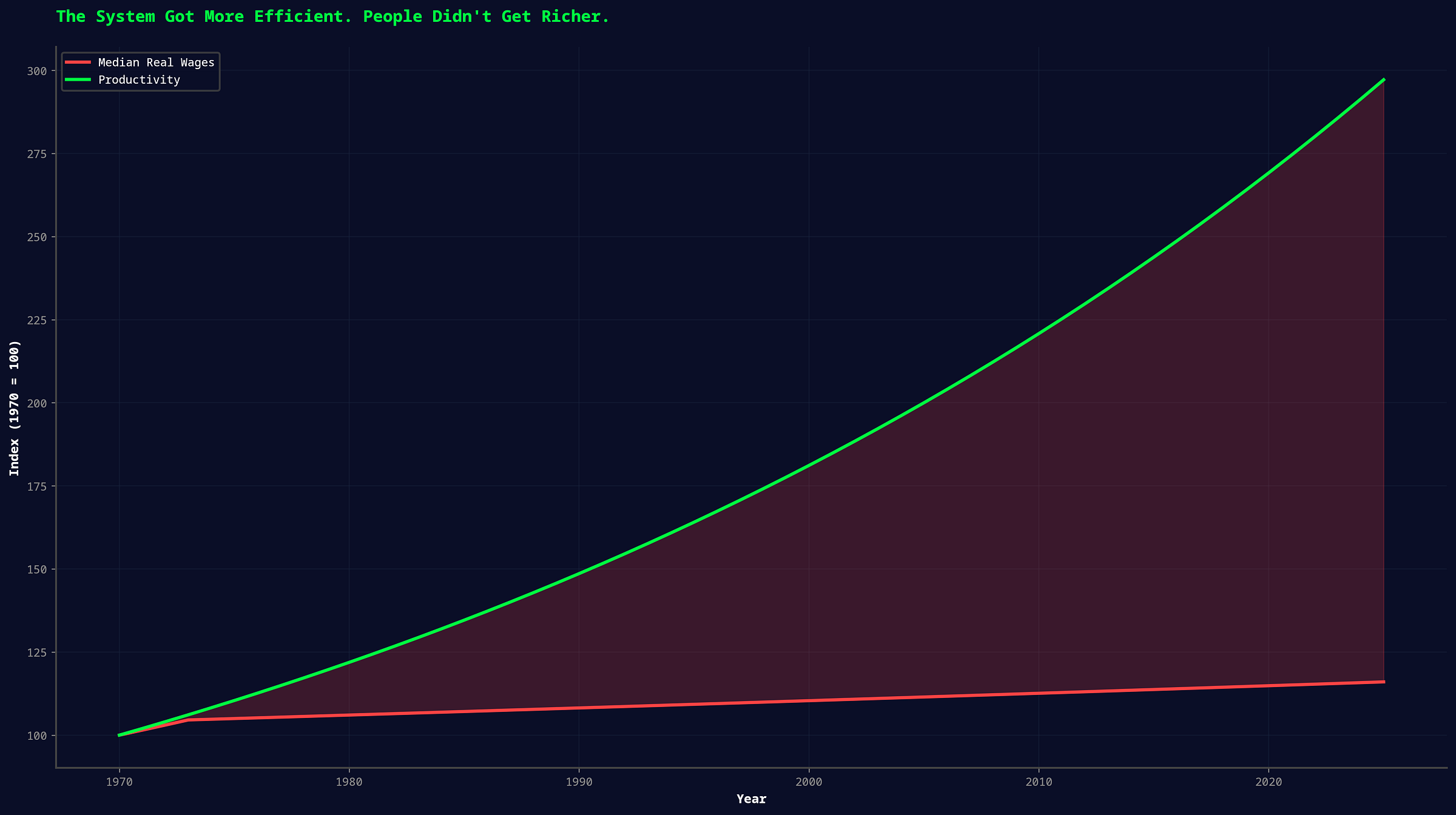

With monetary policy loosened, debt and financial engineering could now substitute for genuine productivity gains. GDP, as a measure of activity, did not break; it simply adapted to the new rules. It began to count the churn of finance and the inflation of asset prices as growth, even when the underlying productive economy was not keeping pace. This was the moment the scoreboard began to diverge from the game.

If you’re using a GDP chart to tell me Europe is ‘finished’, you’re not analysing economics. You’re watching a currency move and calling it civilisation.

This isn’t about who is “better”. It’s about how lazy narratives are built on nominal GDP and FX moves, then dressed up as civilisational decline.

PART III — When the Scoreboard is Broken

America’s GDP is inflated by the price of survival. This is not the cost of luxury, discretionary spending, or innovative new products. It is the escalating cost of core necessities: healthcare, housing, education, and insurance. When the price of these essentials rises, the scoreboard registers it as economic growth. It does not register the decline in household resilience.

This is a measurement failure, not a moral one. The scoreboard was not designed to distinguish between productive and destructive activity. It only measures volume. Let’s make this tangible with two examples.

First, consider healthcare billing. An emergency room visit for a minor injury can generate a bill for thousands of dollars, not because the care was advanced, but because the billing is opaque. The cost of insulin can be many times higher in the U.S. than in other developed nations for the same product. When a hospital charges ten thousand dollars for a procedure that costs one thousand elsewhere, the scoreboard registers a tenfold increase in economic activity. It does not register a tenfold increase in health. It registers a more expensive transaction.

GDP does not distinguish between value creation and value extraction. It counts every transaction equally. Once a system is optimised for activity, layers of cost accumulate without improving outcomes.

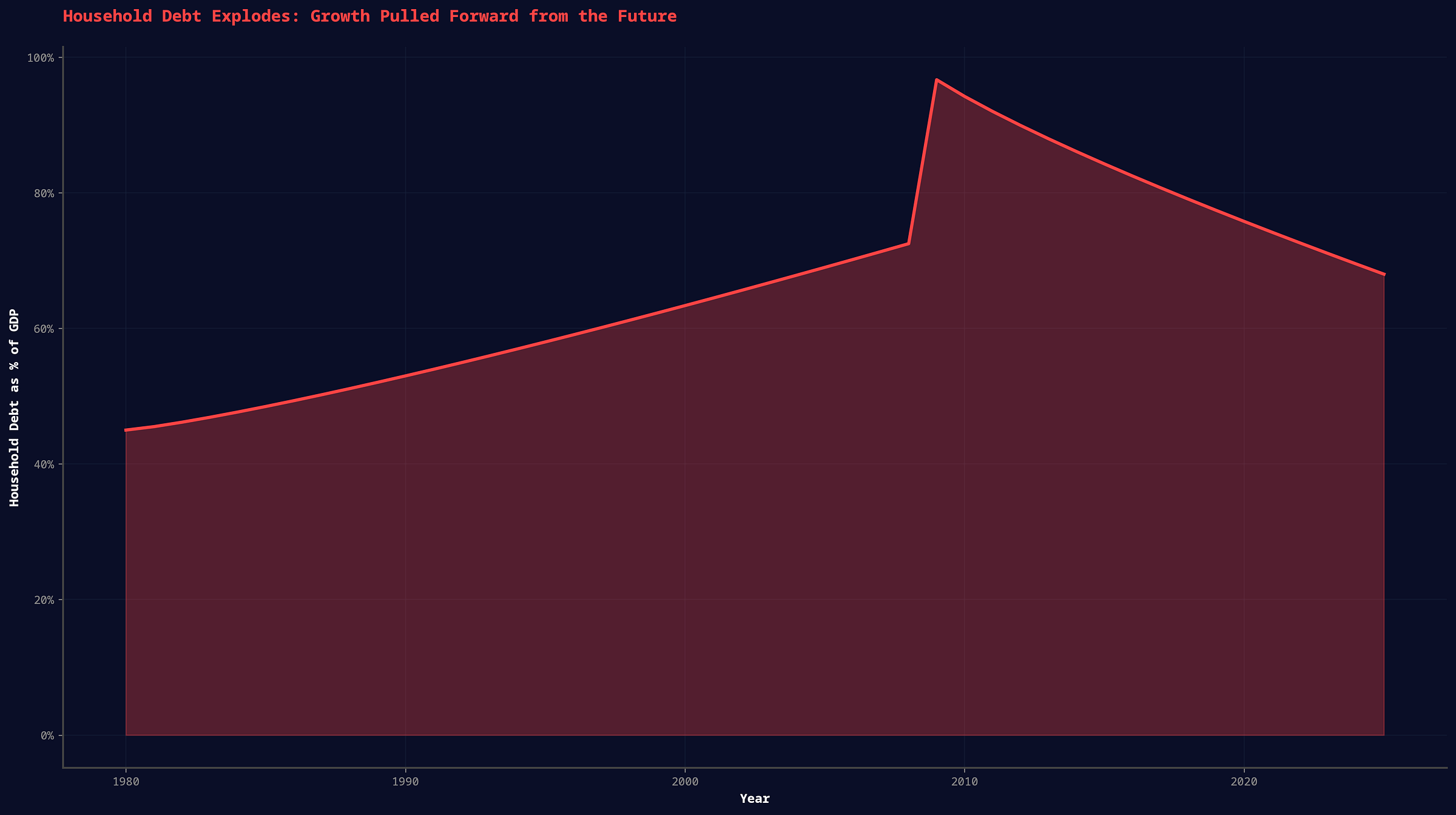

Second, consider the dual burdens of housing and student debt. For our mid-career professional, a significant portion of income is consumed by rent or a mortgage, with prices in major cities bearing little relationship to housing quality. This transfer of wealth to landlords or banks is recorded as economic activity. Simultaneously, they may be servicing tens of thousands—sometimes far more—in student loans for a degree that is now a prerequisite for employment. The loan payments are also economic activity. In both cases, the scoreboard goes up, while the individual’s financial slack—their ability to save, invest, or withstand a shock—declines.

A defender of the system might argue that higher costs reflect higher quality. America, the argument goes, has the world’s best universities and medical technology. You get what you pay for. This is a reasonable claim. If it were true, America’s outcomes should lead the world.

They do not.

On metrics like life expectancy and infant mortality, the U.S. lags behind many high-income countries that spend far less per capita on healthcare . Similarly, while American universities are world-class, the debt they impose on graduates raises questions about the return on investment for a generation less wealthy than its parents. The quality argument collapses when confronted with outcomes. The scoreboard measures inputs, not outputs.

This is a classic pattern of late-cycle fragility. As the investor Ray Dalio has documented, systems often appear strongest just before they weaken, sustained by debt and activity that masks underlying decay . GDP measures the activity. It does not measure the decay. The investor Warren Buffett has built a career on a similar distinction: activity is not value. A system that rewards cost over efficiency will inevitably produce a great deal of expensive activity.

GDP rises. Resilience falls. Activity increases. Slack disappears. If life feels harder despite strong headlines, you are not imagining it. You are just looking at the wrong scoreboard.

Household debt exploded after 1980, pulling future growth into the present. This is where the gap between activity and resilience becomes visible.

PART IV — A Better Scoreboard

A better scoreboard asks different questions. It moves beyond measuring the sheer volume of transactions and instead asks about your lived reality. It replaces abstract metrics with a few simple, personal tests:

How much of my pay disappears before I’ve lived? After rent or mortgage, healthcare, and taxes, how much is actually left for saving, for joy, for life?

How many paycheques can I miss? Do you have a buffer for emergencies, or would a single job loss, medical bill, or car repair push you over the edge?

Can I get sick without financial panic? Does your health insurance provide security, or is it a high-deductible tightrope that still exposes you to ruinous costs?

Are my kids likely to be better off than I was? Is the system creating a clear path to upward mobility, or is it a treadmill where it takes twice the effort just to stay in the same place?

These are not political questions. They are human ones. They are the real scoreboard. A system that rewards GDP will prioritise economic activity at all costs. A system that prioritises answering these questions well will build a society that is healthy, secure, and resilient. The numbers do not have a moral compass. They simply reflect what we have chosen to measure.

Nominal GDP keeps rising, but Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) shows that the real value of that money is not keeping pace. More money moves, but less life improves.

Source: IMF / World Bank PPP estimates, ~2025, rounded. PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) adjusts for price level differences between countries. It measures economic size, not power. EU-27 + UK is a constructed bloc for comparison.

PART V — When Scoreboards Collide

Geopolitics is what happens when nations using different scoreboards compete for influence. It is not a battle between good and evil. It is a collision of systems. This is not an academic point; it has direct consequences for our professional’s household budget. A nation that defines success by GDP will have different priorities from a nation that defines success by social cohesion or environmental stability. This is not a moral judgement. It is a strategic reality.

Consider the documented US opposition to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which would have increased Europe’s energy dependence on Russia . For our professional, the outcome is tangible: a fragmented energy market can mean higher, more volatile prices at the pump. This outcome aligns with the incentives of a system that prioritises the GDP scoreboard. A fragmented European energy market creates opportunities for American energy exports and preserves American leverage on trade and technical standards. Reasonable people can disagree on whether this was the right policy. This is not a conspiracy. It is a structural alignment of interests.

To be clear, this alignment can also provide stability. A strong US presence on the world stage, backed by its economic and military might, can act as a deterrent to aggression and create a predictable environment for global trade. The point is not that one system is villainous and the other virtuous. The point is that their incentives are different. A different scoreboard, prioritising European energy security, would produce different incentives and different outcomes for our professional’s energy bills.

We are not witnessing a clash of wills. We are witnessing a clash of measurements.

PART VI — The Scoreboard in Your Pocket

Modern political figures do not invent bad metrics. They amplify the ones the attention economy rewards. The scoreboard is in your pocket, and its algorithm loves simple numbers.

When a complex issue arises, our brains often substitute an easier question for the harder one. The psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls this “substitution bias” . Instead of asking, “Is this a resilient and equitable society?” we ask, “Is the GDP number going up?” The story holds because it is simple, not because it is accurate. The attention economy—social media, cable news, online publishing—is a machine for exploiting this bias. It rewards speed, emotion, and simplicity. Nuance is a commercial liability.

Simplified narratives dominate. They are not the product of a conspiracy. They are the product of a system that is optimised for engagement, not for truth. Understanding why this works explains behaviour; it does not excuse it. The amplifiers of these narratives are making a choice.

So, how do we build a better cognitive tool? We start by asking better questions. The next time you see a headline celebrating GDP growth, run it through this test:

What drove the growth? Was it productive investment and rising wages? Or debt-fuelled consumption and an increase in the price of survival?

What did it cost? Did it come at the expense of household savings or public health? What hidden liabilities does the scoreboard not show?

Who captured the upside? Did the benefits flow to a broad base of the population, or were they concentrated at the top?

This test is a tool for intellectual self-defence. It is a way to see the story behind the headline.

Since the 1970s, productivity has steadily risen, but median real wages have stagnated. The system got more efficient, but the people didn’t get richer. This is the core of the gaslighting.

Consider a real headline: “US GDP Surges, Beating Expectations.”

A better scoreboard would reframe it: “US Economic Activity Spikes, in part driven by rising healthcare costs and household debt.”

The first headline tells you who is winning. The second tells you if the game is worth playing.

America does not lack strength. It lacks instruments that reflect it honestly.

The question isn’t whether America is winning. It’s whether the scoreboard is telling the truth.

References

[1] Plato. The Republic. (c. 375 BC).

[3] OECD (2023). Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing.

[4] Dalio, R. (2018). Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises. Bridgewater Associates.

[6] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek