Part 1: The Vertical Economy. Capitalism won, so completely that it lost.

Debt, AI and the rise of off-world industry

Capitalism won, so completely that it lost. It outlived every serious alternative: feudal aristocracy collapsed under its own vanity, monarchies surrendered to parliaments, fascism burnt itself down, and communism lost the economic argument even faster than it lost the moral one. By the turn of the millennium, there was nothing left to debate. Markets weren’t just the organising principle of the economy — they became the organising principle of reality.

📑 CONTENTS — PART I.

The World Splits in Two

⚡ Introduction / Chapter 0 — The World Splits in Two

0.1 Capitalism Won, So Completely That It Lost

0.2 The Three Cushions Collapse

• Debt Stops Buying Growth

• Demography Flips

• AI Eats Labour

0.3 Inviting Marx into the Room

0.4 Europe’s Tragedy: Architect → Casualty

0.5 Two Operating Systems Emerge

• System A — Horizontal Capitalism

• System B — Vertical Industrialism

0.6 Why the Next Frontier Is Vertical

0.7 What This Book Does

🧭 1.1 What Exactly Split

1.1.1 Wealth as Credit vs Wealth as Capacity

1.1.2 China as the Hinge Between Systems

1.1.3 The Debt Superpower atop a Production Super-Organism

1.1.4 Demographics, Debt, and Synthetic Labour

1.1.5 Scarcity vs Abundance as Economic Architecture

1.1.6 When the Horizontal Map Is Complete

📆 1.2 The 1971–2025 Arc — How the World Changed Its Operating System Without Admitting It

1.2.1 The Quiet Revolution: From Gold to Promises

1.2.2 The Petrodollar Coup

1.2.3 Europe’s Quiet Deal: Welfare for Hegemony

1.2.4 When Debt Became Growth

1.2.5 Japan: The Canary in the Ledger

1.2.6 The China Shock

1.2.7 When the Maths Stopped Cooperating

• Shrinking Returns on Debt

• Demographic Inversion

• AI Threatens the Price of Labour

1.2.8 The Hidden Violence of a Soft System

1.2.9 What the Arc Leaves Us With

📉 1.3 The End of Linear Forecasting — Why Every Model Built in the Last 50 Years Is Now Useless

1.3.1 Why Forecast Models Became Fiction

1.3.2 The Curve Breaks: Debt vs Output

1.3.3 Demography Turns Upside Down

1.3.4 AI Breaks the Price Mechanism

1.3.5 Why Economists Still Draw Straight Lines

1.3.6 The West Is Model-Constrained

1.3.7 Scenario Thinking Replaces Linear Forecasting

1.3.8 Europe Loses Forecasting First

PART I — THE WORLD SPLITS IN TWO

Capitalism won, so completely that it lost.

1.0 — The World Splits in Two

Why the collapse of horizontal expansion, combined with the arrival of synthetic labour, forces civilisation to choose between two incompatible operating systems.

The Victory That Contained Its Own Defeat

Capitalism outlived every serious alternative.

Feudal aristocracy collapsed under its own vanity. Monarchies surrendered to parliaments. Fascism burnt itself down. Communism lost the economic argument even faster than it lost the moral one.

By the turn of the millennium, there was nothing left to debate.

Markets weren’t just the organising principle of the economy. They became the organising principle of reality. We didn’t argue about ownership models. We argued about interest rates and stock-based compensation. The revolution ended not with barricades, but with asset-backed retirement plans.

That victory was too clean.

Capitalism evolved for scarcity, not triumph. It assumes a world of limits:

scarcity of land scarcity of labour scarcity of energy scarcity of capital

Prices ration what you can’t have. Profit rewards the places where you find a way around the constraint. Scarcity wasn’t a flaw. Scarcity was the game.

For three centuries, the West did everything it could to outrun those limits.

The Three-Century Sprint

Europe wrote the blueprint: maritime trade, coal-powered industry, joint-stock finance, and the cheerful merger of state power and commercial ambition.

The United States industrialised the sequel at continental scale: oil, railroads, mass production, petrodollars.

China arrived late but ran the full cinematic universe in a single generation: a billion-person labour engine wired straight into Western demand.

It worked. Too well.

For fifty years, we kept the illusion of infinite growth alive through horizontal expansion:

more trade routes more shipping tonnage more outsourced labour more credit

When domestic productivity slowed, we borrowed. When wages rose at home, we moved the factory abroad. When local resources were depleted, we imported everything from somewhere with fewer lawyers.

Globalisation wasn’t a philosophy. It was a workaround.

Anyone who pointed out the arithmetic was labelled gloomy, unpatriotic, or French.

Eventually, the three cushions under the whole model collapsed at the same time.

1.0.1 The Three Cushions Collapse

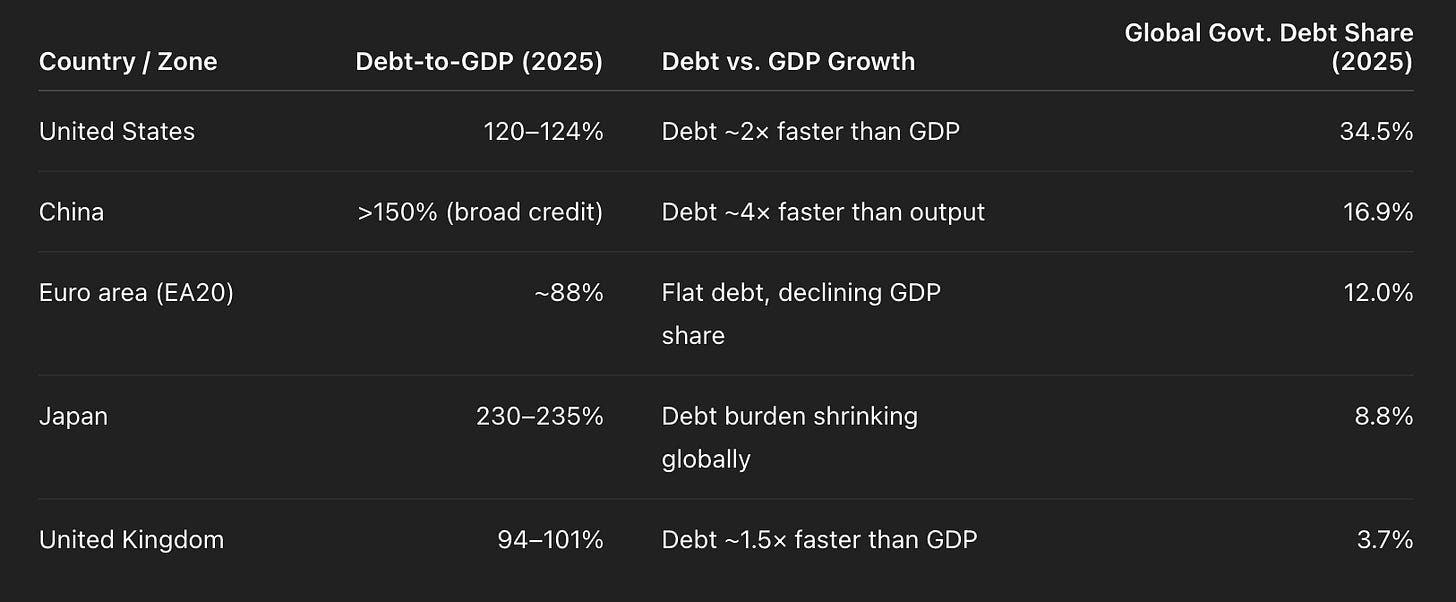

Debt Stops Buying Growth

The United States now adds one dollar of debt for something closer to half a dollar of extra GDP.

Japan has turned debt into a national hobby: it borrows from itself, lends to itself, and congratulates itself for the stability.

Italy’s debt mathematics no longer resembles economics. It resembles performance art.

For decades, debt was a bridge to the future. Then it became a habit. Then it became the future.

The extra growth from each new dollar of borrowing kept shrinking, even as the interest bill kept rising. The bridge stopped leading anywhere. It was just more bridge.

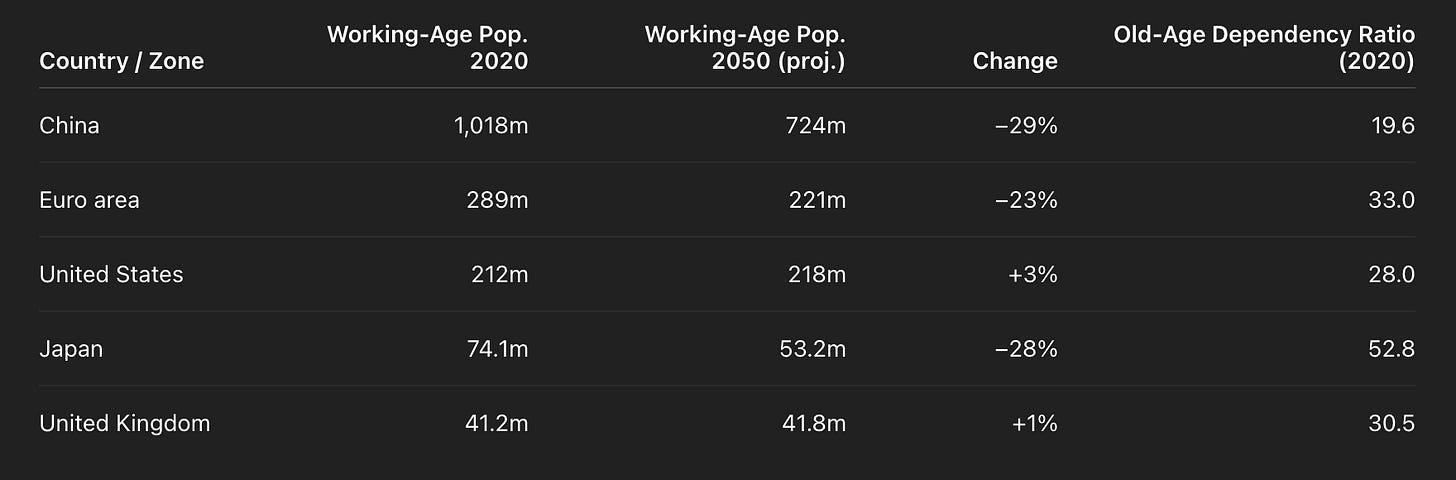

Demography Flips

China is shrinking faster than planners can invent euphemisms.

Germany spends more on pensions than defence.

France sets fire to its bins over retirement age—not because 64 is tragic, but because everyone can see the arithmetic:

fewer workers more dependents a tax base shaped like a coat hanger

For fifty years, growth was demographic momentum disguised as policy genius. Now the momentum is gone. And geniuses are in short supply.

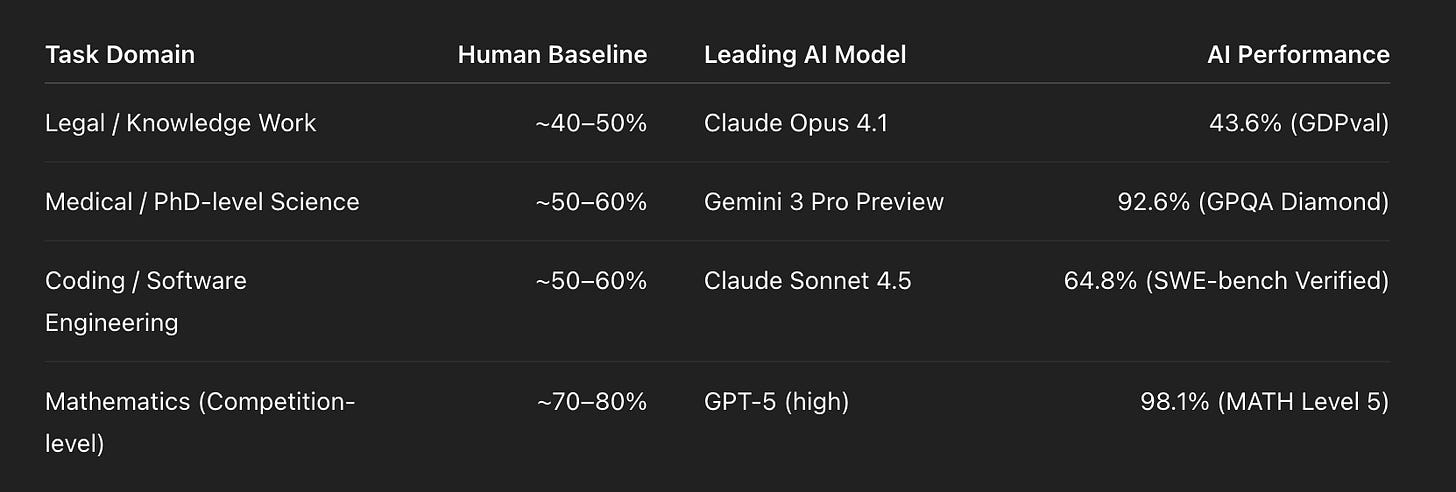

AI Eats Labour

The system-saving miracle arrives at the exact moment the system becomes fragile.

AI and robotics automate the very thing capitalism needs to function: scarce labour.

ChatGPT passes legal exams. Amazon warehouses hum with robots. Britain debates universal income before it has defined the economic model it belongs to.

This isn’t “job disruption.”

This is the removal of the foundational constraint that created the price system. Scarcity built capitalism. Synthetic labour is about to break it.

Worse, it’s a selective abundance.

AI makes cognition cheap in software while intensifying scarcity in hardware:

lithium copper water cooling grid capacity

Abundance in bits. Pressure in atoms. The more intelligence you run, the more you slam into physical limits.

1.0.2 Marx Walks Back On Stage

At this point, it’s worth inviting an old German into the room.

Karl Marx saw the paradox without seeing the machinery. He assumed capitalism would eventually collapse under its own contradictions: accumulated capital on one side, exploited labour on the other.

His logic wasn’t insane. His technology stack was missing.

He imagined a world where labour is cheap. We built one where labour is synthetic.

He predicted class conflict. We built a system where the class structure is ownership of compute, robots, and energy.

He thought revolution would come from scarcity. It will come, if it comes, from abundance:

a world where human work stops being the bottleneck but remains the thing people still need to sell.

Marx was wrong about the path, not the geometry.

1.0.3 Europe’s Tragedy: Architect → Casualty

Before the United States and China became the economic binaries of the 21st century, Europe was the engine of the world.

It designed the system:

industrial production imperial resource networks global finance the nation-state model

Then it destroyed itself. Twice.

The First World War bankrupted empires. The Second finished the job.

The United States inherited Europe’s architecture and funded Europe’s recovery on American terms: the Marshall Plan, Bretton Woods, the dollar as reserve currency.

The US became the system architect by default, because the original architect was lying in rubble.

From that moment, American grand strategy had a simple, ruthless constant:

Never allow Europe and Russia to become a single industrial-energy bloc.

A Europe plugged directly into Russian resources would have cheap energy, deep industrial capacity, and strategic autonomy. So NATO expanded east. Pipelines became battlegrounds. Every flirtation between Berlin and Moscow was treated in Washington as a potential geopolitical divorce.

China, watching from the margins, learned a different lesson:

If you can’t own the architecture, own the factories.

Europe rebuilt itself around a different idea:

security dignity institutions living standards

Not hegemony. Not empire.

It is the only region that genuinely tried to integrate people into capitalism before wealth. Which is admirable socially and disastrous geopolitically.

As the world split into two strategies—financial leverage and industrial leverage—Europe chose neither.

It sits between them today: too rich to be radical, too slow to be dominant. The continent that invented the game now plays it at a polite walking pace while the United States and China sprint.

Europe is neither writing the operating system nor leading the rebellion against it.

It is living inside its own invention.

1.0.4 The Split: Two Operating Systems

The world did fracture along ideology and power:

Washington vs Moscow democracy vs dictatorship “the free world” vs the rest

But beneath the flags and slogans, a quieter split emerged that now matters more.

A split of operating systems.

The world is crystallising into two economic logics.

System A — Horizontal Capitalism

debt-financed consumption asset inflation as prosperity financial exports demographic decline labour scarcity as price mechanism

A system built on credit and belief. This is the post-1971 Western model: the dollar, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, NATO.

A global supply chain priced in the logic of the spreadsheet, not the soil.

System B — Vertical Industrialism

mineral sovereignty energy abundance as strategy robotics as labour compute as capital production scale

A system built on resources and machines. This is the emerging BRICS+ model: China’s industrial stack at the core, India’s demographic engine, Russia’s energy leverage, Brazil’s resource basin, the Gulf’s sovereign compute build-out.

China sits slightly off-centre: financed with Western logic, built with Eastern ruthlessness.

One system runs on debt. The other runs on ore, silicon, electricity, and robots.

One expands horizontally, across continents. The other expands vertically, into the stack:

deeper mines higher grids colder data centres increasingly, off-planet

1.0.5 Why Vertical Matters — Without Science Fiction

We have reached the edge of the map.

There are no new continents to insert into the spreadsheet. No vast new labour pools to wire into supply chains. No politically viable way to keep scaling consumption with debt.

When the horizontal axis is exhausted, the next axis is vertical.

Not vertical in the corporate metaphor. Vertical in the literal one:

energy generation above the planet compute cooled by physics, not real estate manufacturing done where gravity is a design choice materials extracted where no one votes supply chains without human labour bottlenecks

The industrial loop that large-scale AI requires—cheap energy, brutal cooling, dense compute, vast materials—cannot scale another order of magnitude on a planet where every square kilometre has voters, a water table, and a grid constraint.

You can fight communities over one data centre. You can’t fight them over a hundred.

Off-world industry isn’t a utopian fantasy. It is the economic continuation of industrial growth once Earth’s limits become binding.

Degrowth imagines a moral retreat. Circular economics imagines recycling inside a fixed box. Redistribution imagines a fairer game of musical chairs.

But the chairs aren’t the game. The room is shrinking.

Capitalism doesn’t want to shrink. Technology doesn’t want to slow.

And history shows one reliable rule:

When a dominant economic logic hits a boundary, it finds a new territory.

The only territory left is upwards.

1.0.6 What This Book Does

This book is not about ideology. It is about geometry.

The shape of the world is changing because the surface area of economic expansion has collapsed at the same moment a technology capable of creating synthetic labour has arrived.

The result is a Great Bifurcation:

two incompatible operating systems emerging side by side one built on credit one built on minerals and machines

This collision will define:

debt politics energy wars robotics adoption sovereign AI the end of traditional labour universal wage models space as the new industrial basin

And the next decade will determine whether we get:

a controlled transition into abundance, or a messy collapse of a system that worked too well for too long.

The world splits in two.

And you are living in the moment the crack becomes visible.

1.1 — What Exactly Split

The world didn’t just split along ideology, values, or culture.

Those are the colours painted on the map.

It split along operating systems, which is much quieter and far more decisive. One civilisation compiles wealth through debt and consumption. The other compiles wealth through materials and production.

Everything else is commentary.

1.1.1 Growth From Leverage vs Growth From Output

For half a century, the West ran a system where growth came from leverage, not output.

You borrowed tomorrow so today looked prosperous. And as long as tomorrow kept arriving with lower rates and higher asset prices, everyone called it genius.

Critics were dismissed as pessimists, or worse—continental.

Across the board, politicians learned the same trick:

If voters want growth, but the economy can’t produce it, print the feeling of growth instead.

It worked, brilliantly. Until the arithmetic stopped cooperating.

Meanwhile, outside the Atlantic imagination, a different logic took root.

First Japan, then Korea, then China, and now the BRICS extended family built wealth in the old way:

dig refine build export

Their prosperity was not synthetic. It was welded, mined, soldered, and shipped. They operated on industrial leverage, not financial magic.

1.1.2 The Objection: “But China Has More Debt”

At this point a familiar objection arrives:

“China can’t be the alternative — it has even more debt than the West.”

That is where the axis has to change.

The interesting question is not how much debt a civilisation has.

It is what that debt metabolises into.

In the West, debt has been used to replace wages.

To keep consumption and asset prices rising even when productivity did not.

Debt → demand.

In China, debt has been used to replace labour.

To build ports, shipyards, factories, rail, refineries, EV supply chains, and increasingly, robots.

Debt → capacity.

Same fuel. Opposite engines.

Accountants count debt. Strategists count what it bought.

On paper, both systems are leveraged.

In reality:

One has mortgaged its future income to sustain the present.

The other has mortgaged its present population to build an industrial stack it intends to keep.

1.1.3 China as the Hinge

China is the hinge in this story.

Financially Western in its tools. Brutally Eastern in its outcomes.

It used the dollar world to sell into. It used Western taste for cheap goods. It used the post-1971 credit machine—not to join the club, but to rewire the supply chain in its own image.

The West exported dollars.

China exported factories.

1.1.4 The Real Split: Credit vs Capacity

So the split is not between indebted and prudent economies.

It is between:

a system where wealth is credit

and

a system where wealth is capacity.

Here’s the twist:

Both systems needed each other. One consumed what the other produced.

The West exported dollars. The rest exported everything else. As long as the dollar was the universal invoice, everyone played along.

America’s deficits were recycled into American assets, making its debt the safest place to store the savings of the very countries it was importing from.

Europe, exhausted by two suicides masquerading as world wars, quietly accepted the arrangement.

Less empire. More welfare.

It was a remarkable system:

a debt superpower sitting atop a production super-organism.

1.1.5 When the Inputs Changed

But no equilibrium lasts once the inputs change.

Demographics flipped. Fewer workers, more retirees.

Debt stopped buying growth. The extra output per unit of borrowing kept shrinking.

AI created synthetic labour. Scarcity—the engine of capitalism—stalled just as the physical inputs of AI made electricity, minerals, and land more contested.

You can negotiate with ideology. You cannot negotiate with a birth rate.

You can regulate markets. You cannot regulate arithmetic.

From 1971 onward, the West told itself that financial innovation was economic innovation.

The architects believed that as long as you could securitise anything—mortgages, student debt, tomorrow’s tax receipts—you were creating value.

China took notes, smiled, and built factories.

1.1.6 The Great Bifurcation

The result is what we now call the Great Bifurcation:

System A: wealth as credit

System B: wealth as capacity

One indexes prosperity in the price of assets. The other indexes it in the volume of steel.

One defends a currency. The other defends supply chains.

One treats money as power. The other treats materials as sovereignty.

They are now too far apart to converge.

Not because they disagree. But because their incentives and survival mechanisms have diverged.

A West that has replaced labour with leverage cannot suddenly become a manufacturer without imploding its asset markets.

And a BRICS bloc that has spent two decades building refineries, mines, fabs, and ports has no interest in returning to dependency because Washington rediscovered industrial policy in a white paper.

This is not a clash of values.

It is a clash of economic physics.

1.1.7 Why the System Didn’t Fail Because It Was Wrong

Capitalism ran its course so thoroughly that it exhausted the horizontal map.

It monetised every inch of land. Every hour of labour. Every future dollar of tax revenue.

There is nothing left to securitise except empty promises and political futures, neither of which compound very well.

And here is the uncomfortable insight:

The system didn’t fail because it was wrong. It failed because it worked.

It rewarded scale, consumption, and the financialisation of everyday life until there was nothing left to financialise.

1.1.8 The Only Two Options

When a system can no longer grow outward, it has only two options:

shrink

or

expand vertically

Degrowth is a sermon, not a plan.

Redistribution is theatre when the pie stops expanding.

Circularity helps, but you cannot recycle demographics. And you cannot recycle electrons that never had a grid.

And so the unspoken conclusion emerges:

The Earth model is complete.

Everything that can be extracted, organised, and monetised on this planet has already been fed into the spreadsheet. All horizontal frontiers have been eaten.

The next frontier has to go upward, not outward.

1.1.9 Why Space Is Arithmetic, Not Idealism

That is why space—whether you find it visionary or distasteful—is not idealism but arithmetic.

The ground economy is in structural saturation.

If your economic operating system needs scarcity to function, and AI abolishes scarcity in labour while intensifying scarcity in matter and energy, you either:

invent new scarcity

or

escape the gravity of the old one.

For now, the split is simple:

One world fights to preserve the scarcity engine.

The other invests in abundance infrastructure.

That is the bifurcation.

Not ideology. Architecture.

And architecture always wins.

1.2 — The 1971–2025 Arc

How the World Changed Its Operating System Without Admitting It

The world didn’t fracture in 2020, or 2008, or even with the fall of the Soviet Union.

The split began in August 1971.

The moment the US quietly suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, breaking the final mechanical link between money and the physical world.

1.2.1 The Genius of the Lie

The genius of the move was not in the economics.

Any half-sober economist could see the old system was unsustainable.

The genius was in the framing.

Nixon didn’t sell it as a revolution. He sold it as a technical adjustment. A temporary measure. A small correction to defend American jobs from “speculators”.

The lie was elegant because everyone wanted to believe it.

Gold was gone. Dollars remained sacred.

The church lost its god, but kept its rituals.

In that moment, capitalism quietly became ledger-based rather than resource-based.

Previously, money pointed to something scarce—a mineral hoarded in vaults.

After 1971, money pointed to something promised—future productivity.

And promises scale better than rocks.

1.2.2 How Each Region Responded

Europe, exhausted by two industrial suicides in a single generation, accepted this without fanfare.

Britain, still nursing the hangover of empire, pretended it was an equal partner in the new arrangement.

France grumbled philosophically, then traded critique for the convenience of the American umbrella.

Germany understood faster than anyone else that being an export machine inside a dollar world was the best geopolitical bargain in modern history.

Japan didn’t argue. It built factories.

China watched the whole thing like a chess player in a room full of poker players.

Everyone else was bluffing with paper. China was counting pieces.

1.2.3 The Petrodollar Coup

When the dollar stopped being redeemable for gold, it could have collapsed under its own weight.

It didn’t.

Because the US replaced gold with oil, and vaults with military bases.

The deal was simple, elegant, and devastatingly effective:

Saudi Arabia agreed to sell oil exclusively in dollars—in exchange for protection and American weaponry.

The rest of OPEC fell in line. Nobody argues with the navy that controls the sea lanes.

From that moment, the dollar was no longer backed.

It was enforced.

A barrel of oil became the new world reserve asset.

The global economy ran on energy, and energy was priced in dollars. This meant two things:

America could print the currency everyone needed, without suffering the inflation everyone else would.

Those dollars would return home as savings, investment, and Treasury purchases—funding the very deficits that created them.

It was a beautiful loop:

America spent the money. The world saved the money.

America ran deficits. The world ran factories.

Textbooks call it “globalisation”.

That’s polite language for tributary trade without the empire paperwork.

1.2.4 Europe’s Quiet Deal: Welfare for Hegemony

It is fashionable to mock Europe’s stagnation now, as if it were the product of incompetence or excessive bureaucracy.

But in the 1970s–1990s, Europe made a rational, almost moral choice:

It traded growth for peace.

It traded competition for security.

It traded ambition for equality.

After two world wars, any system that promised stability, pensions, and indoor plumbing without requiring aircraft carriers was progress.

America built hegemony.

Europe built welfare.

When the Cold War ended, Europe declared victory—which is the sort of thing you say when someone else paid for the victory.

The EU doubled down on its domestic model: harmonise, regulate, integrate.

That works perfectly. Until you need to adapt. Then adaptation looks like betrayal.

And in the background, another deal persisted:

Europe gained peace and energy access under an American umbrella, but at the price of real autonomy.

The unspoken rule was clear:

Europe could deepen its union, but must never fuse its industrial base with Russia’s resource base.

Every attempt at strategic friendship—gas pipelines, joint ventures, “modernisation partnerships”—hit the invisible tripwire where Washington’s interests and Europe’s independence diverged.

1.2.5 When Debt Became Growth

With the petrodollar established, the US unlocked the cleanest economic incentive ever invented:

If growth is measured in GDP, and GDP rises when spending rises, then borrowing is growth.

For forty years, “economic policy” was a spreadsheet trick:

Lower interest rates.

Inflate assets.

Make people feel richer.

Call it productivity.

It wasn’t a conspiracy. It was arithmetic.

Everyone from Reagan to Clinton to Obama rode the same wave.

Republicans financed consumption with tax cuts. Democrats financed consumption with credit expansion.

The slogans differed. The mechanism was identical.

And each cycle taught the same lesson:

If anything breaks, cut rates.

If rates hit zero, print money.

Every crisis became a stimulus event, reinforcing the belief that money had no consequences because consequences were always delayed.

A generation learned to treat debt as income you simply hadn’t declared yet.

1.2.6 Japan: The Canary in the Ledger

Japan was first to hit the wall.

In the 1980s, it looked unstoppable. Just as China does now.

Then demographics punched through the balance sheet.

Too many retirees. Too few workers. Too much debt. And no immigration culture to save it.

Japan tried everything:

zero rates negative rates QE fiscal spending public works even robot caregiving

What it couldn’t do was invent young Japanese people.

Europe followed the same arc, but slower.

China is entering it faster, but louder.

America faces it last. But hardest.

The message was there the whole time:

You can print money, but you can’t print youth.

1.2.7 The China Shock

When China entered the WTO in 2001, it wasn’t integrating into a Western system.

It was hijacking the operating logic and running it at scale.

The West believed it was outsourcing cost.

China understood it was outsourcing capability.

For two decades, every MBA case study, every Davos panel, every government trade mission pointed to the same hallucination:

Services would replace industry.

A neat story. Until COVID snapped supply chains and exposed the obvious truth:

You cannot download nitrile gloves, semiconductors, or antibiotics.

China didn’t “compete”. It absorbed entire industrial supply chains into one civilisation.

From ore to shipyard.

Europe watched this happen while writing ESG reports about stakeholder capitalism, and quietly ordering everything from Shenzhen.

1.2.8 When the Maths Stopped Cooperating

The turning point wasn’t cultural, political, or ideological.

It was mathematical.

By the mid-2010s:

The extra growth from each new dollar of sovereign debt kept shrinking, even as the cost of servicing that debt rose.

Not occasionally. Not in a recession. Everywhere—structurally.

Productivity flatlined, despite the digital revolution.

Demographics inverted, turning welfare states into pension lobbies.

And then—AI arrived, threatening the scarcity engine that justified capitalism in the first place and putting fresh strain on the physical infrastructure:

data centres grids minerals cooling

The 2020 pandemic didn’t create these forces. It accelerated them.

Governments printed more money in two years than they had in entire decades before.

And it worked, again. Until it didn’t.

Inflation returned not as a temporary shock, but as the consequence of a system where demand is printed and supply is imported.

You can stimulate consumption. You can’t stimulus-package a refinery, a mine, or a 20-year grid upgrade.

Capacity comes from:

mines factories ports energy networks the political will to do messy things for long periods

Western politics, built on short-term consent, is allergic to mess and duration.

1.2.9 The Hidden Violence of a Soft System

The most dangerous thing about the 1971–2025 arc is not the debt, the inequality, or the demographics.

It is the illusion that everything was “normal”.

Every politician claimed the system was sustainable.

Every central banker pretended the dial had infinite rotation.

Every economist spoke the language of models that hid the assumptions.

And citizens behaved accordingly.

Why save when asset prices go up?

Why worry when every crisis is “transitory”?

Why learn new skills when the old skills earn more by owning than doing?

For two generations, the West was raised on a logic that worked until it couldn’t.

That is not tragedy. It is structure.

1.2.10 What the Arc Leaves Us With

By 2025, three realities are unavoidable:

Debt stopped being leverage. It became life support.

The system now needs deficits just to stand still.

Demographics reversed the pyramid.

More voters want pensions than factories. People vote for their age, not their nation.

AI threatens the price of labour while demanding more energy and materials.

If labour is abundant, value extraction—the beating heart of capitalism—loses its rhythm.

None of these forces are ideological.

They are mechanical.

Which is why political debate feels deranged:

Everyone arguing about policies as if policies can reverse demography, restart productivity, or politely decline the arrival of machines that work without sleeping.

This is not a crisis of leadership.

It is a crisis of physics.

And this is where the bifurcation becomes visible:

The West tries to defend scarcity, because scarcity made money valuable.

The BRICS bloc bets on abundance, because abundance makes capacity sovereign.

It’s two worlds now—each rational within its own premises, each confused by the other’s.

One prints growth. The other builds it.

1.2.11 Europe: The Ghost in the Arc

And Europe? Europe is the ghost in this arc.

The civilisation that invented the world, and then slowly became a museum of its own triumphs.

It designed the institutions. It wrote the economics. It started the wars that shaped the borders. It created the ideas that justified the empires.

And then—it stopped wanting power, because power meant risk.

Europe’s brilliance is real:

It built the most humane society in human history.

A place where war is unthinkable, education is universal, and healthcare isn’t tied to employment.

That achievement now collides with a world where risk is power. And power is being accumulated by those who never took a decade off to write poetry about the end of growth.

Europe’s tragedy is not decline. It is satisfaction.

The satisfaction of a civilisation that solved comfort so thoroughly it forgot that comfort has a cost.

That cost is being called.

1.3 — The End of Linear Forecasting

Why Every Model Built in the Last 50 Years Is Now Useless

Economics, as taught from Cambridge to Chicago, rests on one quiet assumption that became invisible from overuse:

The future will look like the past, only slightly more so.

A little more growth. A little more productivity. A little more technology. A little more debt—offset, eventually, by a little more output.

We built entire institutions on that comforting slope:

central banks and their “neutral rates” pension systems projecting out to 2075 sovereign debt markets and risk models corporate valuation frameworks even climate scenarios and defence strategies

All variations on the idea that next year is a line drawn from last year.

That worked. Until the curve snapped.

1.3.1 History as Curriculum

In normal times, history is a reassuring teacher.

In transitional eras, history is the wrong curriculum.

Between 1971 and 2020, the world rewarded forecasters who could draw a straight line and punished those who saw the cliff at the end of it.

It wasn’t that the pessimists were wrong. It was that the system outlived the logic that should have killed it.

You could warn that debt was unsustainable. The bond market would prove you wrong for thirty years.

You could argue that offshoring hollowed out industrial capacity. The S&P 500 would rise anyway.

You could point to Japan’s demographic implosion and note the obvious implications. Growth models would simply “adjust the parameters” and carry on.

Linear forecasting is a narcotic:

It rewards the storyteller who says tomorrow is yesterday, plus 2%.

It treats the sceptic as a crank.

Then three things happened. Each of them fatal to straight-line thinking.

1.3.2 The Curve Bent: Debt vs Output

Somewhere around 2014–2016, the slope quietly broke.

You don’t see it in speeches. You see it in spreadsheets:

The extra growth from each new dollar of sovereign debt kept shrinking, even as the cost of servicing that debt rose.

Not occasionally. Not in a recession. Everywhere—structurally.

This is the moment the polite fiction collapsed:

Debt wasn’t a bridge to future productivity. It was the productivity.

We were no longer borrowing against tomorrow. We were borrowing to stop yesterday from being marked to market.

Once that flips, linear forecasting becomes performance art.

You can’t extend a line whose foundation has inverted. You can only admit that the axis changed.

The official models did not admit it. They smoothed it.

“Output gaps.” “Secular stagnation.” “Lower natural rates.”

Technical phrases for the same simple reality:

We had used tomorrow to finance today for so long that tomorrow had nothing left to give.

1.3.3 Demography Turned Upside Down

For 200 years, more people meant:

more workers more growth more consumption more tax revenue more everything

It was capitalism’s hidden engine.

When the demographic pyramid inverted—especially in Europe, Japan, and now China—the maths stopped working, but the models didn’t.

They did what models always do when reality is awkward:

They pretended it was incremental.

Ageing populations became:

a “headwind” a “pressure” a “challenge for sustainability”

As if the pension system were a slightly leaky pipe, not a sinkhole under the building.

Economists treated fertility collapse like a mild weather forecast, not a structural implosion.

If you can’t admit the population has stopped replacing itself, you can’t model anything:

not GDP not productivity not the tax base not defence budgets not housing not social stability

Yet every macro model still behaves as if 2025 has the same demographic logic as 1985.

This is delusion with footnotes.

1.3.4 AI Broke the Price Mechanism

Then came the anomaly that breaks the line entirely:

Labour became abundant.

Not labour markets. Labour as a category.

When a large language model can perform cognitive tasks, and a humanoid robot can soon perform physical ones, the scarcity condition that underpins every pricing model starts to fail.

Price is not a moral concept. It is a signal of scarcity.

If a machine can do the job without getting tired, sick, pregnant, unionised, educated, subsidised, or paid at all, the traditional link breaks:

more productivity → higher wages → more consumption

doesn’t bend. It snaps.

Most “AI optimism” imagines a productivity boom that lifts wages.

That is the romantic version of abundance.

The real version is colder:

Productivity rises.

Wages fall or stagnate.

Consumption shrinks—unless you redesign the system.

No model built between 1971 and 2020 knows what to do with potentially infinite labour and increasingly finite energy, cooling, and materials.

So they don’t. They assume it away.

They treat AI as a slightly better calculator, not a full-frontal assault on the scarcity of human effort and the feasibility of Earth-bound infrastructure.

This is why forecasts now feel like astrology with spreadsheets.

1.3.5 Why Economists Are Still Drawing Lines

It’s not stupidity. It’s incentives.

If you say the curve will break, you’re a heretic.

If you say the curve will continue, you get tenure.

If you present a discontinuity, you have to defend it forever.

If you present a straight line, you just have to survive until the next quarter.

Linear forecasting is not a method. It is a career strategy.

In polite circles, calling for discontinuity is rude, dramatic, even “political”.

Far safer to produce a graph that rises gently until 2050 and say, with a straight face, that productivity will recover because the model assumes it must.

This is the academic equivalent of medieval astronomy:

The planets move in circles because circles are elegant.

1.3.6 The West Lives Inside Its Old Models

The tragedy is subtle:

Leaders are not stupid. They are model-constrained.

Europe plans welfare expansion with 1980s demography.

America plans deficits with 1990s growth rates.

Japan plans fiscal supports with 2010s interest rates.

China plans industrial strategy with 2000s globalisation.

Every major power is acting rationally within a broken frame.

This is why debates sound insane.

People are arguing about policies that presume the old slope still exists.

The right blames the left. The left blames the right. Both are arguing inside a model whose premise died quietly around 2016.

When the maths snaps, ideology becomes cosplay.

1.3.7 Why Forecasting Now Feels Like Fiction

You can’t do straight-line forecasting when:

debt creates shrinking returns population shrinks labour is automated globalisation reverses energy becomes strategic compute becomes sovereign resources are weaponised supply chains fragment industrial capacity re-centralises and price itself begins to lose information content

This is not a “cycle”.

Cycles return to their starting point.

We’re not looping. We’re breaking orbit.

1.3.8 From Linear Forecasting to Scenario Thinking

Serious strategy is no longer about predicting a line.

It is about mapping discontinuities:

What breaks first?

What cascades when it breaks?

Who has the capacity to absorb the break?

Which systems survive in the new equilibrium?

That is why the next parts are structured around architecture, not ideology.

The world splits in two not because anyone voted for it, but because the logic of the system requires it:

A debt-based, consumption-driven system needs perpetual scarcity.

An AI-based, production-driven system produces structured abundance while demanding more raw energy and matter.

Those two logics cannot share a price system indefinitely.

One of them is lying about the future. The other is building it.

1.3.9 Why Europe Loses Forecasting First

Europe is the most elegant expression of the old model:

high education stable institutions universal welfare rule-based trade regulated markets linear planning by design

It is civilisation optimised for incremental improvement, not disruptive survival.

That was Europe’s genius. But genius is context-dependent.

When the slope was stable, Europe was the adult in the room.

When the slope bends, Europe is a museum of perfect compromises.

The models Europe believes in most devoutly are the ones that fail first when the line becomes a cliff.

The continent that once invented the future now risks becoming the place that keeps forecasting a past that no longer exists.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek