Part 2: The Vertical Economy. Debt was a bridge to the future. Then it became the future.

How the developed world replaced productivity with leverage — and why no democracy can admit the arithmetic

📑 CONTENTS — PART II

PART II — The Debt–Productivity Break

How the developed world replaced productivity with leverage, why the games stopped working, and why no political system built on short-term consent can admit the arithmetic.

2.0 — The Bridge Breaks

2.0.1 The Illusion of Infinite Slope

2.0.2 When Growth Became a Financial Product

2.0.3 The Moment the Maths Snapped (and Why Nobody Told the Voters)

2.0.4 Productivity Flatlines, Prices Rise

2.0.5 Incentives: Why Politics Rewarded Fantasy

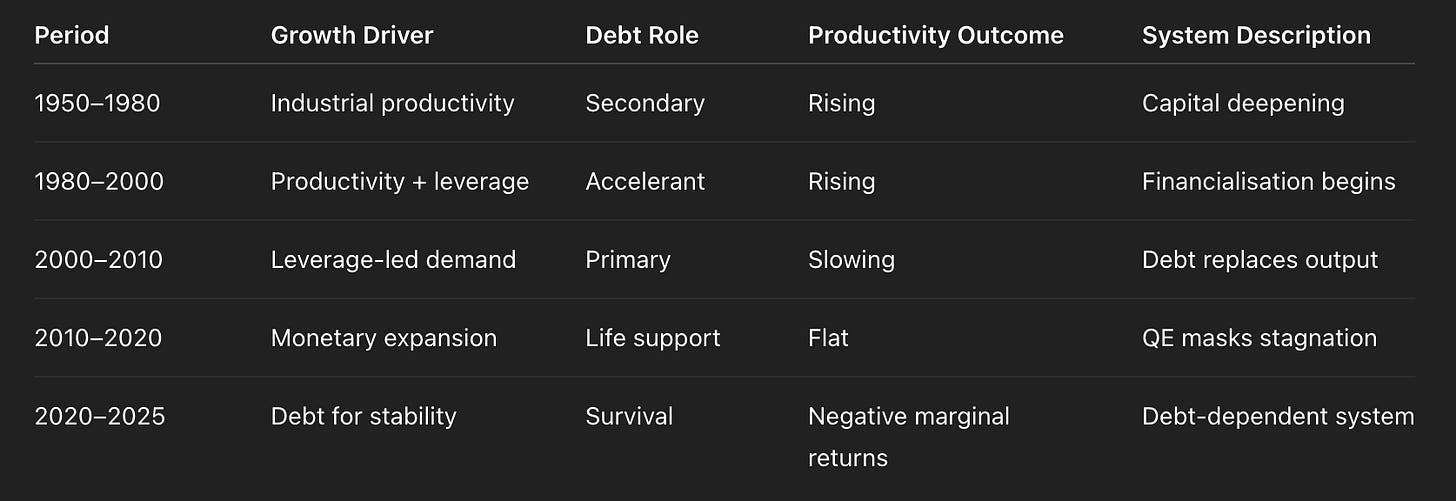

2.1 — The 50-Year Divergence

Debt and productivity used to be allies. Now they are enemies.

2.1.1 1950–1980: Productivity Drives Growth

2.1.2 1980–2000: Productivity Still Works, But Debt Joins In

2.1.3 2000–2010: Debt Takes Over the Engine

2.1.4 2010–2020: Debt Without Productivity

2.1.5 2020–2025: Debt as Life Support

2.2 — Why Debt Replaced Productivity

The incentives changed faster than the institutions.

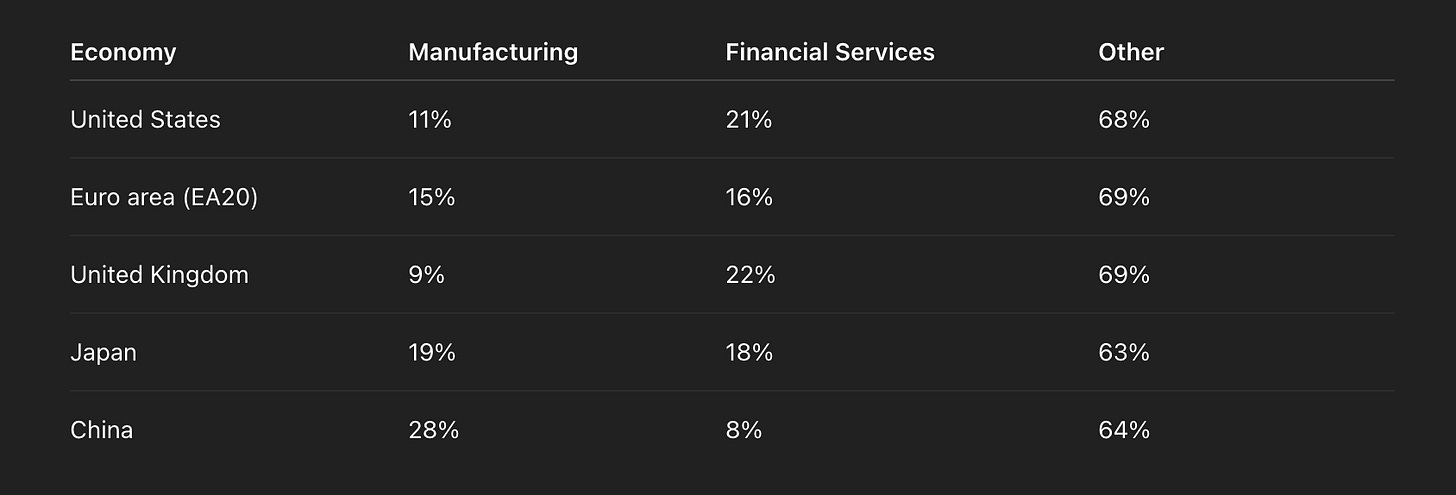

2.2.1 Globalisation Outsourced Industrial Complexity

2.2.2 Finance Becomes the Core Export of the West

2.2.3 Consumption as Industrial Strategy

2.2.4 Asset Inflation Masquerading as National Competence

2.2.5 Political Time Horizons Meet Compound Interest

2.3 — The Mechanism Nobody Debated

Every crisis taught the wrong lesson.

2.3.1 Reagan–Volcker: The Birth of Leverage Politics

2.3.2 Clinton–Greenspan: Equity as Welfare

2.3.3 Bush–Bernanke: Crises as Stimulus

2.3.4 Obama–QE: Debt as Social Stability

2.3.5 Trump–COVID: Printing the Feeling of Prosperity

2.3.6 Biden–Inflation: The Return of Arithmetic

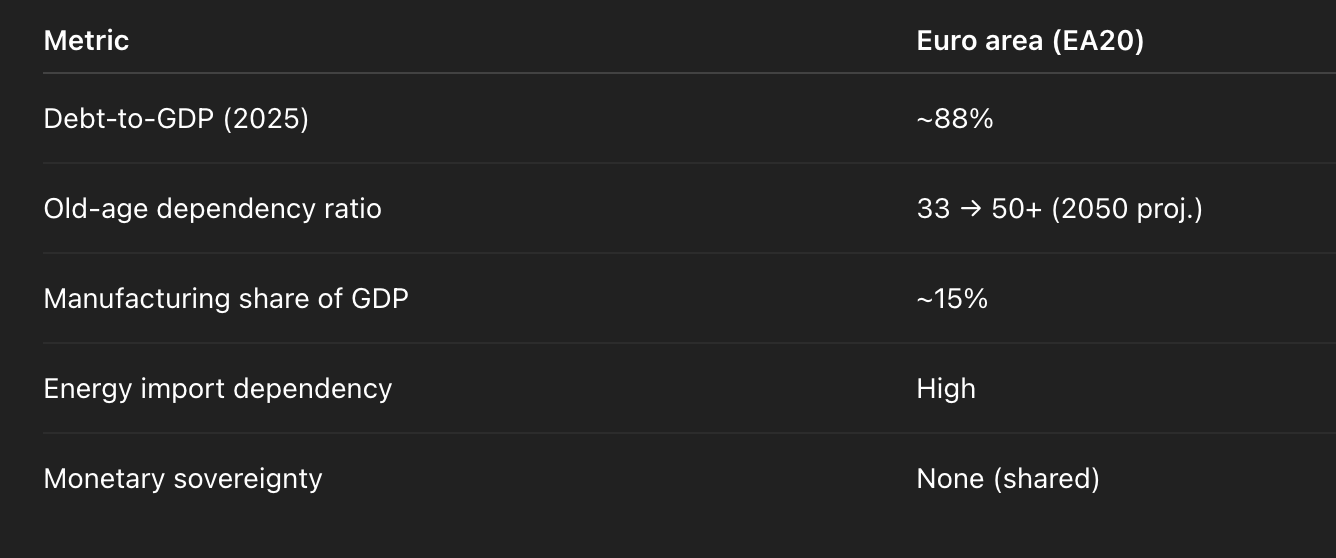

2.4 — Europe: The Elegant Wrong Turn

The only civilisation that consciously chose comfort over power — and now faces a world where power is the price of comfort.

2.4.1 Why Europe Didn’t Need Debt to Be Popular

2.4.2 Welfare as Growth Substitution

2.4.3 German Exports Inside a Dollar World

2.4.4 France: Philosophical Realism, Financial Faith

2.4.5 Italy & Spain: Debt Without Sovereignty

2.4.6 Eastern Europe: Industrial Memory Meets Demographic Collapse

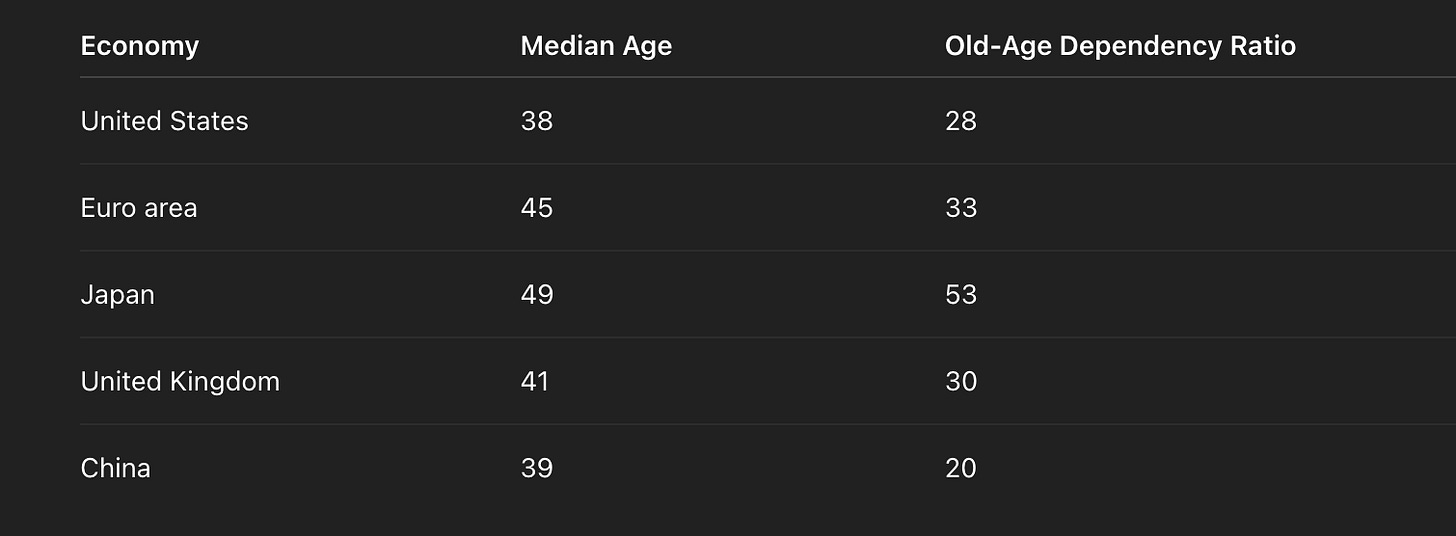

2.5 — China: The Mirror That Isn’t a Mirror

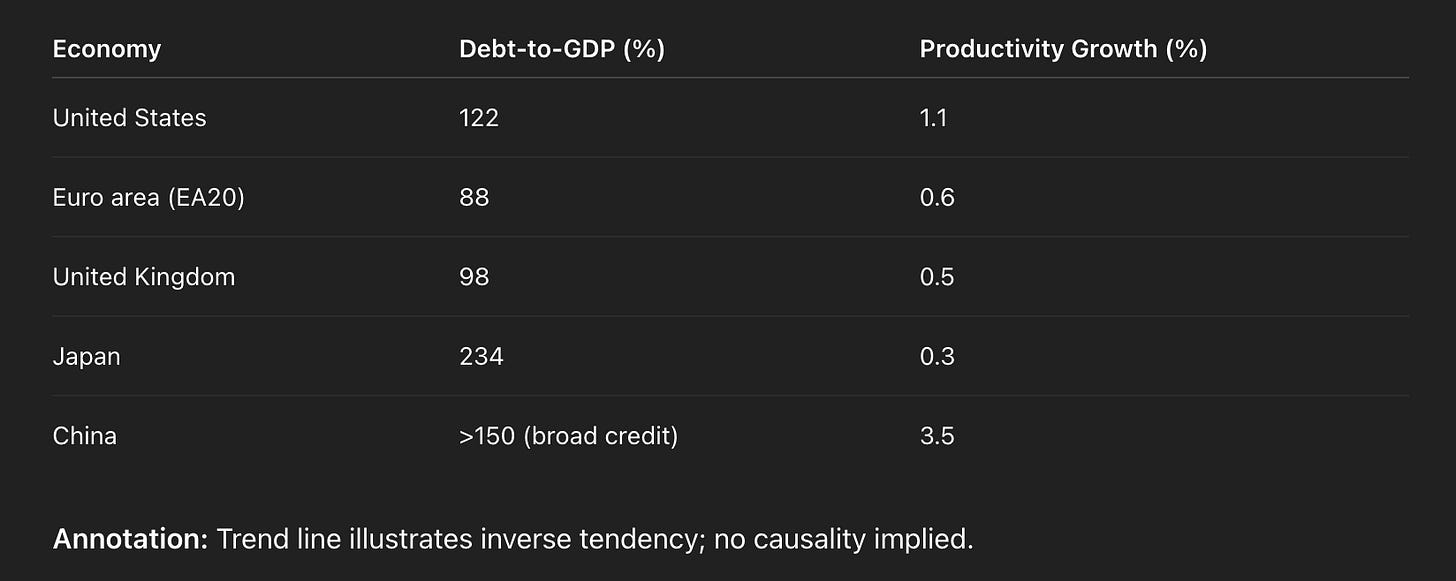

Yes, China has massive debt — but the system metabolised it into capacity, not consumption.

2.5.1 Why China’s Debt Looks Western but Isn’t

2.5.2 LGFVs — Borrowing Against Future Factories

2.5.3 Debt as Industrial Weapon

2.5.4 The Export of Factories, Not Goods

2.5.5 Demography: The Beginning of China’s Japan Moment

2.5.6 Why Synthetic Labour Came at the Perfect Time

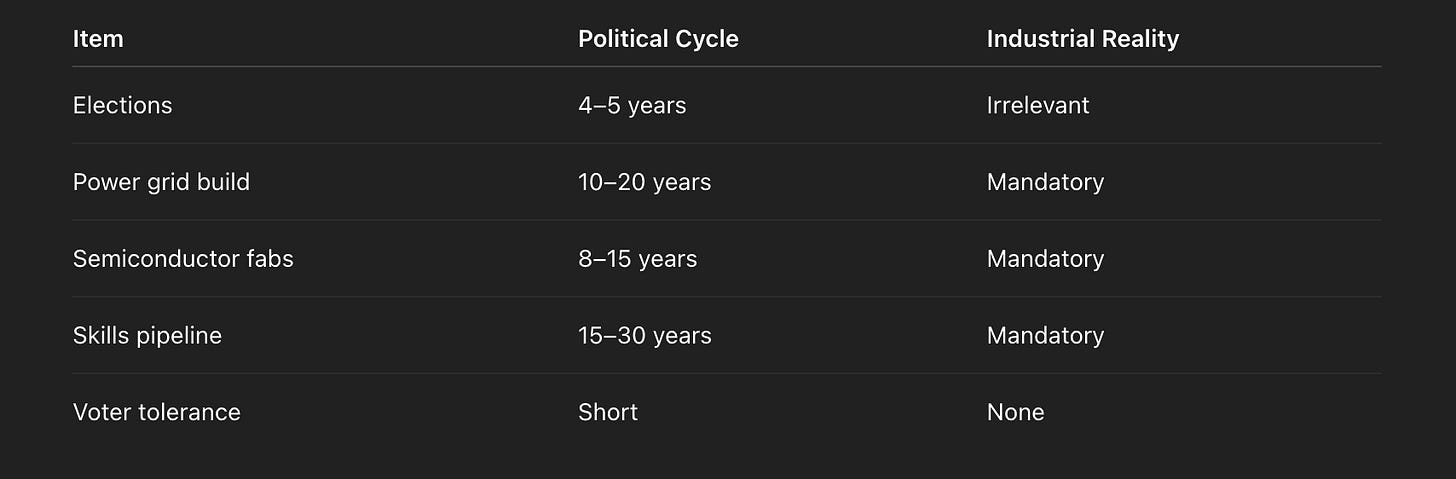

2.6 — The Great Political Constraint

No democracy can run an honest productivity campaign after two generations of leverage politics.

2.6.1 The Voter Time Horizon Problem

2.6.2 Short Elections vs Long Investments

2.6.3 Industry Requires Pain Before Prosperity — Politics Requires Prosperity Before Pain

2.6.4 The Iron Law of Retirement Voting

2.6.5 No Mandate for Reality

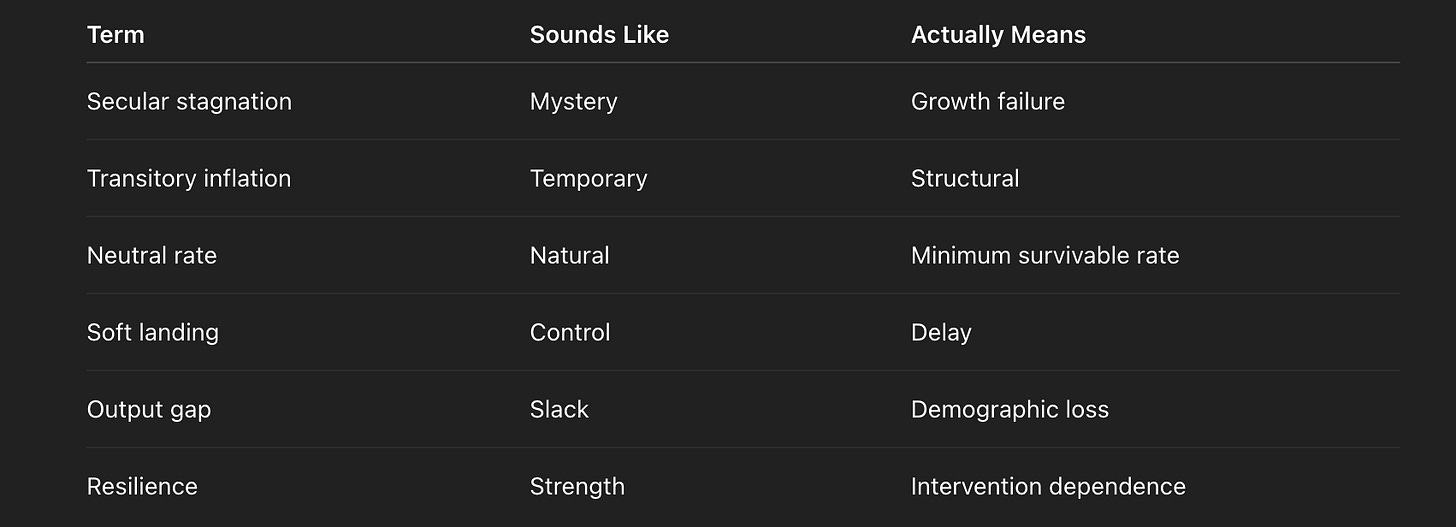

2.7 — The Terminology of Denial

Once the maths stopped working, the language evolved to hide it.

2.7.1 “Secular Stagnation”

2.7.2 “Temporary Disinflation”

2.7.3 “Lower Neutral Rates”

2.7.4 “Soft Landing”

2.7.5 “Output Gap”

2.7.6 “Resilience”

2.8 — The Break Becomes Visible

2025–2030 is when the illusion finally stops working.

2.8.1 Negative Debt Returns as Structural Reality

2.8.2 Productivity Growth Without Wage Growth

2.8.3 Labour Decouples from Pricing

2.8.4 Monetary Policy Loses Its Weapons

2.8.5 Capitalism’s Scarcity Engine Stalls

2.9 — The Choice Nobody Wants to Make

Shrink or go vertical.

2.9.1 Degrowth as Moral Sermon, Not Industrial Strategy

2.9.2 Redistribution Inside a Shrinking Pie

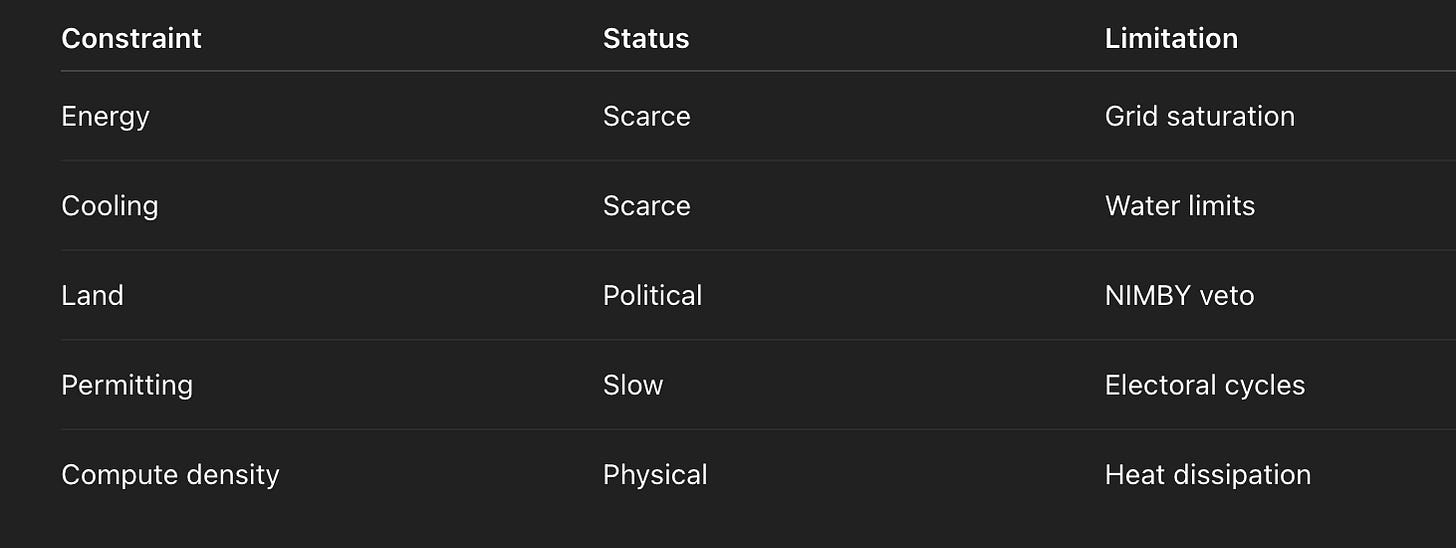

2.9.3 The Thermodynamic Limit of On-Planet Compute

2.9.4 NIMBY as Civilisational Constraint

2.9.5 Why the Only Remaining Frontier Is Upward

PART II — THE DEBT–PRODUCTIVITY BREAK

How the developed world replaced productivity with leverage, why the games stopped working, and why no political system built on short-term consent can admit the arithmetic.

2.0 — The Bridge Breaks

For fifty years, the developed world believed a simple story:

Borrow today, grow tomorrow.

It worked so well it became invisible—like oxygen, or ideology.

Governments issued debt. Companies leveraged up. Households mortgaged a future they assumed would be richer than the present.

Nobody questioned the slope of the line.

Growth had become a habit, not a hypothesis.

The Victory That Erased Its Own Warning Labels

The problem wasn’t that the model was wrong.

The problem was that it succeeded so completely that it erased its own warning labels.

Each decade added an extra layer of confidence, until eventually the model became faith with spreadsheets.

Delusion with footnotes.

And then, somewhere between Japan’s lost decade and America’s third round of quantitative easing, the maths quietly inverted.

Borrowing stopped pulling productivity forwards. It started cannibalising it.

Debt was no longer a bridge to the future. It became the future.

The additional growth generated by a dollar of debt shrank, even as the interest bill kept growing faster than output.

Economists call this “declining marginal return on credit”.

Politicians call it “stimulus”.

Central banks call it “market confidence”.

Everyone else just called it “normal”.

Nobody wanted to say the obvious out loud:

The model was over. Not morally. Not politically. Mathematically.

2.0.1 The Break: Slowly, Then All at Once

We lived through the break like you live through the end of youth.

Slowly, and then all at once.

At first it felt like a temporary anomaly: the financial crisis was a “once-in-a-century shock”.

Then it happened again. And again.

Each time, the cure was more leverage, because the alternative—admitting that the system had stopped producing productivity—was unthinkable.

Especially for politicians who, by design, have the life expectancy of a mayfly and the incentive structure of a gambler with someone else’s chips.

When a society confuses leverage with genius, reality arrives as punishment.

2.0.2 Productivity Flatlines, Wealth Rises

By the 2010s, productivity in the West had flatlined.

Not collapsed—that would have forced an honest conversation.

Just levelled off like a patient hooked to a ventilator.

Meanwhile, asset prices skyrocketed, and everyone felt richer—provided they didn’t look too closely at where the “wealth” was coming from.

Even today, people quote stock indices as if they measure national competence rather than liquidity pressure and pension-fund panic.

And yet, to be fair, the incentives made sense at the time.

The alternative to leverage would have been pain now for gain later.

Democracies don’t do that.

They do gain now and pain later, preferably after the next election cycle, and ideally after the current leadership is writing memoirs.

2.0.3 The Elegant Irony: Globalisation as Enabler

The irony is almost elegant:

The West tried to borrow its way around the consequences of globalisation—while globalisation itself was the reason it could borrow so cheaply.

China lent money so America could consume Chinese goods.

So China could build capacity.

So America could justify more borrowing.

A feedback loop that would have impressed Marx, if he wasn’t still being misquoted by people who last opened his books during university protests.

For a while, that loop felt like genius.

It wasn’t genius.

It was arbitrage at civilisational scale.

2.0.4 When the Loop Hit Physical Limits

By the late 2010s, though, the loop hit physical limits, not ideological ones.

Demographics turned. The West got older faster than anyone priced in.

The price of capital fell to zero, so pension systems needed asset inflation simply to stand still.

Stimulus became social stability, not economic policy.

And then AI arrived—not as magical abundance, but as something far more dangerous to the existing model:

Labour that doesn’t vote. Labour that doesn’t retire. Labour that doesn’t negotiate.

2.0.5 The Real Crisis: Scarcity Meets Abundance

You can almost feel the political tension:

A system designed to guarantee scarcity—to create prices, wages, and hierarchy—meets a technology that generates selective abundance.

That contradiction is the real crisis.

Not the moral panic about automation.

But the structural impossibility of a debt-based system surviving when the price of labour trends toward zero.

We’re not there yet.

But we can see it from here.

2.0.6 The Bridge Broke Quietly

And so the bridge broke.

Quietly. Mathematically. Without a speech.

There was no moment of national reckoning. No newspaper headline.

Just a gradual shift in the meaning of prosperity:

from making things to pricing things from productivity to liquidity from growth to confidence

2.0.7 The Simple Question Nobody Asks

Ask yourself a simple question:

If growth is real, why does it require constant injections of money to be visible?

If the answer is “we have a complex modern economy”—you’ve missed the point.

Complexity should compound productivity, not disguise its absence.

The real answer is much simpler:

We became debt-addicts with distinguished CVs.

Civilised. Sophisticated. Numerate.

But addicts nonetheless.

2.0.8 Why the System Can’t Stop

And addicts can’t stop—not because they don’t see the consequences, but because the consequences are already priced in.

If a country built its pension system on the assumption of 3% growth forever, then admitting 0.7% means political suicide.

So, the system lies.

Politely. Procedurally. With an index committee and an update to the definition of inflation.

2.0.9 The Only Two Answers

This is where Part I meets Part II:

The break wasn’t ideological. It was structural.

And now we have to ask the only question that matters:

What do you do when the bridge to the future has become the edge of a cliff?

There are only two answers:

Shrink the ambition of civilisation (the polite word is “degrowth”).

Build new industrial loops that don’t depend on terrestrial constraints.

2.0.10 The False Third Option

Most people pretend there’s a third option: “reform the old model”—by tweaking interest rates and making earnest speeches about innovation clusters.

That isn’t an option.

That’s denial with PowerPoint.

The West already tried to reform the system:

deregulation central-bank heroism supply-side tax theology QE masquerading as progressivism green subsidies without mines “AI strategy” without energy

It failed—not because the ideas were flawed, but because the physics of a crowded planet beats the ideology of a growth-addicted democracy.

You can’t push another order of magnitude of energy, compute, desalination, and industry through the political bottleneck of land with a voter, a neighbour, and a water table.

That’s the line people will remember:

The industrial loop AI requires cannot scale another order of magnitude on a planet where every square kilometre has a voter, a grid constraint, and a water table.

2.0.11 Why the Model Failed

This is the point of Part II:

The model didn’t fail because people were stupid. It failed because it worked too well for too long, until success itself became the constraint.

Now the bridge is gone.

And the only way forward is upward.

2.1 — The 50-Year Divergence

Debt and productivity used to be allies. Now they are enemies.

The Swap: Constraints for Narratives

The arc begins in 1971, not because Nixon was a visionary economist, but because he did the most consequential thing without fully understanding it:

He swapped constraints for narratives.

Gold was a brake. Promises are an accelerant.

Once the dollar unhooked from metal, the whole world followed.

Reluctantly at first. Then enthusiastically. Then blindly.

From that moment, growth became a story you could finance, not a reality you had to produce.

2.1.1 The Psychological Trick of Late Capitalism

For a while, it worked almost magically.

Debt wasn’t just money borrowed from the future. It was a way of dragging the future into the present.

Consumption jumped forward a generation:

houses cars universities healthcare pension expectations

Futures that didn’t exist yet, brought forward with cheap leverage.

That’s the psychological trick at the heart of late capitalism:

The future feels real when you can spend it now.

The problem is that futures have to arrive eventually.

And by the time they did, they were already spent.

2.1.2 The First Divergence: Debt Outruns Productivity

In the 1980s and 90s, the curve was still believable.

Each new unit of debt added something to productive capacity:

infrastructure telecommunications the digital backbone

The world got more efficient as it got more indebted.

By the late 2000s, the curve bent the wrong way.

Debt kept rising. Productivity stopped keeping up.

Not because machines failed or people lazed—but because the frontier was already built.

You don’t get another productivity revolution from:

giving everybody their fifth screen giving everybody their third degree giving everybody a bigger house 40 miles from the office

Those are lifestyle improvements disguised as investment.

The accountants called it GDP.

Reality called it consumption.

2.1.3 The Tragedy of the Western Demand Model

In a healthier model, that judgement doesn’t matter.

Consumption can stimulate demand, which stimulates production.

But when production has already globalised, and the cheapest factory is now twelve time zones away, consumption in London does not create jobs in Birmingham.

It creates capacity in Shenzhen.

That’s the quiet tragedy of the Western demand model:

We borrowed to consume. China borrowed to produce.

Over half a century, you get two different worlds:

one measures wealth in asset prices

the other measures wealth in what it can build

2.1.4 What Debt Actually Bought

China’s debt is real—enormous, opaque, dangerous.

But it bought capacity:

ports shipyards power lines rare-earth refineries industrial clusters EV supply chains 30 million engineers

When that debt is gone, the capacity remains.

When Western leverage deflates, the wealth vanishes with it.

Accountants count debt.

Strategists count what it built.

That is the divergence.

Not moral. Not ideological. Structural.

2.1.5 Europe: The Architect Becomes a Satisfied Client

Europe didn’t decline because it failed.

Europe declined because it succeeded.

Once the welfare state was built, the incentives shifted from ambition to preservation.

Europe solved the hardest problems:

healthcare education infrastructure rule of law

And then lost the appetite to build the next layer.

The victory became the anaesthetic.

That’s why European decline feels polite.

It isn’t collapse. It’s satisfaction ossified into stagnation.

The history books won’t record riots and revolutions. They’ll record missed decades.

2.1.6 The Unspoken Constraint: The Washington Tripwire

Add one more unspoken factor:

The US never allowed a Europe–Russia industrial union.

Washington spent 30 years ensuring the continent’s energy and industrial base never fused with Russia’s resources and market depth.

Because if they did, Europe wouldn’t be a client. It would be a pole.

That is not paranoia. It is policy. And it is public record.

Europe is the only civilisation that built the world twice:

first through empire then through the post-war institutions that defined modern global order

And yet, today, it plays defence while the new operating systems are built elsewhere.

2.1.7 The Second Divergence: Demography Flips

Japan was the canary in the ledger.

The first society to discover that retirees don’t generate growth.

They just hold assets that must be inflated to prevent political crisis.

When Japan deflated, it entered a polite depression.

Not dramatic. Not cinematic.

But slow, bureaucratic, and financially suffocating.

The West laughed politely at “Japanification”.

And then quietly copied it:

falling birth rates ageing electorates pension systems that assume growth forever asset markets whose job is now to disguise the lack of growth

When a country becomes a balance sheet with national anthems, its politics become absurd.

Everything becomes about a number nobody can publicly question:

The rate at which tomorrow must be better than today.

2.1.8 The Third Divergence: AI Eats the Price of Labour

This is where the debt-economy meets its natural predator.

A system built on scarcity—the price of labour, the price of time, the price of credentials—collides with a technology that makes certain forms of labour effectively infinite.

Not everything becomes abundant.

The important things become scarce:

lithium transformers water grid capacity people young enough to work in mines and factories

AI creates abundance in the intangible layer, but pushes scarcity down into the physical layer.

Every “free” unit of digital output demands a costly unit of energy and metal.

Economists don’t know how to model that because the spreadsheet category “software” was invented precisely to pretend it sits above physics.

That’s why abundance isn’t utopia.

It’s a structural break.

If the price of labour falls faster than the price of resources, the debt model disintegrates.

2.1.9 Why Pension Systems Fear Productivity

Debt economies need a future with prices, not a future with efficiencies.

Nothing terrifies a pension system more than a productivity miracle.

When labour is infinite, the meaning of money collapses.

This is the point where linear forecasting dies.

You can’t draw a straight line from 1995 to 2035 when one endpoint assumes scarcity forever, and the other assumes selective abundance.

The world stopped following graphs the moment the inputs became contradictory.

That is why every forecast model built in the last 50 years is fiction. Not dishonest—just obsolete.

2.2 — The Central Bank Mirage

How monetary policy replaced productivity without anyone saying it out loud

Monetary policy became the great improvisation of the late 20th century.

A tool designed for cyclical adjustment quietly evolved into the operating logic of the entire system.

Interest rates stopped being a price of capital. They became a substitute for productivity.

Whenever the real economy failed to produce growth, central banks produced the feeling of it.

In a world where consumption outpaced output, the key economic skill was not engineering or manufacturing.

It was timing the next cut.

This was not corruption. It was the rational adaptation of institutions to a structural slowdown they could not admit.

When productivity stalls and demographics invert, the old tools fail.

Rather than confess the curve had broken, policymakers discovered a workaround:

Financial expansion disguised as economic expansion.

The rate became a narrative instrument. The narrative became policy.

2.2.1 Monetary Policy as National Myth

After 1971, fiscal constraint dissolved, but belief remained.

The gold disappeared. The ritual stayed.

That required a new anchor, and it arrived quietly:

Central banks became the guarantors of everything that used to be defined by resources.

Growth was no longer tied to energy or productivity. It was tied to confidence.

And confidence could be managed.

A clever sentence at a press conference could move more “value” than an industrial breakthrough.

Governments discovered that managing expectations was a cheaper form of growth than building capacity.

A factory took ten years.

A rate cut took ten minutes.

The implications were profound:

The communications department became an economic actor.

2.2.2 The Rate-Cut Addiction Cycle

Every structural slowdown behaved like a recession. Every recession was treated like a temporary shock.

So the same tool was applied repeatedly:

Cut rates.

Stimulate demand with cheaper debt.

Inflate asset prices.

Households feel richer.

Consumption rises.

GDP registers “growth.”

Politicians call it “policy success.”

Nothing changed structurally. Something changed emotionally.

Debt replaced wages. Sentiment replaced productivity.

The loop was elegant because it worked for a very long time, and the costs accumulated in places economists don’t measure:

political expectations asset fragility the belief that growth is a right, not a consequence

2.2.3 QE as Emotional Management

Quantitative Easing was sold as liquidity provision.

In practice, it was emotional infrastructure.

A way to reassure markets that nothing truly bad could happen, because the central bank would materialise money out of policy statements.

QE created a new kind of political psychology:

Risk-free capitalism.

A game where profit was privatised and systemic failure was socialised via the central bank’s balance sheet.

The incentive was corrosive in a quiet way.

Once capital understood that downside was managed, it abandoned discipline.

Debt-financed buybacks replaced investment.

Valuation replaced innovation.

The stock market became a proxy for national confidence, so monetary policy became a tool to defend mood, not economics.

QE was not a conspiracy.

It was a civilisation-scale sedative—a way to avoid admitting that the productivity engine had stalled.

2.2.4 Asset Inflation Pretending to Be Prosperity

When income stagnates, asset inflation becomes the politically acceptable form of redistribution.

It is painless for governments and invisible to those who benefit from it.

House prices rise. Retirement statements rise. Stock portfolios rise.

A society that cannot increase wages can at least increase the number of digits in the brokerage app.

This created the illusion that the middle class was advancing.

When in reality, the price of the middle class was advancing.

Housing appreciation was not wealth creation.

It was a transfer from future buyers to current owners.

A nation got rich by making its children pay more.

Politicians celebrated the numbers without understanding the algebra.

2.2.5 The Hidden Violence of Soft Money

Soft money has a reputation for being humane.

It is the opposite.

Hard adjustments—restructuring, industrial planning, immigration reform, training—were avoided because the system had a cushion:

monetary expansion.

Every necessary reform was postponed because the central bank could buy time, and time appeared to be free.

But time financed with debt is not time.

It is a claim on future voters.

Soft money is violence by delay. The bill arrives, but the author is gone.

2.2.6 When the Model Runs on Belief

Every economic system requires something sacred:

gold oil land religion ideology

The modern West chose belief in the competence of its own institutions, especially the central bank.

This worked because belief is self-fulfilling—until it isn’t.

People assumed:

interest rates could always fall inflation could always be “managed” debt could always be refinanced consumption could always rise asset prices would always recover

The assumption became the architecture. Forecasting became a form of confirmation.

Economists built models where the future worked because the model required it.

Monetary policy—originally a tool—became the physics.

2.2.7 Why Inflation Came Back Like a Ghost Debt

Inflation did not return because of a single shock.

It returned because a soft-money equilibrium finally met a hard constraint:

supply was no longer global energy was no longer cheap labour was no longer scarce demographics were no longer hiding the arithmetic

When central banks expanded money faster than societies could expand capacity, prices rose.

Not temporarily. Mechanically.

For a generation, inflation had been hidden by:

globalisation cheap labour commodity arbitrage

The West was exporting its inflation into the wages of foreign workers and the minerals of foreign mines.

When those buffers broke, inflation returned to sender.

The ghost debt came home.

2.3 — The Mechanism Nobody Debated

How the West Replaced Productivity With Policy — Quietly, Accidentally, Permanently

No parliament voted for it.

No manifesto announced it.

No economist admitted it was happening.

Yet from 1980 to 2020, the West built the most powerful economic mechanism in modern history:

A system where every crisis justified more leverage, and every wave of leverage suppressed the very productivity the system claimed to pursue.

This wasn’t ideology. It wasn’t neoliberalism, monetarism, or supply-side metaphysics.

It was habit—engineered gradually through five administrations, each convinced it was responding to emergencies rather than rewriting the operating system.

The Mechanism: A Self-Reinforcing Loop

The mechanism works like this:

Use debt to solve a crisis.

Markets reward you for stabilising the present.

Future policymakers inherit a system more dependent on debt than before.

Repeat.

By the time anyone noticed, leverage wasn’t a tool. It was the economy.

Now—chapter by chapter—here is how the mechanism built itself.

2.3.1 Reagan–Volcker: The Birth of Leverage Politics

Volcker killed inflation the only way possible:

with interest rates brutal enough to crack stone.

Reagan revived the economy the only way politically viable:

with deficits large enough to drown the pain.

Together—unintentionally—they created leverage politics:

Monetary tightening caused a recession.

Fiscal expansion papered over the recession.

Markets learned the lesson:

Washington will always offset hardship with debt.

This was the birth of the doctrine no one named:

If the private sector can’t borrow, the state will do it for them.

It worked. It also rewired the incentive structure of democracy.

2.3.2 Clinton–Greenspan: Equity as Welfare

The 1990s were sold as the productivity miracle.

They were, in practice, the asset inflation miracle.

Clinton balanced the budget on paper.

Greenspan lowered rates whenever a sneeze hit the markets.

Wages stagnated. Equities soared.

Household wealth rose. Household savings collapsed.

This was the decade when policymakers quietly accepted a substitution that still defines the West:

If wages cannot rise, asset prices must.

Stocks became the welfare system of the middle class.

Housing became the pension.

Retirement became a bet on the S&P 500.

A society built on income turned into a society built on valuation.

2.3.3 Bush–Bernanke: Crises as Stimulus

9/11, China’s WTO shock, and the subprime bubble created the perfect storm.

Under Bush, deficit spending became patriotic.

Under Bernanke, the Federal Reserve discovered a new idea:

A crisis is an opportunity to expand the balance sheet.

This was the era when markets discovered a thrilling truth:

Downside risk had a floor.

Each intervention strengthened the addiction:

Cut rates → markets rise

Add liquidity → markets rise

Bail out → markets rise

Repeat → no consequences (yet)

Capitalism without bankruptcy. Democracy without austerity. Risk without punishment.

It felt like progress.

It was structural decay with good press coverage.

2.3.4 Obama–QE: Debt as Social Stability

Obama inherited the wreckage and had two choices:

Let the system reset—and take the political and social violence.

Stabilise everything—with debt, liquidity, and promises.

He chose stability. Any sane leader would have.

QE wasn’t stimulus. It was anaesthesia.

Cheap money propped up households, banks, pensions, and governments.

Inequality soared, but insolvency was postponed.

This is the moment leverage stopped being economic and became social.

Debt was no longer the means to growth. It became the price of avoiding revolt.

Once that line is crossed, you cannot return.

2.3.5 Trump–COVID: Printing the Feeling of Prosperity

Trump broke every fiscal norm Republicans claimed to believe in.

COVID finished the job.

For the first time since World War II:

every household was subsidised every business was subsidised every market was subsidised every government was subsidised

The US treated consumption like a human right.

Europe treated payroll like a national monument.

We printed the feeling of prosperity while the real economy was padlocked.

This was the moment Western citizens learned the most dangerous lesson:

Money is political fiction—and the fiction can always be extended.

A population that internalises this will never accept austerity again.

2.3.6 Biden–Inflation: The Return of Arithmetic

Biden did not cause the inflation.

He merely arrived at the moment the bill came due.

After forty years of leverage reflexes:

supply chains broke demographics tightened real capacity was scarce and the printed demand finally exceeded what the world could produce

Inflation was not an error.

It was the first honest price signal in a decade.

For the first time in forty years, arithmetic reappeared.

The mechanism that no one debated finally met a force that couldn’t be negotiated with:

Capacity.

And capacity cannot be conjured by legislation.

2.4 — Europe: The Elegant Wrong Turn

The only civilisation that consciously chose comfort over power—and now faces a world where power is the price of comfort.

Europe is history’s most civilised retreat.

A continent that, after tearing itself apart twice, made a deliberate decision to stop chasing power and start perfecting life.

It worked—spectacularly.

And that success is exactly why the bill is now due.

Europe didn’t decline because it was incompetent.

It declined because it chose to be harmless, and the world stopped rewarding harmlessness.

Europe built the most humane social model on the planet at the exact moment the rest of the world doubled down on industrial capacity, sovereign energy, and geopolitical leverage.

That divergence worked beautifully during the unipolar American era.

It works far less well in the bifurcated world emerging now.

2.4.1 Why Europe Didn’t Need Debt to Be Popular

America needs debt to make voters feel richer.

Europe never did.

Its legitimacy came from security, dignity, and predictability—not asset prices.

You didn’t need a booming stock market when you had universal healthcare.

You didn’t need wage inflation when rent controls and social insurance cushioned the edges of life.

Elections were won on continuity, not disruption.

But the political strength of this model is also its weakness:

It relies on a stable world with externalised security and cheap imported energy.

Once those conditions are removed, the mathematics stop working.

2.4.2 Welfare as Growth Substitution

Here is the truth Europe never admits:

Welfare replaced productivity.

Not consciously. Not maliciously. Just quietly, over decades.

Every time growth lagged, redistribution stepped in.

Every time industry declined, subsidies softened the blow.

Every time birth rates fell, the welfare state expanded to maintain the illusion of stability.

Europe didn’t solve growth. It socialised the symptoms of stagnation.

It’s a masterpiece of political engineering—but not an economic one.

2.4.3 German Exports Inside a Dollar World

Germany pulled off the neatest trick of the late 20th century:

Run an export empire without calling it an empire.

It did this because two miracles aligned:

American hegemony kept global shipping lanes open.

Russian energy kept German industry cheap.

A dollar world + a gas pipeline = Europe’s only true growth engine.

Washington tolerated neither indefinitely.

Because a Europe wired to Russian energy becomes a Europe outside American influence.

And that is the one thing US grand strategy has opposed since 1945.

Nord Stream wasn’t a pipeline. It was a geopolitical escape route.

Hence the “mysterious” explosions and the decades of American objections before they blew up.

Germany’s elegant model worked until it violated the architecture it relied on.

2.4.4 France: Philosophical Realism, Financial Faith

France understood the American system better than anyone.

And complained about it louder than anyone.

Yet depended on it more than anyone would admit.

The French instinct for strategic autonomy is real.

The French reliance on debt-funded comfort is equally real.

Paris talks like a sovereign power.

It budgets like a mid-tier province in the US dollar empire.

France’s tragedy is not arrogance.

It is ambition without the industrial base to fund it.

2.4.5 Italy & Spain: Debt Without Sovereignty

Southern Europe imported the American lifestyle without importing the American currency power.

The result?

A monetary union that lets you borrow like Washington but forces you to repay like Buenos Aires.

Italy and Spain didn’t misbehave.

They did exactly what democracies with ageing populations and no productivity growth always do:

They borrowed.

But unlike the US, they cannot print the currency they owe.

They outsourced their lender of last resort to Frankfurt—which means they outsourced political agency as well.

Debt is not the problem. Debt without sovereignty is.

2.4.6 Eastern Europe: Industrial Memory Meets Demographic Collapse

Eastern Europe remembers industry.

It remembers production, discipline, and hard power.

It has a strategic clarity Western Europe lost in its postmodern phase.

But it lacks the one ingredient strategy cannot replace:

young people.

The region is ageing faster than Japan.

It exports talent to Germany and Britain.

It imports automation because it cannot import workers.

Its instinct is realist, but its demography is terminal.

Eastern Europe could have been Europe’s industrial revival.

Instead, it is becoming Europe’s warning about the price of demographic neglect.

2.5 — China: The Mirror That Isn’t a Mirror

Yes, China has massive debt—but the system metabolised it into capacity, not consumption.

Western commentators obsess over the headline number:

“China’s debt-to-GDP is enormous!”

Correct. And irrelevant.

China’s debt is not Western debt. It plays a different role, serves a different purpose, and produces different outcomes.

The West borrows to extend demand.

China borrows to expand capacity.

That one distinction dissolves most of the confusion.

Debt is not dangerous because it is large.

Debt is dangerous when it finances nothing that makes you stronger.

China’s debt financed:

ports railways refineries shipyards EV supply chains steel complexes robotics clusters fabrication plants the largest industrial workforce in human history

In other words:

China borrowed against a future in which it would own the supply chain. And it does.

2.5.1 Why China’s Debt Looks Western but Isn’t

On paper, China’s debt looks like an American fever dream:

Local governments drowning in liabilities property developers over-levered shadow banks everywhere

But appearances mislead.

Most Western debt is consumption smoothing:

mortgages healthcare student loans tax-cut deficits financial engineering to inflate asset prices

Most Chinese debt is capacity building:

infrastructure manufacturing logistics industrial clusters technology parks

Western households borrow to feel richer.

Chinese administrations borrow to make the nation stronger.

One system borrows for today. The other borrows for tomorrow.

Which is why commentators who treat debt as a universal pathology misunderstand the operating system entirely.

2.5.2 LGFVs — Borrowing Against Future Factories

Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) are the West’s favourite punchline.

Usually by analysts who’ve never set foot in a Chinese industrial zone.

LGFVs are not primarily a bailout mechanism. They are a development engine.

They borrow today to build the industrial platform that will generate tax, jobs, exports, and geopolitical leverage tomorrow.

The LGFV system effectively says:

“We will build the factories first—the economic activity will arrive to fill them.”

In the West, this would be reckless.

In China, it works because:

the state controls land the state directs capital the state coordinates industry the state suppresses political backlash until outcomes materialise

An LGFV-financed industrial park may look like debt.

What it actually is: a forward contract on national capacity.

2.5.3 Debt as Industrial Weapon

China does not see debt as danger. It sees debt as leverage.

Debt is how China compresses time—building in ten years what took the West forty.

Debt is how China creates lock-in—tying foreign nations into Chinese-standard supply chains, ports, grids, and telecoms.

Debt is how China controls price—scaling production until competitors suffocate under margin pressure.

Debt is how China acquires bargaining power—because a nation that manufactures everything dictates terms to nations that manufacture little.

Debt is how China transforms strategic intent into physical infrastructure.

Western governments write strategy papers.

China erects steel, concrete, and semiconductor fabs.

2.5.4 The Export of Factories, Not Goods

The West still imagines China as the “world’s factory.”

That phase is already over.

China is now exporting factories, not just the goods that come out of them:

battery plants to Europe rail networks to Africa solar capacity to the Middle East shipyards to South Asia telecoms infrastructure everywhere

China is not chasing export markets. It is replicating its industrial system inside other civilisations.

This is how empires are built in the 21st century—not through conquest, but through capacity colonisation.

If you control the machines that make the machines, you control the future.

2.5.5 Demography: The Beginning of China’s Japan Moment

China does have one real problem: demography.

It is entering its Japan moment—but without Japan’s wealth, cohesion, or external security blanket.

The population is shrinking. The workforce is contracting. The age pyramid is inverting.

But China isn’t Japan.

Japan faced demographic decline after it had completed its industrial rise.

China faces demographic decline during the consolidation of its industrial empire.

The difference is structural:

Japan aged into a global system designed and guaranteed by the US.

China is ageing into a world where it must build the system itself.

But this also creates the strategic pivot:

China has no choice but to automate—aggressively.

Demography forces China deeper into robotics, deeper into AI, deeper into synthetic labour.

Which leads directly to the final point.

2.5.6 Why Synthetic Labour Came at the Perfect Time

AI and robotics arrived at the exact moment China needed them.

Not as luxury, but as survival mechanism.

A shrinking workforce is a crisis for a consumption economy.

It is less of a crisis for a production economy that can replace labour with machines.

China’s demographic cliff accelerates its automation curve.

It becomes the first civilisation where synthetic labour is not optional.

It is the only way to maintain capacity sovereignty.

While the West debates UBI and ethics boards, China integrates:

humanoid robots into logistics AI systems into manufacturing lines automated ports autonomous mining self-optimising supply chains

This is not technological enthusiasm. This is industrial necessity.

China will be the first nation to run a near-post-labour industrial economy at continental scale—not because it is visionary, but because the alternative is collapse.

2.6 — The Great Political Constraint

No democracy can run an honest productivity campaign after two generations of leverage politics.

Every Western democracy now lives inside the same contradiction:

The economy requires long-term investment. The electorate demands short-term relief.

For forty years, politicians solved this by using debt as a lubricant—smoothing every shock, funding every promise, bending every curve.

It worked beautifully, right up until the system needed real productivity rather than financial sedatives.

Now the bill arrives. And democracies have no mechanism to pay it.

Re-industrialisation requires sacrifice.

Voters require comfort.

Those two lines do not intersect.

2.6.1 The Voter Time Horizon Problem

Democracies are built on four-year cycles.

Industries are built on forty-year cycles.

Productivity comes from:

new ports new energy grids new industrial clusters new training pipelines new supply chains

None of these produce results within a single electoral term.

Most don’t even break ground in time for a re-election speech.

Voters punish delayed gratification.

Politicians respond by avoiding it altogether.

A democracy facing structural decline behaves exactly like a household living month-to-month:

Anything beyond the next bill is someone else’s problem.

2.6.2 Short Elections vs Long Investments

No politician is rewarded for telling voters that:

energy will cost more before it costs less wages will fall before industry recovers consumption must be restrained to rebuild supply imports must be reduced to restart domestic capability deficits must shrink before investment can expand

These are all true statements.

They are also electoral suicide.

So democracies default to the only politically safe strategy:

Borrow, subsidise, postpone. Let the next government handle the consequences.

The result is predictable:

Industrial policy becomes branding, not construction.

Announcements outpace achievements by a factor of ten.

“Green transitions”, “industrial acts”, “net-zero manufacturing”—all slogans written for voters, not for factories.

2.6.3 Industry Requires Pain Before Prosperity — Politics Requires Prosperity Before Pain

Every real industrial campaign in history required a phase of national discomfort:

Britain’s enclosures America’s rail build-out Germany’s reunification shock Korea’s forced savings model China’s hukou system and industrial migration

The pattern is constant:

Industry requires sacrifice before strength. Democracy requires strength before sacrifice.

Which is why no Western democracy can run a genuine productivity programme:

Investment hurts first. Prosperity comes later. Elections come in-between.

To choose industry, a government must ask voters to endure a period where things get worse.

No one running for office volunteers for that.

2.6.4 The Iron Law of Retirement Voting

The West is now ruled—numerically, structurally, and politically—by the retired.

Older voters decide elections.

Older voters own most of the assets.

Older voters rely on transfers funded by the shrinking young.

This creates the iron law:

Pension security > National productivity.

Any policy that risks:

house prices bond values welfare payments healthcare promises

…is dead on arrival.

Industrial strategy becomes secondary to the maintenance of asset stability—which is precisely the opposite of what re-industrialisation requires.

A nation where the majority of voters no longer work cannot prioritise work.

2.6.5 No Mandate for Reality

The core problem is not ideology. It is legitimacy.

No democratic leader today has a mandate to say:

“Consumption must fall.”

“Energy prices must rise temporarily.”

“Savings must increase.”

“Imports must decline.”

“Debt must shrink.”

“We must build factories before we subsidise lifestyles.”

Every statement above is true.

Every statement above would end a political career.

Democracies can administer comfort. They cannot administer discipline.

Which is why, when the debt–productivity break arrives, democracies reach for the only tools they still control:

messaging financial engineering short-term subsidies political theatre the language of reassurance

Arithmetic is replaced by narrative because narrative is the only thing voters accept.

But nature is not a voter. And reality does not negotiate.

2.7 — The Terminology of Denial

Once the maths stopped working, the language evolved to hide it.

Economics didn’t fail quickly. It failed politely.

When the debt–productivity relationship snapped, nobody announced a paradigm shift.

They updated the vocabulary.

Every time the system produced a result that contradicted the model, economists didn’t revise the model.

They invented a new phrase to preserve it.

This is not conspiracy. It is institutional psychology.

When reality becomes awkward, technocracy develops euphemisms.

Below is the dictionary of denial that carried the West through the last decade of the debt cycle.

2.7.1 “Secular Stagnation”

The first great euphemism.

It sounds profound, almost geological.

In practice it means:

“Growth is dead, but we’d prefer not to say that.”

Rather than admit that productivity had flatlined because investment was hollowed out, industry offshored, and demographics turned, economists framed it as a mysterious long shadow falling over the economy.

It was a riddle, not a diagnosis—which made it very convenient.

If stagnation is “secular”, nobody is to blame.

If stagnation is structural, someone might ask where the structure broke.

2.7.2 “Temporary Disinflation”

Used every time inflation fell for reasons that had nothing to do with policy.

Cheap Chinese goods? Temporary disinflation.

Demographics reducing demand? Temporary disinflation.

Technology lowering marginal costs? Temporary disinflation.

In reality, these were permanent downward forces on prices, masking the inflation that should have appeared from ever-expanding debt.

But calling them “temporary” allowed central banks to behave as if the low-inflation environment was a natural gift rather than an imported subsidy from global supply chains.

When inflation finally returned in 2021–2022, the same voices declared it “transitory”.

They simply recycled the euphemism.

2.7.3 “Lower Neutral Rates”

This phrase did more damage than almost any other.

The “neutral rate”—the interest rate at which the economy is neither stimulated nor slowed—became a theological concept.

Each year, when growth underperformed, economists simply lowered the imaginary number.

What they were really admitting was:

“The system now collapses unless money is nearly free.”

But written in a way that made it sound analytical rather than existential.

Lower neutral rates became the intellectual justification for a world in which debt was the only functioning growth engine.

Once rates reached zero, rather than rethink the model, central banks drove them below zero and declared it an innovation.

Europe in particular embraced this fiction with gusto—because the alternative was to admit that its growth model had stopped producing growth.

2.7.4 “Soft Landing”

A phrase invented for politicians who need hope, and economists who need grants.

Every tightening cycle ended with someone promising that this time would be different.

That a decade of free money could be unwound without consequences.

That imbalances could normalise themselves gently.

That the business cycle could be tamed by rhetoric.

A soft landing is the macroeconomic version of telling a child the dog went to live on a farm.

It became doctrine because the alternative—recession, deleveraging, asset repricing—was too ugly to contemplate in systems held together by credit-based prosperity.

The phrase kept returning because it performed a psychological function:

“Please don’t panic.”

2.7.5 “Output Gap”

A technical phrase that did heroic work.

When an economy underperformed, the models didn’t say “the economy is weaker than we thought”.

They said “there is an output gap”.

This implied that the potential was still there—the economy was simply choosing not to express it.

It kept policymakers in the realm of the fixable.

If there’s a gap, you can close it.

If the potential is illusory, the entire forecasting framework dissolves.

The output gap hid the obvious:

Potential output wasn’t falling temporarily—the demographics that produced it were disappearing.

2.7.6 “Resilience”

The final euphemism—and the most ironic.

“Resilience” became the elite way of saying:

“The system hasn’t collapsed yet, therefore everything must be fine.”

It ignored the reason the system hadn’t collapsed:

ultra-low rates perpetual deficits imported disinflation asset inflation papering over real economic weakness

Every wobble was met with stimulus.

Every crisis was met with liquidity.

Every contradiction was met with narrative.

The system looked resilient because it was being kept alive by interventions so large they became invisible.

Calling that “resilience” is like calling an ICU patient “energetic” because the machines are still on.

2.8 — The Break Becomes Visible

2025–2030 is when the illusion finally stops working.

For forty years, the system could hide its contradictions behind demographics, disinflation, and debt.

By the late 2020s, all three crutches splinter at once.

The break isn’t a crash.

It’s worse.

It’s clarity.

A moment when even the most well-trained optimist can no longer pretend that the old model is merely “under strain”.

This is when the contradictions stop being cyclical—and start being structural.

Below are the five signals that make the break undeniable.

2.8.1 Negative Debt Returns as Structural Reality

The final mask falls here.

For decades, debt provided diminishing returns.

By the second half of the 2020s, the returns turn negative.

Meaning:

Each new dollar of borrowing subtracts from future growth rather than adds to it.

Not temporarily. Not during a crisis. Structurally.

The mechanism is brutally simple:

Interest bills rise faster than GDP.

Taxes flatten because the working-age population shrinks.

Investment doesn’t respond to cheap money because firms have no labour to scale.

The debt trap closes.

2.8.2 Productivity Growth Without Wage Growth

AI and automation deliver the productivity miracle everyone promised.

But wages stagnate, because labour is abundant.

The system breaks here.

Productivity was supposed to justify leverage—the idea that borrowing today would be repaid by tomorrow’s higher output.

But if output rises while labour becomes cheap, then the debt cannot be serviced by wage income.

It can only be serviced by asset inflation.

And asset inflation requires new borrowing.

Which requires productivity.

Which requires more labour displacement.

Which requires more asset inflation.

The loop tightens until it snaps.

2.8.3 Labour Decouples from Pricing

For 200 years, labour was the primary input to value creation.

When labour became abundant (or unnecessary), the entire pricing architecture broke.

You cannot model an economy where:

labour is abundant energy is scarce capital is abundant materials are scarce

Using models built for the opposite world.

The price system stops transmitting information. It starts transmitting noise.

2.8.4 Monetary Policy Loses Its Weapons

Central banks can cut rates to zero. They can print money. They can buy assets.

But they cannot:

create young workers build factories restore supply chains increase energy capacity manufacture political consensus

By the late 2020s, every tool central banks possess has been exhausted.

Rates are already negative in real terms.

Balance sheets are already massive.

Stimulus has already been applied.

And the structural problems remain.

At this point, monetary policy becomes theatre—and everyone knows it.

2.8.5 Capitalism’s Scarcity Engine Stalls

Capitalism requires scarcity to function.

Scarcity creates prices. Prices create incentives. Incentives create production.

But AI creates selective abundance (labour) while intensifying scarcity (energy, materials, cooling).

You cannot run a price system on contradictions.

The engine stalls.

2.9 — The Choice Nobody Wants to Make

Shrink or go vertical.

Everything else is décor.

The menu is brutally short.

The models don’t work. The cushions are gone. The political stories that kept the lights on have stopped persuading anyone under 40.

Every government now performs the same choreography:

promise growth without explaining where it comes from subsidise voters without admitting the subsidy is debt gesture vaguely at “innovation” as if a slightly better app will fix a civilisation-scale energy and productivity problem

But underneath the theatre sits a choice so stark that no manifesto, academic panel, or central bank speech will state it plainly:

Either economies shrink, or industry moves off Earth.

Everything else is décor.

2.9.1 Degrowth as Moral Sermon, Not Industrial Strategy

Degrowth has become the polite fantasy of people who think economics is a moral narrative rather than a physical system.

It is framed as wisdom: consume less, live simply, share more.

It is sold as virtue: a nobler way to live on a finite planet.

But degrowth is not a strategy. It is a sermon.

It works beautifully in essays and disastrously in spreadsheets.

No industrial nation has ever voluntarily shrunk and remained politically stable.

You can downshift a household. You cannot downshift a civilisation without breaking its debt system, its pension system, and its political system.

Degrowth assumes that voters, having been trained for 50 years to expect rising living standards funded by leverage, will now embrace lower living standards in the name of planetary ethics.

They won’t.

And politicians know it.

2.9.2 Redistribution Inside a Shrinking Pie

When growth stalls, redistribution becomes the only tool left.

But redistribution without growth is civil war by spreadsheet.

You are no longer dividing the upside. You are dividing the disappointment.

And disappointment is partisan.

Left and right both converge on the same dead end:

The left proposes taxing wealth that only exists because the system inflated assets.

The right proposes cutting services that only exist because the system borrowed to provide them.

Both can win arguments. Neither can win arithmetic.

The problem isn’t inequality—it’s the size of the pie.

And no amount of rearrangement fixes a contraction.

2.9.3 The Thermodynamic Limit of On-Planet Compute

AI exposes the physical ceiling more brutally than any economist ever dared.

Training frontier models already pushes the limits of:

cooling water availability grid capacity usable land energy density

AI is not “virtual”. It is a thermodynamic sport.

Every improvement in intelligence requires more energy turned into less heat in less space.

You cannot scale compute another order of magnitude with on-planet constraints unless you are willing to:

carpet continents with data centres divert rivers for cooling build nuclear at an unprecedented pace bulldoze every vote-holding NIMBY in the process

It is not politically plausible, and soon it won’t be physically plausible.

The Earth is a wonderful place to live.

It is a terrible place to run a hyper-intelligent industrial system.

2.9.4 NIMBY as Civilisational Constraint

NIMBY was once a planning nuisance.

It is now a governing principle.

Try building:

a nuclear plant a high-voltage transmission corridor a desalination facility a gigafactory a major port or anything taller than a church spire

…on territory where citizens vote.

Modern democracy has made industrial expansion socially unacceptable and logistically impossible.

NIMBY began as neighbourhood sentiment.

It ends as a civilisational limit.

The irony is exquisite:

A system built on abundance now cannot build the tools required to generate more of it.

2.9.5 Why the Only Remaining Frontier Is Upward

By elimination, not aspiration, the frontier becomes obvious:

Space has no voters.

Space has no NIMBY.

Space has cold vacuum for free cooling.

Space has unfiltered solar flux.

Space has scale—industrial scale—without political constraint.

The vertical frontier is not utopian. It is thermodynamic.

The shift is not ideological but architectural:

Earth becomes residential, political, cultural. Orbit becomes industrial, computational, energetic.

This is the bifurcation the book prepares for:

A world where horizontal expansion is finished and vertical expansion is the only mathematically coherent path left.

Shrink, or go vertical.

Civilisations that refuse to choose will discover that physics chooses for them.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek