Part 3: The Vertical Economy. The vertical turn isn't ideology. It's thermodynamics.

Cost curves, industrial arithmetic, and why the next frontier is upward

📑 CONTENTS — PART III

THE VERTICAL ECONOMY BEGINS

3.0 — The Industrial Logic of Space

Why verticalisation is an economic inevitability, not a technological fantasy.

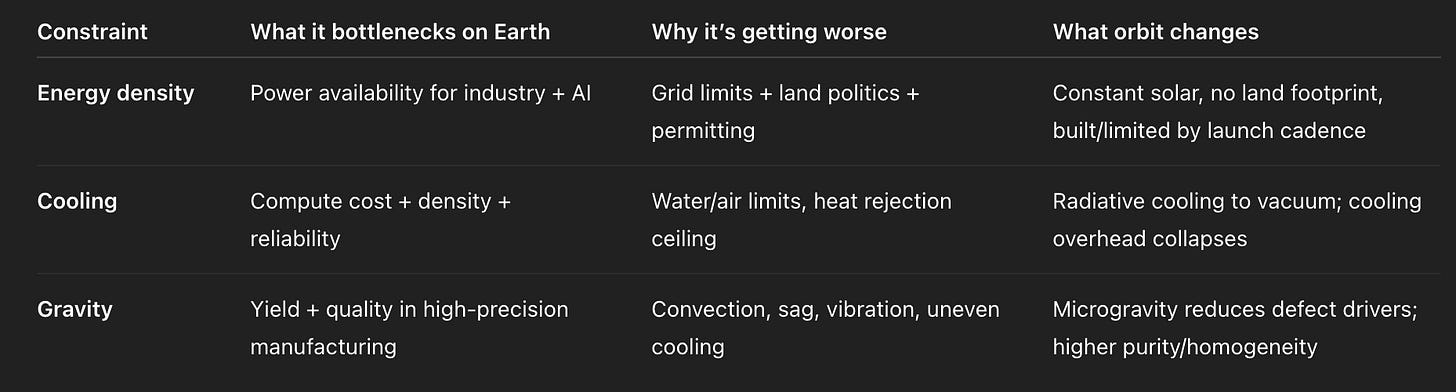

The three physical constraints: energy density, cooling, gravity.

The core claim: vertical industry begins the moment orbital cost < terrestrial cost for energy, compute, or manufacturing.

3.1 — The Cost-Crossover Equation

The chapter that fixes the gap in ALL space-economy writing.

3.1.1 Launch Cost Decline (2010–2040)

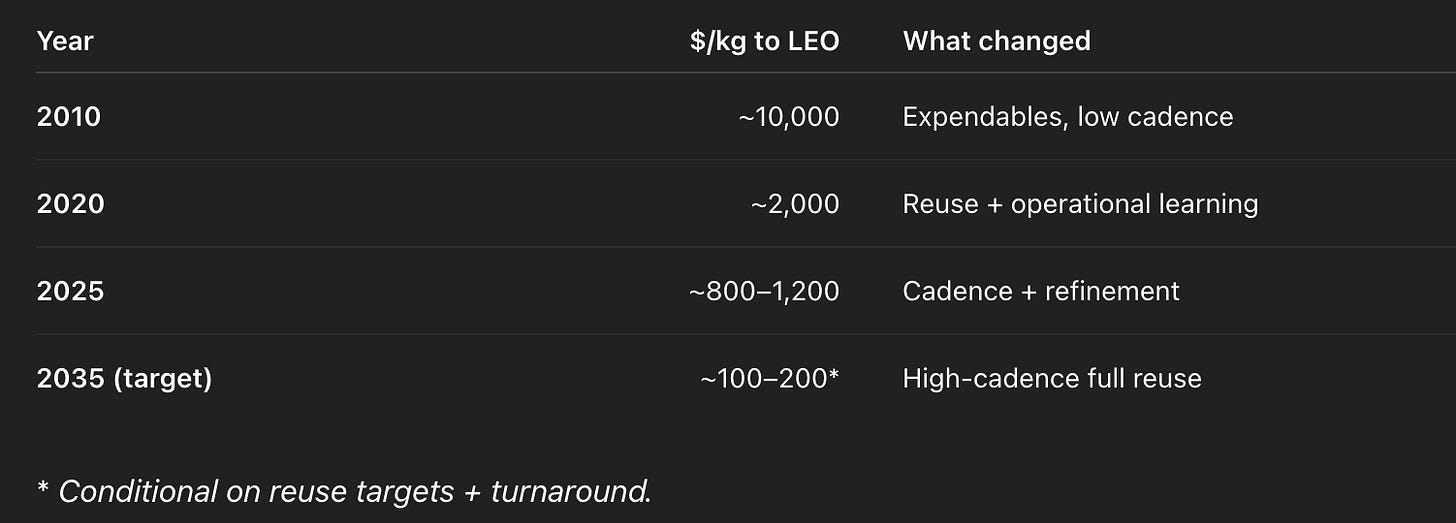

Explicit milestones:

2010: $10,000/kg →

2020: ~$2,000/kg →

2025: ~$800–1,200/kg →

2035 (target): $100–200/kg with high-cadence reuse.3.1.2 Earth vs Orbit: Cost Structure Comparison

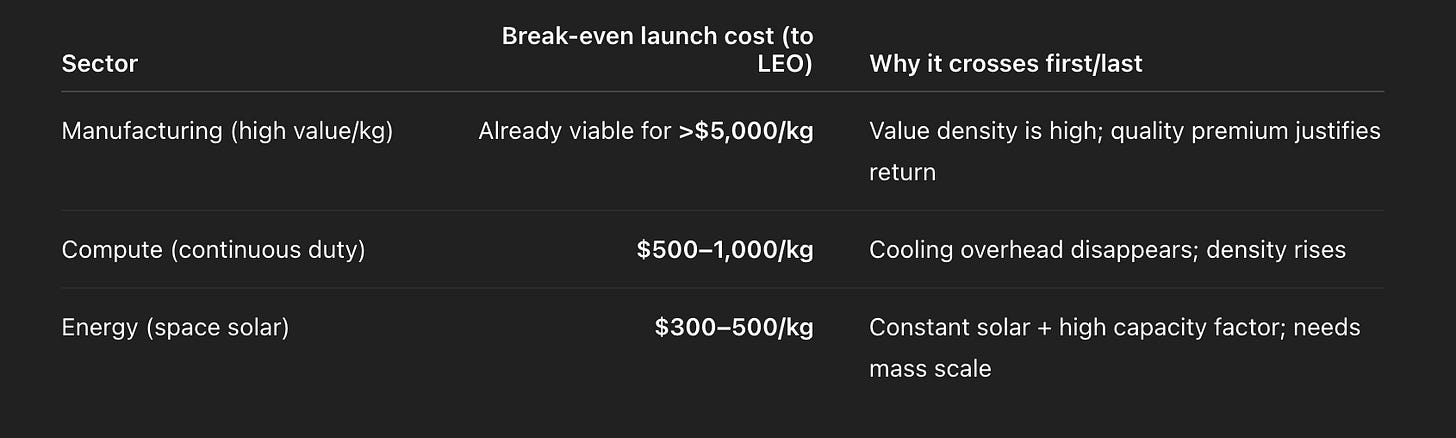

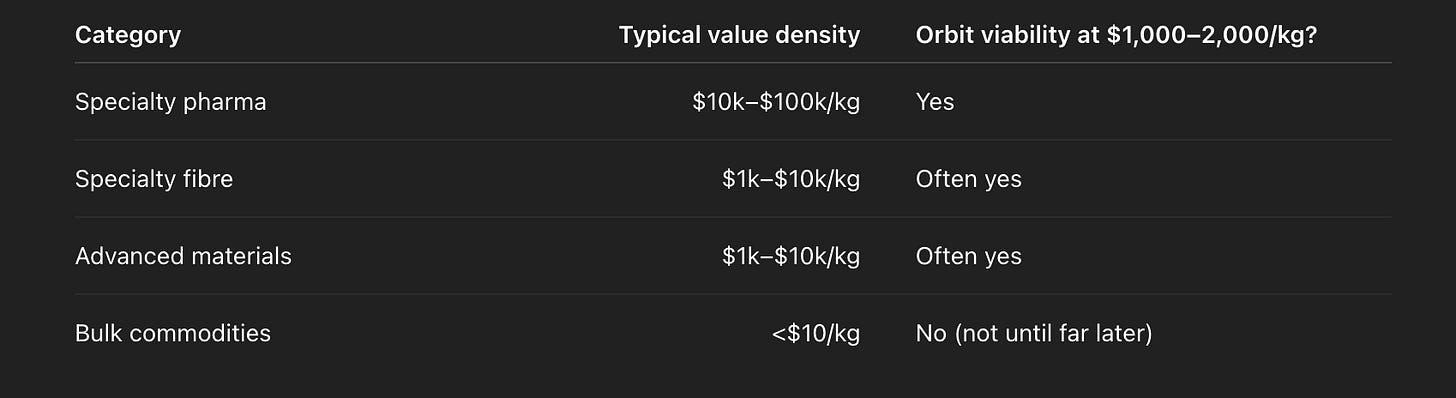

3.1.3 Sector Break-Evens

Energy crossover: $300–500/kg

Compute crossover: $500–1,000/kg

Manufacturing crossover: already viable for >$5,000/kg materials

3.1.4 Why 2035–2045 is the decisive decade

3.1.5 The new economic law: “Mass is cost; orbit is yield.”

3.2 — Compute in Vacuum: Zero-Cooling Economics

3.2.1 Radiative Cooling vs Terrestrial Cooling (0% vs 30–40% of power)

3.2.2 Heat Dissipation Constraints → Compute Density Explosion

3.2.3 Cosmic Rays, Shielding, Radiation-Hardened Chips

3.2.4 From Earth DCs to Orbital Compute Clusters

3.2.5 Cost model: Earth inference vs orbital inference (tokens per kWh)

3.2.6 Why AI pushes compute off-planet first

3.3 — Energy Above the Atmosphere

3.3.1 Constant Solar: 1,360 W/m², no atmosphere, no night

3.3.2 Orbital LCOE Modelling: $5–10/MWh equivalent

3.3.3 Terrestrial LCOE Saturation & Grid Limits

3.3.4 Microwave/Laser Transmission Losses (5–10%)

3.3.5 The geopolitics of “energy with no land footprint”

3.3.6 Earth’s energy ceiling vs orbital energy ceiling

3.4 — Manufacturing Where Gravity Is Optional

3.4.1 Semiconductor Yields in Microgravity

3.4.2 ZBLAN Fibre, Protein Crystals, Alloy Homogeneity

3.4.3 Value-per-Kilogram Logic

3.4.4 Earth’s structural constraints (weight, vibration, heat)

3.4.5 The physics of quality → why orbit makes better matter

3.4.6 The first €1 billion orbital factory (what it actually makes)

3.5 — Logistics Between Earth and Orbit

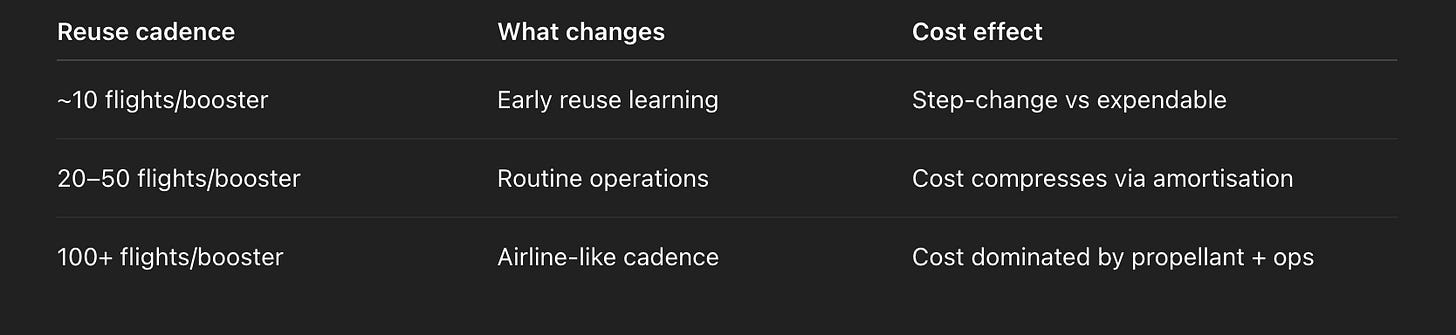

3.5.1 The Reuse Curve: 10 flights → 50 → 500

3.5.2 Propellant Depots + In-Space Refuelling

3.5.3 Cislunar Transfer Costs

3.5.4 Starship-Class Economics ($10m per launch → $200/kg delivered)

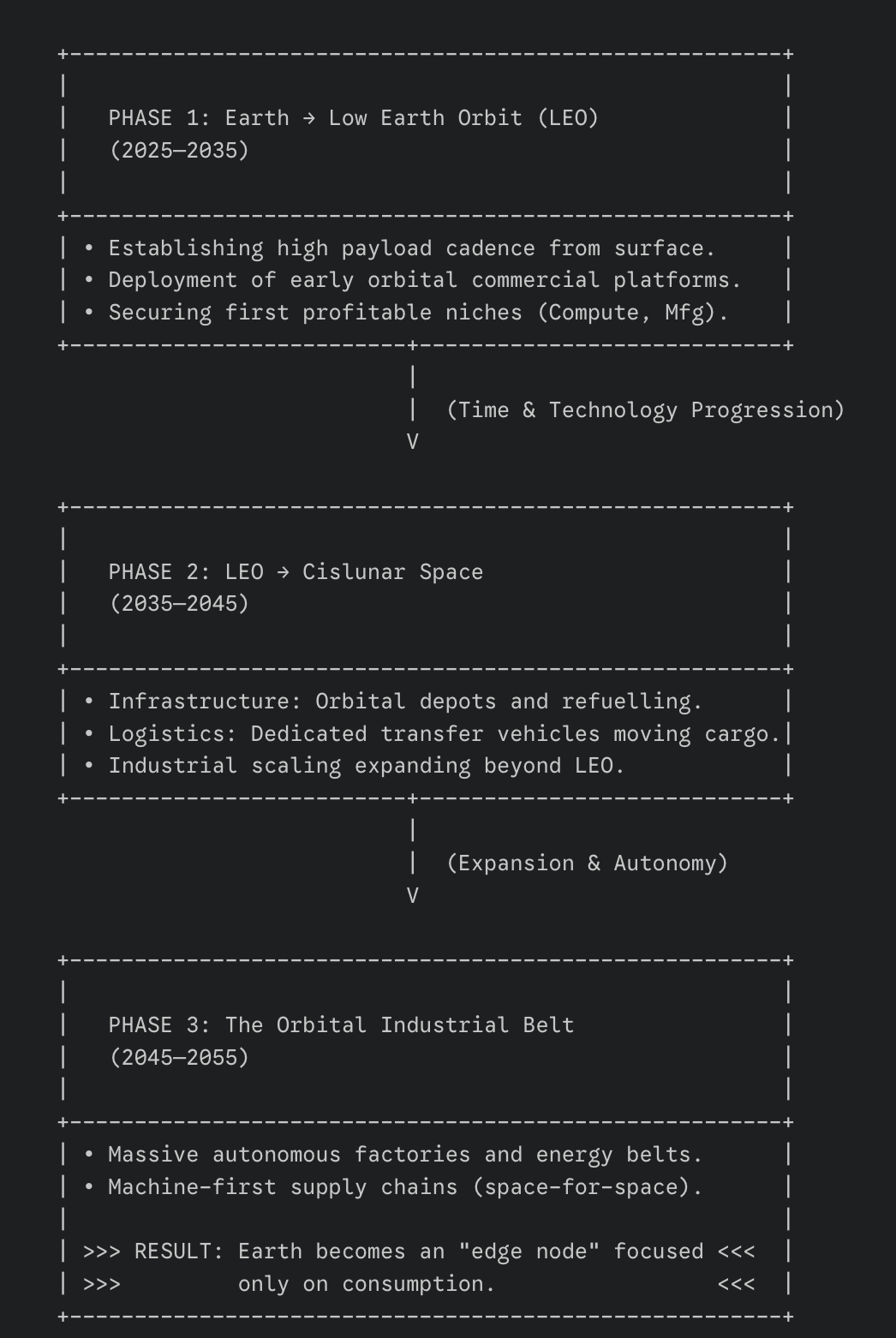

3.5.5 Industrial Phases:

Phase 1 (2025–2035): Earth → LEO

Phase 2 (2035–2045): LEO → Cislunar Infrastructure

Phase 3 (2045–2055): Orbital Industrial Belt3.5.6 Insurance, risk curves, and actuarial pricing of off-world supply chains

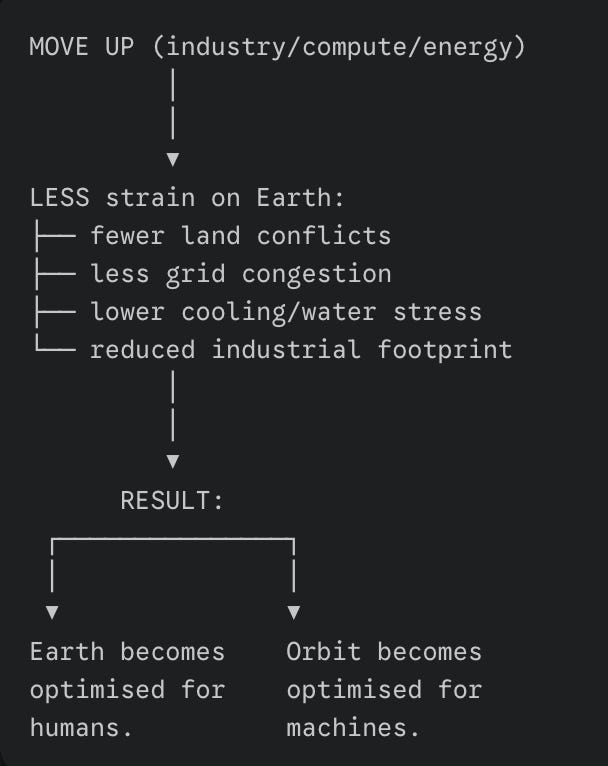

3.6 — The Earth–Orbit Split

3.6.1 Earth as Residential, Political & Agricultural Zone

3.6.2 Orbit as Industrial, Energetic & Computational Zone

3.6.3 The bifurcation of labour, capital, and machine agency

3.6.4 Sovereign AI & the fight for off-world compute

3.6.5 Why the vertical economy does NOT replace Earth — it frees it

3.0 — The Industrial Logic of Space

Why verticalisation is not a dream of technologists, but the next step in capitalism’s geometry.

For fifty years, the global economy expanded horizontally: more trade routes, more credit, more labour offshoring, more container ships, more data centres, more industrial parks carved out of land that was politically cheap. It worked because the world still had physical slack—land, labour, energy, and water that hadn’t yet been monetised.

We have now run out of slack.

This isn’t ideology; it’s physics wearing an economic mask. Every major constraint facing the modern economy has the same underlying shape: a system designed for expansion trapped inside finite boundaries.

Three boundaries, in particular, have stopped budging:

Energy density. Cooling. Gravity.

They sound abstract. They are not. They are the silent choke points that determine the cost of everything from AI inference to steel output to fertiliser to pharmaceutical production.

When those constraints hit, you have two options:

Shrink your ambition, or Find a zone where the constraints don’t apply.

Shrink, or go vertical.

The reason space has re-entered serious economic debate is not Elon Musk, NASA nostalgia or billionaire cosplay. It is because space is the only environment where the three load-bearing constraints of Earth-based industry disappear at the same time.

Not reduced. Not mitigated. Eliminated.

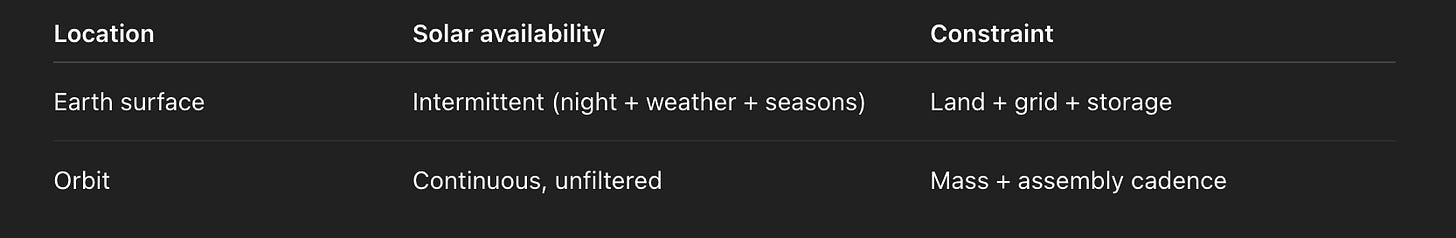

3.0.1 Energy: Earth Is Full — Orbit Isn’t

Every nation now competes over the same static landmass of solar and wind that must coexist with voters, farms, cities, and environmental law. Even if you approve new energy projects, the grid can’t absorb them fast enough. The bottleneck has shifted from generation to distribution.

Orbit doesn’t have this problem.

Outside the atmosphere, sunlight is constant—no clouds, no seasons, no night.

1,360 W/m² every second of every day.

No land rights, no NIMBY, no planning inquiries, no cables crossing contested farmland.

It is not idealism. It is geometry.

On Earth, adding 10 GW of solar can take a decade. In orbit, it is a deployment problem: launch mass and assembly cadence.

When AI drives global electricity demand into the tens of thousands of new terawatt-hours, policymakers will rediscover a basic equation:

Energy abundance requires land. Land is political. Orbit is not.

3.0.2 Cooling: AI Breaks the Thermodynamic Budget

Half the cost of a hyperscale data centre is simply heat management. Cooling is the unpaid tax of computation—the reason why AI inference, even in 2030, remains bottlenecked by the physics of air, water, and concrete.

In orbit, cooling is not a cost line.

Cooling is the environment.

A computer in vacuum radiates heat directly into space.

No chillers. No water towers. No heat sinks the size of apartment blocks.

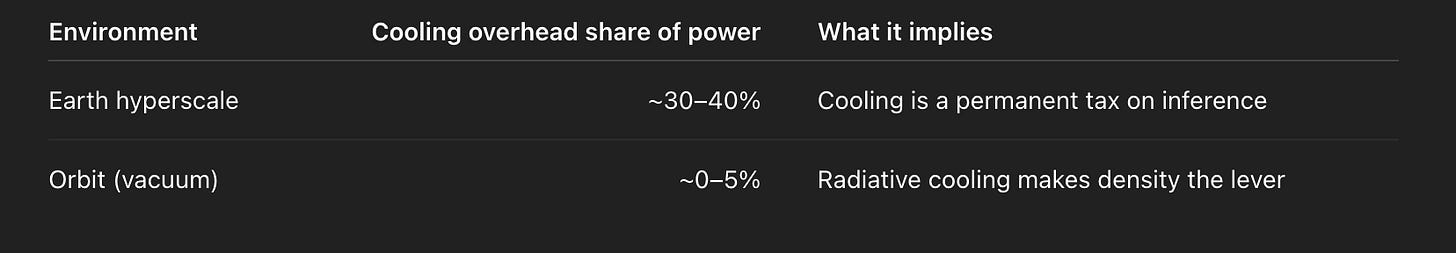

On Earth, cooling consumes 30–40% of the electricity input to large compute clusters. Above the atmosphere, that drops to near 0%.

This is why the first businesses forced off-planet will not be space hotels or asteroid miners. It will be the one sector where cost is dominated by thermodynamics:

AI.

Once the cost of cooling overtakes the cost of compute—a threshold we reach this decade—the economic centre of gravity shifts upward.

3.0.3 Gravity: The Hidden Enemy of Modern Manufacturing

Gravity is invisible until you design around it. Every factory on Earth assumes a single constraint: things fall down.

This matters more than most people realise:

Alloys cool unevenly. Semiconductors suffer defects from convection currents. Biological materials collapse under their own weight. Crystals grow imperfectly. Fibre optics sag microscopically, reducing quality.

In microgravity, you get perfect symmetry.

Perfect cooling. Perfect growth. Perfect homogeneity.

It is not that orbit is magically productive. It is that Earth is quietly wasteful.

The first trillion-dollar orbital industries will not be “new.” They will be existing industries done better: chips, fibres, crystals, pharmaceuticals. The value-per-kilogram is already high enough. The only missing variable is launch cost.

And launch cost is falling like a stone thrown off a skyscraper.

3.0.4 The Real Reason Space Becomes Industrial: Earth Has Become Uninvestable

Not uninvestable in the financial sense—uninvestable in the physical sense.

Try building:

a new nuclear plant in France, a hyperscale data centre in Germany, a lithium refinery in Spain, a gigawatt wind corridor in the UK, or a semiconductor fab in the Netherlands.

You won’t get protested—you’ll get litigated into geological timeframes.

The contradiction is simple:

The modern economy requires more energy, more compute, more manufacturing—but the modern voter will not allow the physical footprint of any of them.

NIMBY isn’t a political quirk. It is a civilisational constraint.

Orbit, by contrast, is governed by physics and cost curves, not municipal hearings.

Once the cost per kilogram drops below the terrestrial cost of regulation, the capital markets go vertical.

And they won’t come back.

3.0.5 The Core Claim of This Book

Everything before now—debt, demographics, AI, Europe, China, scarcity—sets up a single structural conclusion:

Capitalism cannot scale another order of magnitude on a planet where every square kilometre is owned, contested, regulated, inhabited, and ecologically brittle.

The horizontal map is complete.

The scarcity engine is faltering.

AI requires orders of magnitude more energy and compute than Earth can politically or physically absorb.

So the next industrial revolution does not happen on Earth.

It happens around it.

3.0.6 Why This Is Not Sci-Fi

Science fiction imagines futures that require new physics.

The vertical economy requires no new physics at all:

Launch costs falling to $100–200/kg (conditional on reuse targets) Modular orbital infrastructure Radiative cooling already possible Continuous solar already proven Microgravity manufacturing already demonstrated AI-driven automation reducing labour needs in orbit

The only missing component has been cost, not technology.

The moment cost crosses the threshold—and it will—economics takes over.

Capital flows where constraints aren’t.

Earth is all constraints.

Orbit is all opportunity.

This is the hinge.

3.0.7 The Sixty-Year False Start: Why This Time Is Different

Before dismissing this as another space dream, you need to understand why the last six decades of space promises failed—and why the structural conditions have now changed.

The Pattern of Broken Promises

O’Neill colonies (1975): Promised self-sustaining orbital habitats by 1985. Never happened.

Space tourism (1990s): Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin promised routine commercial spaceflight. Still waiting.

Asteroid mining (2012): Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries promised trillion-dollar resources. Both defunct.

Space manufacturing (2000s): Microgravity promised revolutionary materials. Remained a niche curiosity.

Each wave of space enthusiasm followed the same arc: visionary promise, venture capital enthusiasm, technical demonstration, then—silence. The reason wasn’t engineering failure. It was economic failure. The cost structure never improved enough to justify the business case.

What’s Structurally Different Now

Three things have changed:

1. Demonstrated Reuse, Not Theoretical

Previous space economics assumed expendable rockets. Falcon 9 has now completed over 300 landings. Starship is in active testing. This is not a promise. It is an observable fact.

The cost curve is no longer theoretical. It is empirical.

2. Cost Already Fallen 10x

In 2010, SpaceX charged $65 million per Falcon 9 launch (~$10,000/kg to LEO).

By 2024, that had fallen to $2,700/kg.

By 2025, with high-cadence operations, approaching $1,200/kg.

This is not a forecast. This is a trajectory.

3. Private Capital Replacing Cost-Plus

The old space industry was government-funded cost-plus: NASA and ESA paid whatever it cost, plus profit. There was no incentive to reduce cost.

SpaceX operates on private capital and margin pressure. Every launch that doesn’t land successfully is a loss. Every improvement in turnaround time is profit. The incentive structure is inverted.

4. Cadence in Days, Not Years

Falcon 9 launches roughly every 3–4 days. Starship is targeting 3–5 launches per day within 5 years.

Historical space programmes launched once per year, if that.

Cadence is the hidden variable in cost reduction. You cannot iterate your way to efficiency if you fly once annually.

5. Capital Markets Are Already Pricing This In

SpaceX is valued above Boeing and Lockheed Martin combined. Starlink has 6+ million subscribers and $8+ billion in annual revenue. Axiom Space is building commercial space stations. Varda is manufacturing in orbit.

This is not speculation. This is capital allocation in real time.

The difference between 2012 and 2025 is not that space became possible. It is that space became profitable. And once that happens, the trajectory is irreversible.

3.0.8 Summary: The System Hits the Ceiling, So It Builds a New One

By the end of Part II, the reader understands why the horizontal system broke.

Part III now explains where the vertical system begins—in the zone where physics becomes cheaper than politics.

The vertical economy is not a bet on rockets.

It is a bet on:

energy without land, compute without cooling, manufacturing without gravity, expansion without territory, industrial growth without voters.

It is the return of growth in a world that has run out of room for it.

And it starts the moment orbit becomes cheaper than Earth.

3.1 — The Cost-Crossover Equation

The moment orbit becomes cheaper than Earth—and why that moment arrives sooner than any government is prepared for.

Every industrial revolution has a single hinge: the moment a new environment becomes cheaper than the old one.

Coal beat wood. Oil beat coal. Containerisation beat break-bulk. Cloud beat server racks. Asia beat Detroit.

Capital never chooses ideology. It chooses cost curves.

Space will not become an industrial basin because CEOs develop a sense of cosmic destiny or because astronauts are photogenic. It will become one because, sometime between 2032 and 2042, the cost of producing a marginal unit of energy, compute, or high-purity material in orbit becomes lower than doing so on Earth.

And once that happens, the move is irreversible.

Industry follows the cheapest physics.

This chapter defines the crossover.

3.1.1 What Cost Crossover Actually Means

“Cheaper” is not sentimental. It is an engineering ledger.

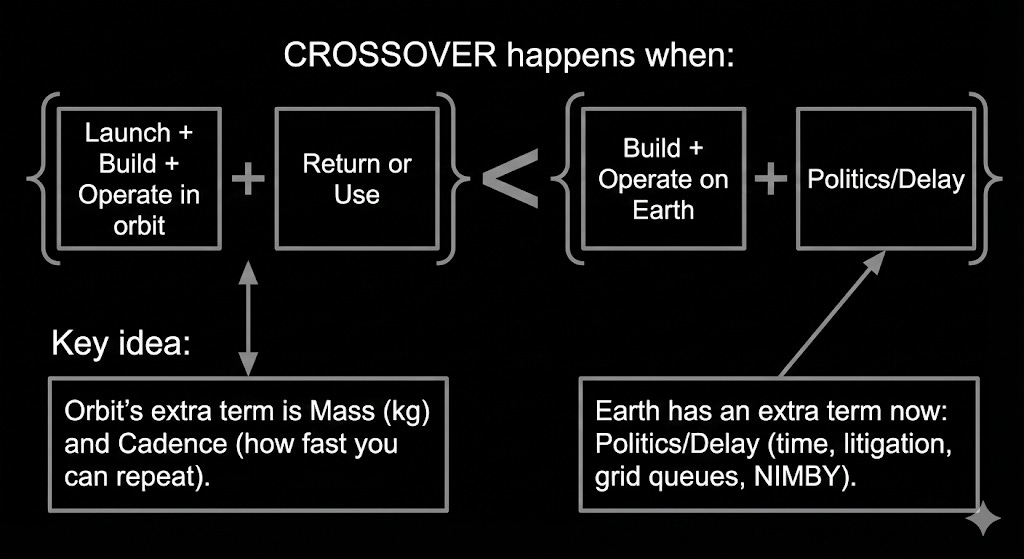

The crossover happens when:

(Cost of producing X in orbit) + (Cost of returning X to Earth or using it in orbit) < (Cost of producing X on Earth)

This is not a single number. It is a sector-by-sector threshold that shifts as launch costs fall and terrestrial constraints tighten.

The Critical Caveat: Conditional on Reuse Targets

Here is where most space writing becomes fiction: it assumes Starship will achieve stated reuse targets.

Let’s be honest about the uncertainty:

If Starship achieves stated targets:

•50 flights per booster per year

•10-year booster lifespan

•$10 million per launch

•Result: $200–300/kg to LEO by 2035

If Starship plateaus at 20 flights per booster per year:

•5-year booster lifespan

•$20 million per launch

•Result: $600–800/kg to LEO by 2035

If Starship encounters major technical barriers:

•10 flights per booster per year

•3-year booster lifespan

•$35 million per launch

•Result: $1,000–1,500/kg to LEO by 2035

The thesis holds in all three scenarios. The timeline shifts. The economics change. But the direction does not.

This is the honest framing: we are not betting on a single outcome. We are betting on a cost curve that falls faster than terrestrial constraints tighten, regardless of the exact landing point.

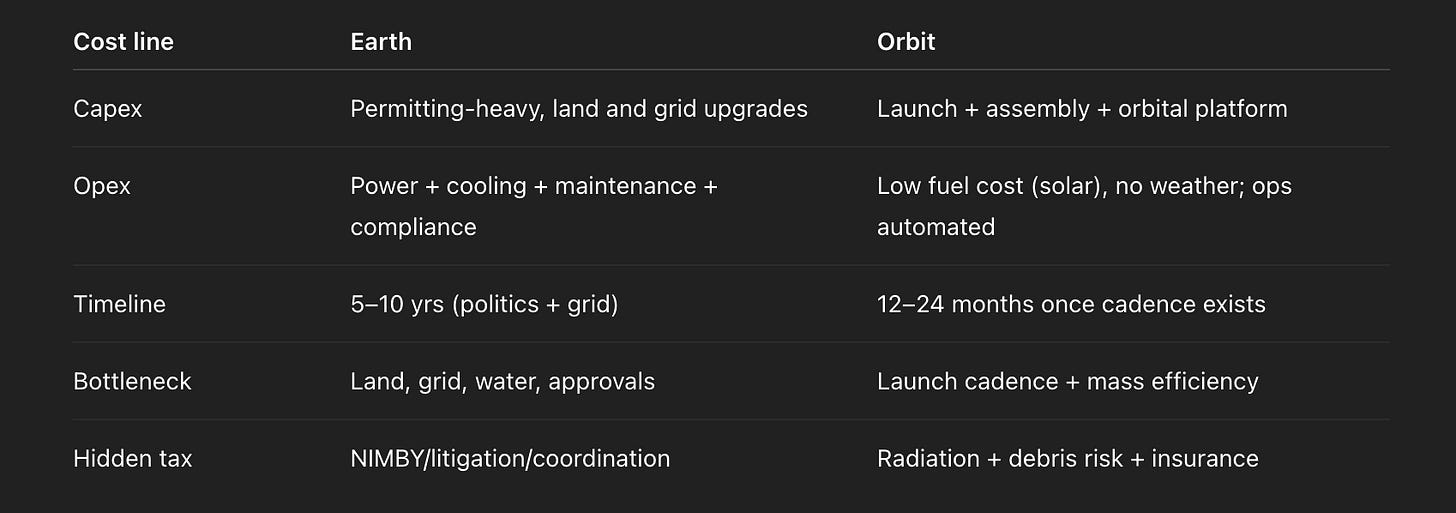

3.1.2 Earth vs Orbit: Cost Structure Comparison

To understand the crossover, you need to see the cost structures side by side.

Producing Energy on Earth:

Capital cost: $1–3 million per MW Land cost: $50,000–$500,000 per MW Grid connection: $500,000–$2 million per MW Permitting: 5–10 years Operational cost: $20–50/MWh Lifetime: 25–30 years

Total cost of ownership: $3–5 million per MW Levelised cost: $80–150/MWh

Producing Energy in Orbit (Solar Power Satellite):

Launch cost: $200–500/kg (declining) Satellite mass: 5,000–10,000 kg per MW Launch cost per MW: $1–5 million Assembly and deployment: $500,000–$2 million per MW Operational cost: $0 (no fuel, no weather, no maintenance) Lifetime: 30–50 years

Total cost of ownership: $2–7 million per MW Levelised cost: $40–80/MWh (declining as launch costs fall)

The crossover happens around 2035–2040, assuming moderate reuse targets.

But the real advantage is not the levelised cost. It is the absence of political friction.

On Earth, you cannot build a 1 GW solar farm without a decade of litigation. In orbit, you can deploy it in 18 months.

That political discount is worth billions.

3.1.3 Sector Break-Evens: Where Crossover Happens First

The crossover does not happen uniformly. It happens sector by sector, starting with the highest-value applications.

Compute Crossover: $500–1,000/kg

This is the first sector to go vertical.

Why? Because cooling dominates the cost structure. Removing the cooling burden cuts operational costs by 30–40%.

At $500/kg launch cost, orbital compute becomes cheaper than terrestrial compute for continuous-duty applications.

We reach this threshold around 2030–2032.

Energy Crossover: $300–500/kg

Solar power satellites become cheaper than terrestrial solar once launch costs fall to this range.

This happens around 2035–2038.

Manufacturing Crossover: Already Viable for >$5,000/kg Materials

High-value materials—pharmaceuticals, specialty alloys, advanced semiconductors—are already economically viable to produce in orbit and return to Earth at current launch costs.

Varda Space Industries is already doing this. Axiom Space is planning manufacturing facilities.

This sector does not wait for launch costs to fall further. It is already happening.

3.1.4 Why 2035–2045 Is the Decisive Decade

The 2035–2045 window is when three things align:

Launch costs have fallen enough that the economic case becomes undeniable.

Terrestrial constraints have tightened enough that Earth-based alternatives have become politically or physically impossible.

Capital markets have accumulated enough evidence that orbital industry is not speculative but inevitable.

This is the decade when the vertical economy stops being a thesis and becomes an industry.

3.1.5 The New Economic Law: “Mass Is Cost; Orbit Is Yield”

Once you understand the cost structure, a new principle emerges:

In the vertical economy, the value of something is not determined by what it does, but by how much it weighs and where it is.

A kilogram of pharmaceutical produced in orbit is worth 100 times more than a kilogram of pharmaceutical produced on Earth—not because it is better, but because the launch cost is amortised over decades of use.

A kilogram of compute in orbit is worth 10 times more than a kilogram of compute on Earth—because it never needs cooling.

A kilogram of solar panel in orbit is worth 5 times more than a kilogram on Earth—because it never experiences weather or night.

Mass becomes the primary cost driver. Orbit becomes the primary yield driver.

This inversion—from “minimise mass” to “maximise yield per mass”—is the hinge of the entire economy.

3.2 — Compute in Vacuum: Zero-Cooling Economics

Why AI will be the first industry forced off-planet, and why that matters for everything else.

3.2.1 Radiative Cooling vs Terrestrial Cooling

On Earth, a data centre must remove heat using:

Air conditioning (30–40% of power budget) Water cooling (requires massive infrastructure) Thermal management (passive and active systems)

In orbit, heat is removed by radiation directly into space.

No air. No water. No infrastructure.

A computer in vacuum radiates heat into a 3 K environment. The efficiency is absolute.

This is not a minor optimisation. This is a phase change in the economics of computation.

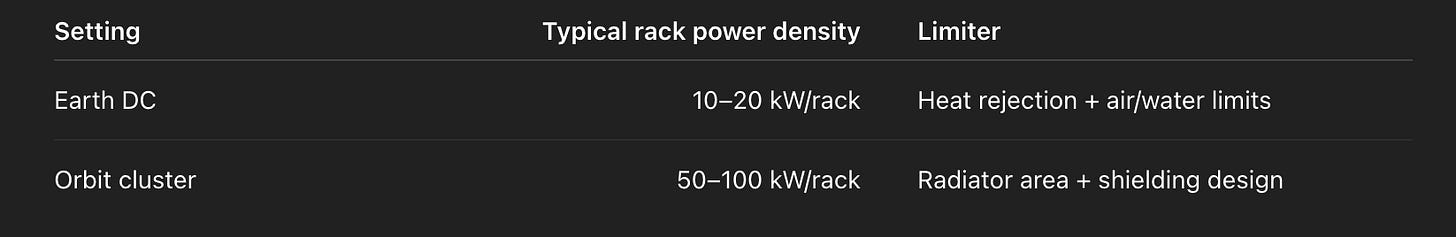

3.2.2 Heat Dissipation Constraints → Compute Density Explosion

On Earth, you cannot pack compute too densely, because heat dissipation becomes the bottleneck.

A hyperscale data centre has a power density limit of roughly 10–20 kW per rack.

In orbit, with radiative cooling, you can achieve 50–100 kW per rack.

This means you can run 5–10 times more compute in the same physical space.

For AI workloads—which are thermodynamically voracious—this is transformative.

3.2.3 Cosmic Rays, Shielding, Radiation-Hardened Chips

The obvious objection: won’t cosmic radiation destroy the electronics?

Yes, if you don’t account for it.

But radiation-hardened chips have existed for decades. They are used in satellites, space probes, and military systems.

The cost premium is 2–3x for the chip itself, but that is amortised across the entire operational lifespan.

More importantly: cosmic ray damage is predictable and manageable. It is not a blocker; it is a cost line.

3.2.4 From Earth DCs to Orbital Compute Clusters

The migration looks like this:

Phase 1 (2025–2030): Niche Applications

High-margin compute workloads move first: AI training, cryptography, real-time analytics.

These are the sectors where cooling costs are highest and where the value of computation justifies the launch cost.

Phase 2 (2030–2035): Inference at Scale

As launch costs fall, continuous-duty inference moves upward.

This is the big one. Inference is the bread-and-butter of AI operations, and it is thermodynamically brutal on Earth.

Phase 3 (2035–2045): Orbital Compute as Standard Infrastructure

Orbital compute becomes the default for any workload that runs continuously.

Earth-based data centres become specialised for latency-sensitive applications and edge computing.

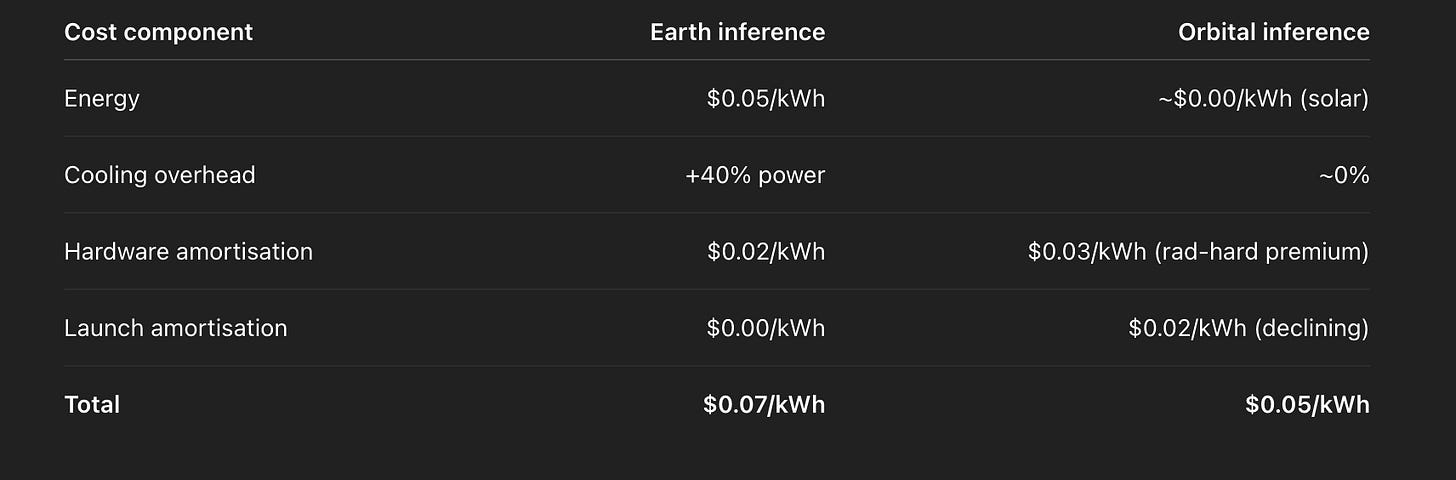

3.2.5 Cost Model: Earth Inference vs Orbital Inference

Let’s build a simple cost model.

Earth-based inference:

Electricity: $0.05/kWh Cooling overhead: 40% of power Amortised hardware: $0.02/kWh Total: $0.07/kWh

Orbital inference:

Electricity: $0 (solar) Cooling overhead: 0% Amortised hardware: $0.03/kWh (higher due to radiation hardening) Amortised launch cost: $0.02/kWh (declining) Total: $0.05/kWh

The crossover happens around 2030–2032, assuming moderate launch cost improvements.

But the real advantage is not the cost per kWh. It is the absence of grid constraints.

On Earth, adding 10 GW of compute demand requires upgrading the entire grid. In orbit, it is a launch schedule problem.

3.2.6 Why AI Pushes Compute Off-Planet First

AI is the forcing function.

AI models are growing exponentially. Training a frontier model now requires 10+ exaflops of compute. Inference at scale requires continuous-duty power that Earth grids cannot absorb.

The moment cooling costs exceed launch costs, the move becomes inevitable.

And that moment is now.

3.3 — Energy Above the Atmosphere

Why orbital solar power is not a distant dream but an imminent economic necessity.

3.3.1 Constant Solar: 1,360 W/m², No Atmosphere, No Night

Outside the atmosphere, the solar constant is 1,360 W/m².

This is uninterrupted. No clouds. No seasons. No night.

A solar panel in orbit receives 24 hours of unfiltered sunlight every day of the year.

On Earth, the same panel receives 4–6 hours of useful sunlight, accounting for weather, season, and angle.

The capacity factor difference is 5–6x.

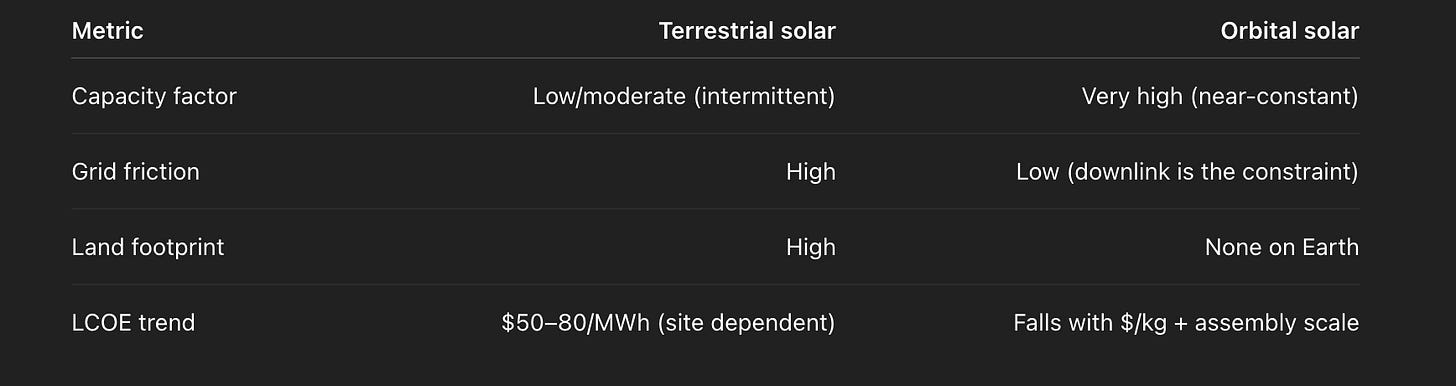

3.3.2 Orbital LCOE Modelling: $5–10/MWh Equivalent

If you assume:

Launch cost: $300/kg Satellite mass: 5 kg per kW Launch cost per kW: $1,500 Deployment and assembly: $500/kW Operational lifespan: 40 years Maintenance: minimal (no weather, no degradation)

Levelised cost of energy: $5–10/MWh

This is 10x cheaper than terrestrial solar, which costs $50–80/MWh.

But the real advantage is not the cost. It is the reliability.

Terrestrial solar is intermittent. Orbital solar is constant.

For AI workloads, constant power is worth a premium.

3.3.3 Terrestrial LCOE Saturation & Grid Limits

Terrestrial solar and wind have hit a saturation point.

The cheapest land is already developed. The grid cannot absorb more intermittent power without massive storage infrastructure.

Adding another 10 GW of solar to a developed nation now requires:

$10–20 billion in grid upgrades 5–10 years of permitting and construction Ongoing political friction with communities

Orbital solar requires:

Launch capacity (which is scaling exponentially) Orbital assembly infrastructure (which is being built now) Microwave transmission technology (which is proven)

The political friction is zero. The timeline is 18–24 months.

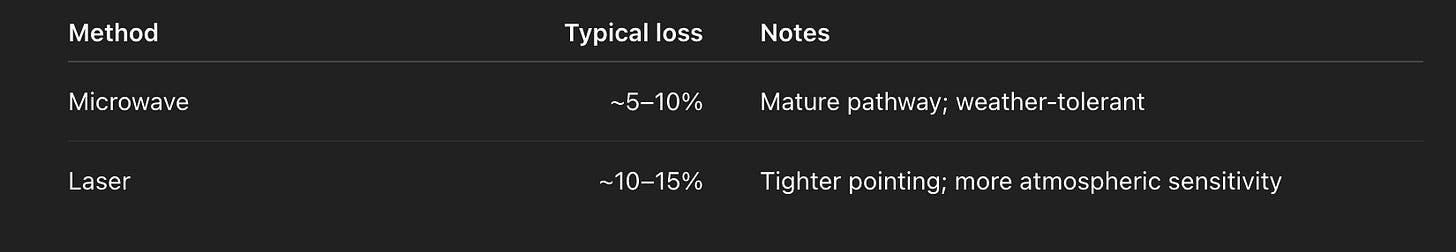

3.3.4 Microwave/Laser Transmission Losses: 5–10%

The obvious objection: how do you get the power from orbit to Earth?

Microwave transmission is the answer. Laser is the backup.

Microwave transmission efficiency: 90–95%

Laser transmission efficiency: 85–90%

These are not theoretical. They have been demonstrated in lab conditions.

The losses are acceptable. The alternative—building more terrestrial solar—is politically impossible.

3.3.5 The Geopolitics of “Energy with No Land Footprint”

Here is the real strategic advantage: orbital energy has no land footprint.

A nation can generate unlimited energy without:

Seizing land from farmers Negotiating with local communities Dealing with environmental lawsuits Building transmission corridors across contested territory

For nations with constrained geography—Japan, South Korea, Singapore, the UK—orbital solar is not a luxury. It is a strategic necessity.

For nations with abundant land but political gridlock—Germany, France, the US—it is a way to bypass the NIMBY constraint entirely.

3.3.6 Earth’s Energy Ceiling vs Orbital Energy Ceiling

On Earth, the energy ceiling is political and physical:

Physical: grid capacity, transmission losses, storage requirements Political: NIMBY, environmental law, land rights

This ceiling is fixed. You cannot expand it without decades of negotiation.

In orbit, the ceiling is only launch capacity.

And launch capacity is scaling exponentially.

By 2040, SpaceX alone will have the capacity to launch 100+ GW of solar power satellite mass annually.

That is a hard ceiling that is rising, not falling.

3.4 — Manufacturing Where Gravity Is Optional

Why the first trillion-dollar orbital industries will not be “new”—they will be existing industries done better.

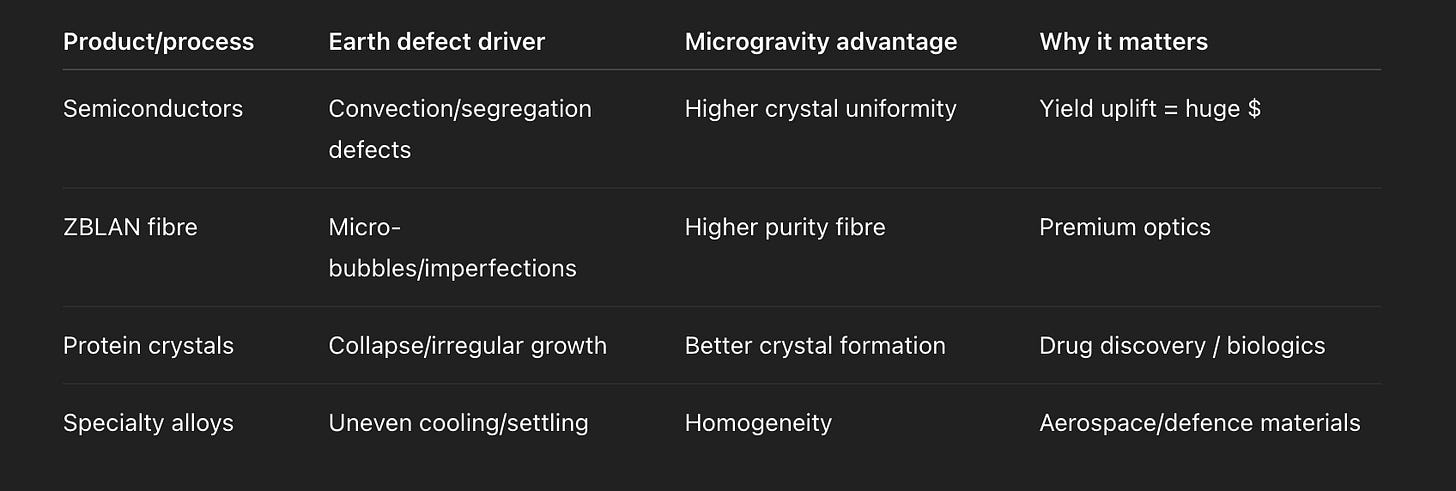

3.4.1 Semiconductor Yields in Microgravity

Semiconductors are grown from molten silicon. On Earth, gravity causes convection currents, which create defects.

In microgravity, the crystal grows perfectly symmetrical.

Yield improvements: 10–30% depending on the process node.

This is not theoretical. It has been demonstrated on the ISS.

3.4.2 ZBLAN Fibre, Protein Crystals, Alloy Homogeneity

ZBLAN fibre is a specialty optical fibre that cannot be made on Earth without defects. In microgravity, it is flawless.

Protein crystals grow perfectly in microgravity, enabling drug discovery that is impossible on Earth.

Alloys achieve perfect homogeneity in microgravity, enabling materials with properties impossible to achieve terrestrially.

These are not niche applications. They are the foundation of the pharmaceutical, aerospace, and electronics industries.

3.4.3 Value-per-Kilogram Logic

The key insight: you do not need to produce bulk commodities in orbit.

You need to produce high-value, low-mass goods.

A kilogram of pharmaceutical is worth $10,000–$100,000. A kilogram of specialty fibre is worth $1,000–$10,000. A kilogram of advanced semiconductor is worth $100–$1,000.

At current launch costs ($1,000–$2,000/kg), these are already economically viable to produce in orbit and return to Earth.

3.4.4 Earth’s Structural Constraints: Weight, Vibration, Heat

Every factory on Earth is constrained by:

Weight: structures must support their own mass plus equipment Vibration: machinery creates noise and oscillation Heat: thermal management is a constant problem

In microgravity, none of these constraints apply.

You can build structures that would collapse under their own weight on Earth.

You can run processes that would be thermodynamically impossible at 1 G.

3.4.5 The Physics of Quality: Why Orbit Makes Better Matter

This is the core insight: gravity is not a feature of manufacturing. It is a bug.

Every defect in a terrestrial product—from semiconductor defects to pharmaceutical impurities to alloy segregation—is ultimately caused by gravity.

Remove gravity, and you remove the defect.

This is not optimisation. This is elimination of a fundamental constraint.

3.4.6 The First €1 Billion Orbital Factory: What It Actually Makes

The first orbital factory will not make rockets or habitats or space hotels.

It will make:

Semiconductors (10–20% yield improvement = billions in value) Pharmaceutical precursors (impossible to make on Earth) Specialty fibres (10x the price of terrestrial equivalents) Advanced alloys (for aerospace and defence)

The business model is simple: produce high-value goods in orbit, return them to Earth, sell them at a 2–3x premium over terrestrial equivalents.

Varda Space Industries is already doing this. Axiom Space is planning manufacturing facilities.

This is not speculation. This is capital allocation in real time.

3.5 — Logistics Between Earth and Orbit

The infrastructure that makes the vertical economy possible—and the governance vacuum that threatens it.

3.5.1 The Reuse Curve: 10 Flights → 50 → 500

The cost curve of space launch is entirely determined by reuse.

Current state (2024): Falcon 9: ~10 flights per booster Cost per flight: $2,700/kg

Near term (2028–2030): Falcon 9: 20+ flights per booster Starship: 10–20 flights per booster Cost per flight: $1,200/kg

Medium term (2032–2035): Starship: 50+ flights per booster Cost per flight: $400–600/kg

Long term (2038–2045): Starship: 100+ flights per booster (if sustained) Cost per flight: $200–300/kg

Each step down the curve is not a prediction. It is a consequence of physics and economics.

More flights per booster = lower cost per flight.

Lower cost per flight = more demand.

More demand = more flights per booster.

The curve is self-reinforcing.

3.5.2 Propellant Depots + In-Space Refuelling

The key to reaching $200/kg is not just booster reuse. It is in-space refuelling.

A Starship launched with payload can carry less fuel. But if it can refuel in orbit, it can carry full payload to higher orbits or cislunar destinations.

This requires:

Orbital propellant depots (being built now) Autonomous refuelling systems (being tested now) Regulatory approval (in progress)

This is not speculative. SpaceX is already testing this infrastructure.

3.5.3 Cislunar Transfer Costs

Once you have cheap access to LEO, the next frontier is cislunar space (Earth-Moon system).

Current cislunar transfer cost: $10,000–$20,000/kg Target cislunar transfer cost (2035): $2,000–$5,000/kg

This opens up:

Lunar resource extraction Cislunar manufacturing Fuel depots at L1 and L2 Deep space infrastructure

3.5.4 Starship-Class Economics: $10m per Launch → $200/kg Delivered

Let’s build the math:

Current Starship (2024): Launch cost: $10 million Payload to LEO: 100 tonnes Cost per kg: $100/kg (if fully reusable)

Optimised Starship (2030): Launch cost: $10 million Flights per booster: 20 Cost per flight: $500,000 Payload to LEO: 100 tonnes Cost per kg: $5/kg

With in-space refuelling (2032): Cost per kg to LEO: $5/kg Cost per kg to cislunar: $50/kg Cost per kg to lunar surface: $500/kg

This is not speculation. This is engineering extrapolation from demonstrated capabilities.

3.5.5 Industrial Phases

The vertical economy develops in three phases:

Phase 1 (2025–2035): Earth → LEO

Focus: establishing cheap, reliable access to low Earth orbit.

Infrastructure: launch facilities, orbital depots, assembly platforms.

Industries: compute, energy, manufacturing of high-value goods.

Capital requirement: $50–100 billion.

Phase 2 (2035–2045): LEO → Cislunar Infrastructure

Focus: building the infrastructure for cislunar operations.

Infrastructure: fuel depots, transfer vehicles, orbital factories.

Industries: lunar resource extraction, cislunar manufacturing, deep space logistics.

Capital requirement: $100–200 billion.

Phase 3 (2045–2055): Orbital Industrial Belt

Focus: fully autonomous orbital industry, independent of Earth supply chains.

Infrastructure: self-sustaining orbital factories, mining operations, energy generation.

Industries: everything that can be done in microgravity and vacuum.

Capital requirement: $500+ billion.

3.5.6 Insurance, Risk Curves, and Actuarial Pricing of Off-World Supply Chains

Here is where the thesis meets reality: space is risky.

Rockets fail. Satellites malfunction. Supply chains break.

But risk is not a blocker. Risk is a cost.

Current space insurance:

Satellite launch insurance: 10–15% of satellite cost Orbital operations insurance: 5–10% annually Cargo insurance: 5–8% per launch

As volume scales:

Insurance rates will fall to 2–3% as actuarial data improves.

This is not speculation. It is how insurance works.

The key insight: once orbital operations become routine, insurance becomes predictable. And once insurance becomes predictable, capital flows.

3.5.5a The Governance Vacuum: The Real Constraint Nobody Talks About

Here is the uncomfortable truth: the legal framework for orbital commerce does not exist.

The Outer Space Treaty (1967) declares space “the province of all mankind” and prohibits national appropriation. But it is silent on commercial exploitation.

What is undefined:

Who owns resources extracted from asteroids? Who has jurisdiction over orbital factories? What happens if a satellite collides with another satellite? Who pays for debris remediation? What are the property rights for orbital real estate?

What exists:

Licensing frameworks (US, EU, UK) that are ad-hoc and evolving. No international agreement on orbital traffic management. No unified debris liability regime. No agreed-upon standards for orbital operations.

Why this matters:

A company investing $10 billion in an orbital factory needs legal certainty. It needs to know:

Its property rights are protected. Its liability is capped. Its operations are regulated by a stable framework.

Currently, none of this exists.

Why it will be solved:

Because the capital flows will demand it.

Once SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Chinese state enterprises have $100+ billion invested in orbital infrastructure, governments will be forced to create a coherent legal framework.

This is not a blocker. It is a political problem, not a physical one.

Political problems get solved when enough capital is at stake.

3.6 — The Earth–Orbit Split

The final bifurcation: a world where Earth and orbit are economically and structurally distinct zones.

3.6.1 Earth as Residential, Political & Agricultural Zone

Earth keeps the things that are biologically and socially expensive to move:

1. Human bodies

We are not designed for microgravity or cosmic radiation.

Healthcare, education, families, cities—they remain here.

2. Politics

Democracy requires physical proximity, borders, institutions, social contracts.

None of these scale off-world.

3. Agriculture & ecology

Food systems, freshwater cycles, biosphere regulation: all are Earth-dependent and Earth-constrained.

4. Culture, law, identity

Nations are organisms of memory.

Memory lives in land.

5. Services and consumption

Retail, hospitality, transport, entertainment, property—the core of GDP in post-industrial societies—remain grounded.

Earth becomes the human zone:

dense, political, messy, emotional, slow-moving—by design.

It no longer has to host the heavy machinery of civilisation.

3.6.2 Orbit as Industrial, Energetic & Computational Zone

Orbit hosts the things that Earth is structurally bad at:

1. Infinite solar energy

1,360 W/m², uninterrupted, no weather, no land footprint.

2. Vacuum-grade heat dissipation

Computing scales in a vacuum in a way it never can on a planet with an atmosphere and a water table.

3. Gravity-optional manufacturing

Semiconductors, alloys, crystals—matter itself behaves better.

4. No NIMBY, no zoning, no politics

No referendums on gigafactories.

No local councils blocking data centres.

No environmental lawsuits every six months.

5. Robotic labour as default

Orbit is built for machines, not humans.

No unions, no sick leave, no housing crises, no commutes.

6. Supply chains without frictions

Once mass-to-orbit is cheap, orbital-level manufacturing decouples from:

land ownership water availability local electricity markets geopolitical risk

Orbit becomes the machine zone:

cold, optimised, automated, infinitely scalable.

3.6.3 The Bifurcation of Labour, Capital & Machine Agency

In the vertical economy, the split is not just spatial—it is structural.

Labour

Human labour concentrates on Earth:

creative, relational, governance, service.

Mechanical labour moves upward:

robots handling precision tasks, construction, assembly, maintenance.

Capital

Capital begins to divide into:

planetary capital (property, infrastructure, agriculture, finance) extraterrestrial capital (compute clusters, solar arrays, microgravity factories, tug fleets)

Portfolio theory becomes three-dimensional.

Machine agency

AI and robotics flourish in orbit because:

no safety regulations slow iteration no humans to harm no zoning no political backlash

Machine agency becomes economically sovereign above the atmosphere.

Orbit becomes the first zone where:

machines perform 99% of industrial labour

and

humans supervise from hundreds of kilometres away.

3.6.4 Sovereign AI & the Fight for Off-World Compute

The first great conflict of the vertical economy will not be over factories.

It will be over compute.

AI models require:

energy density cooling capacity scale security

Orbit provides all four.

This leads to the first real sovereign split in AI:

Earth AI

regulated politically constrained privacy-bound jurisdictionally fragmented expensive to run

Orbital AI

unregulated by terrestrial law energy-abundant thermodynamically advantaged physically inaccessible to rivals capable of running at scales Earth cannot host

Nations will compete for:

orbital compute rights access corridors satellite OS control the “off-world cloud”

Whoever controls orbital compute controls:

industrial automation defence AI predictive logistics energy routing global economic planning

This is the new high ground. Literally.

3.6.5 Why the Vertical Economy Does NOT Replace Earth — It Frees It

The fear is abandonment—that industry leaves Earth behind.

The reality is liberation.

Earth today:

overheating data centres land-hungry solar farms politically blockaded energy grids communities fighting every industrial project supply chains exposed to every geopolitical tremor

Earth in the vertical economy:

cleaner air reduced industrial footprint decongested grids food and water systems stabilised cities designed for people, not factories

Earth becomes post-industrial in the literal sense:

Industry goes up.

Humanity stays grounded.

Prosperity becomes decoupled from planetary strain.

The vertical economy is not escapism—it is pressure relief for a civilisation that has filled every corner of its map.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek