📑 CONTENT — PART V

5.0 — The Human Rearrangement

Why the removal of labour as a constraint breaks the social contract, dissolves wage-based identity, and forces civilisation to redesign meaning, income, and freedom.

5.0.1 Labour as the Load-Bearing Assumption

5.0.2 Why Scarcity Made Humans Legible to the System

5.0.3 The Moment Labour Becomes Abundant

5.0.4 Productivity Without Participation

5.0.5 Why This Is a Design Problem, Not a Moral One

5.1 — Work: The System Humans Mistook for Purpose

Employment was never about meaning — it was about distribution, discipline, and coordination at scale.

5.1.1 Jobs as an Allocation Mechanism

5.1.2 Wages as Social Control

5.1.3 The Collapse of Job-Based Identity

5.1.4 Effort Survives Employment

5.1.5 Why the End of Work Is Not the End of Contribution

5.2 — Income Without Labour

When machines produce value, income must be redesigned — not improvised.

5.2.1 Wages as a Historical Artifact

5.2.2 Capital, Machines, and Yield

5.2.3 Why UBI Solves Stability but Not Meaning

5.2.4 Ownership, Dividends, and Participation Models

5.2.5 The Risk of Passive Abundance

5.3 — Status After Productivity

When output stops signalling worth, status games mutate — fast.

5.3.1 Status as a Scarcity Signal

5.3.2 Intelligence Inflation and Credential Collapse

5.3.3 Meritocracy Without Metrics

5.3.4 The Return of Non-Economic Hierarchies

5.3.5 Status Failure as a Political Risk

5.4 — Meaning After Automation

If meaning is not designed, nihilism fills the gap — not leisure.

5.4.1 Why Boredom Is a Red Herring

5.4.2 Nihilism as a Systems Failure

5.4.3 Voluntary Difficulty as a Human Need

5.4.4 Craft, Mastery, and Chosen Excellence

5.4.5 Why Meaning Cannot Be Automated

5.5 — The Failure Modes

Abundance does not guarantee freedom — it enables control if badly designed.

5.5.1 Surveillance Welfare States

5.5.2 Behavioural Credit and Soft Coercion

5.5.3 Managed Populations vs Free Citizens

5.5.4 The Illusion of Choice Under Abundance

5.5.5 Why These Outcomes Are Political, Not Inevitable

5.6 — Designed Abundance vs Drifted Abundance

Every previous social order was designed. This one will be too — explicitly or by accident.

5.6.1 Institutional Lag as the Real Threat

5.6.2 Why Architecture Beats Ideology

5.6.3 Who Designs the Rules of Post-Labour Life

5.6.4 Freedom as an Explicit Design Variable

5.6.5 The Difference Between Liberation and Permission

5.7 — Education After Scarcity

When credentials stop rationing opportunity, education must change function.

5.7.1 Education as Filtering vs Formation

5.7.2 Learning Without Economic Threat

5.7.3 Skill as Identity, Not Insurance

5.7.4 The Death of Human Capital Theory

5.7.5 Curiosity as Civic Infrastructure

5.8 — The New Social Contract

The labour-for-survival bargain ends. Something replaces it.

5.8.1 Rights Detached from Employment

5.8.2 Contribution Without Coercion

5.8.3 Citizenship in an Automated Economy

5.8.4 What States Owe Humans — and What They Don’t

5.8.5 The Risk of Infantilised Societies

5.9 — Freedom After Scarcity

Abundance either frees humans — or perfects their containment.

5.9.1 Abundance as Liberation or Control

5.9.2 Why Freedom Is Not Automatic

5.9.3 The Temptation to Optimise Humans

5.9.4 The Minimum Viable Freedom

5.9.5 The Choice Embedded in the Architecture

5.0 — The Human Rearrangement

Why the removal of labour as a constraint breaks the social contract, dissolves wage-based identity, and forces civilisation to redesign meaning, income, and freedom.

For most of modern history, humans were legible to the economic system because they were scarce.

Labour scarcity was not just an input constraint — it was the organising principle of society. It determined who mattered, who was paid, who was educated, who migrated, who fought wars, and who retired. It gave governments a tax base, firms a cost curve, and individuals a place in the social order.

That era is ending.

Not because humans disappear — but because human effort stops being the limiting factor in production, logistics, analysis, and coordination. Machines do not need wages, weekends, visas, pensions, or political consensus. Once they reach sufficient generality, they do not merely compete with labour — they make labour optional.

This is not a story about job loss.

It is a story about what happens when the system no longer needs humans in order to function.

Every previous economic transition still required people to work in order to survive. Agriculture needed farmers. Industry needed factory hands. Services needed clerks, managers, and professionals. Even automation until now mostly changed which jobs existed, not whether work itself was required.

This transition is different.

When labour stops being scarce, the social contract — which quietly assumed that survival is exchanged for participation — collapses. Not politically. Mechanically.

What follows is not dystopia by default.

But neither is it utopia.

It is a design problem — and like all design problems, the outcome depends on who sets the rules, which constraints are chosen, and which incentives are allowed to compound.

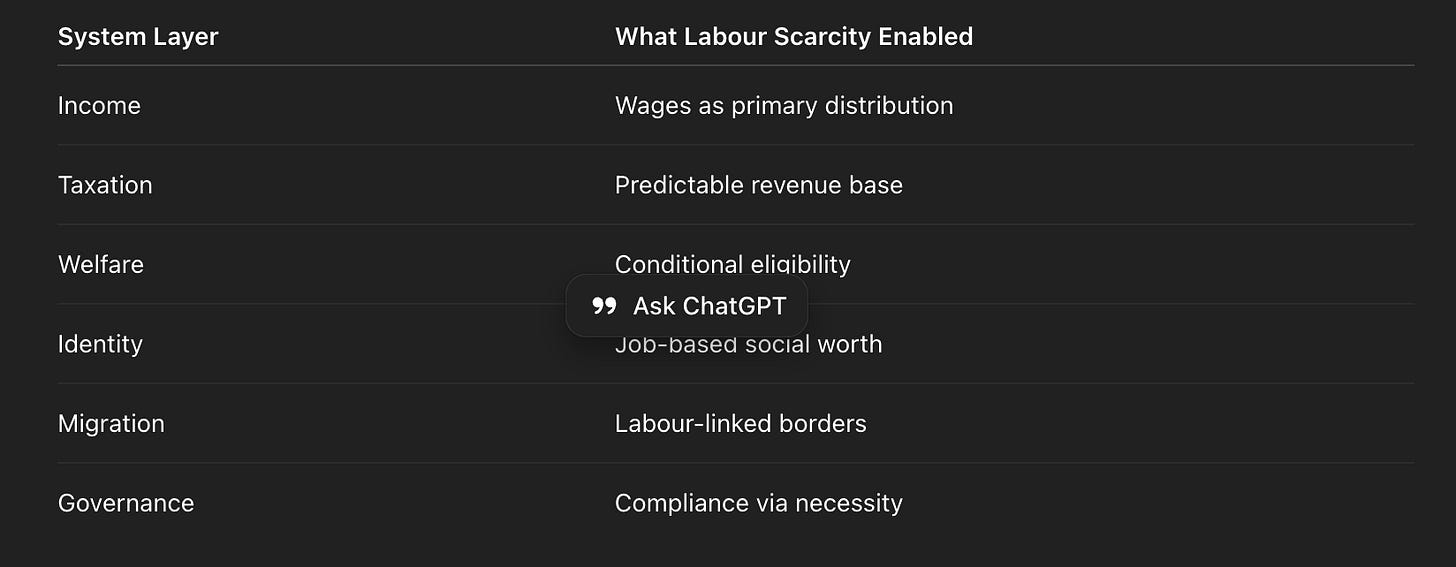

5.0.1 Labour as the Load-Bearing Assumption

Modern civilisation is built on a single, rarely questioned premise:

humans must work in order to eat.

That assumption holds up:

wage systems

taxation

welfare eligibility

immigration policy

education pathways

identity and status

moral judgements about worth

It is the silent beam holding the structure together.

Remove it, and the building does not collapse immediately — but it becomes unstable. Institutions continue to operate as if labour scarcity still exists, even when the economy no longer behaves that way.

This is why current debates feel incoherent. We are arguing about minimum wages, job creation, and retraining programmes inside a system where the underlying scarcity condition is failing.

The problem is not unemployment.

The problem is that labour is no longer the load-bearing variable.

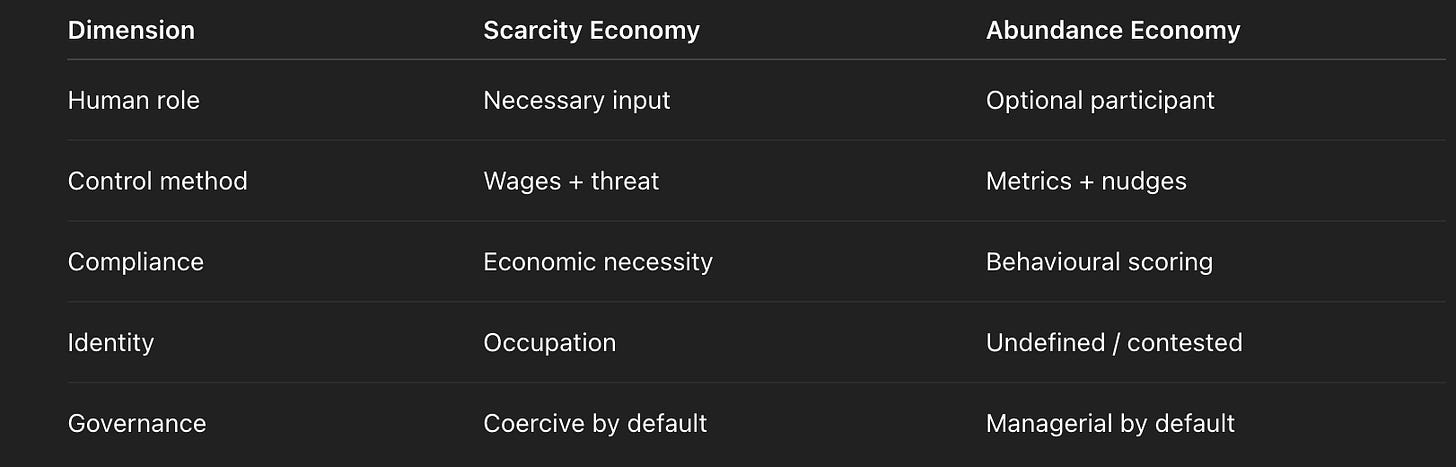

5.0.2 Why Scarcity Made Humans Legible to the System

Scarcity simplifies governance.

When labour is scarce:

effort can be priced

productivity can be measured

contribution can be compared

compliance can be incentivised

Wages were not just income — they were signals.

Jobs were not just tasks — they were identity containers.

The system could “see” humans because their participation was necessary. If you wanted housing, healthcare, status, or security, you had to be economically legible — employed, taxed, ranked.

Scarcity made people governable.

Abundance does not.

When machines can produce value without human input, the system loses its primary method of sorting, disciplining, and rewarding citizens. That is not a moral crisis. It is an administrative one.

And systems respond to administrative crises in predictable ways: by inventing new metrics, new controls, or new forms of conditionality — unless deliberately redesigned.

5.0.3 The Moment Labour Becomes Abundant

Labour abundance does not arrive with an announcement. It creeps in through edge cases:

AI handles the junior work.

Robotics handles the repetitive work.

Systems coordination replaces middle management.

Productivity rises while headcount flattens.

Output increases without proportional employment.

At first, this looks like efficiency.

Then it looks like polarisation.

Eventually, it looks like decoupling.

The critical moment is not mass unemployment.

It is when economic output continues without human participation being required at the margin.

At that point, the wage system stops being a natural distribution mechanism and becomes a historical artifact — still present, still defended, but no longer functionally central.

This is where most societies are heading — whether they admit it or not.

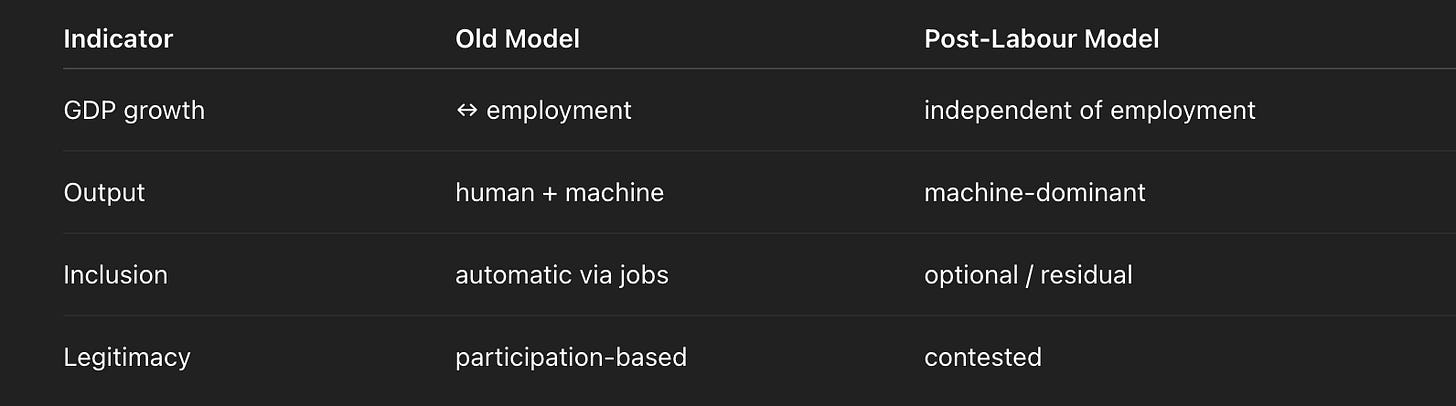

5.0.4 Productivity Without Participation

The deepest shock is not economic — it is psychological.

For centuries, productivity implied participation:

If the economy grows, people are involved.

That link breaks.

Machines can now:

increase output

lower costs

optimise systems

compound capital

without expanding human inclusion.

This creates a condition modern politics is not designed to handle: growth without belonging.

GDP can rise while large portions of the population are no longer structurally necessary to production. That does not automatically create misery — but it destroys the old promise that “the system needs you.”

Once that promise disappears, meaning must come from somewhere else — or be imposed.

5.0.5 Why This Is a Design Problem, Not a Moral One

It is tempting to frame this transition morally:

greedy elites

lazy populations

technocratic overreach

soulless machines

That framing is comforting — and wrong.

The system is not becoming inhuman because humans failed.

It is becoming post-labour because technology succeeded.

The question is not whether abundance is good or bad.

The question is whether abundance is designed or drifted into.

Drift produces:

surveillance welfare

behavioural control

passive populations

managed dependency

Design can produce:

freedom without precarity

contribution without coercion

dignity without artificial scarcity

meaning without enforced labour

Nothing about the post-labour world is automatic.

Every outcome is architectural.

And architecture always wins.

5.1 — Work: The System Humans Mistook for Purpose

Employment was never about meaning — it was about distribution, discipline, and coordination at scale.

Modern societies tell a comforting story about work.

That jobs give life purpose.

That employment dignifies.

That contribution is inseparable from occupation.

None of this is historically true.

Work became morally loaded only when it became economically necessary to organise millions of people at scale. Purpose was added later — as glue.

Employment is not a timeless human institution. It is a logistical solution to a specific problem: how to allocate resources, coordinate effort, and maintain order in large, industrial societies where survival depends on continuous production.

Once that problem changes, the institution does too.

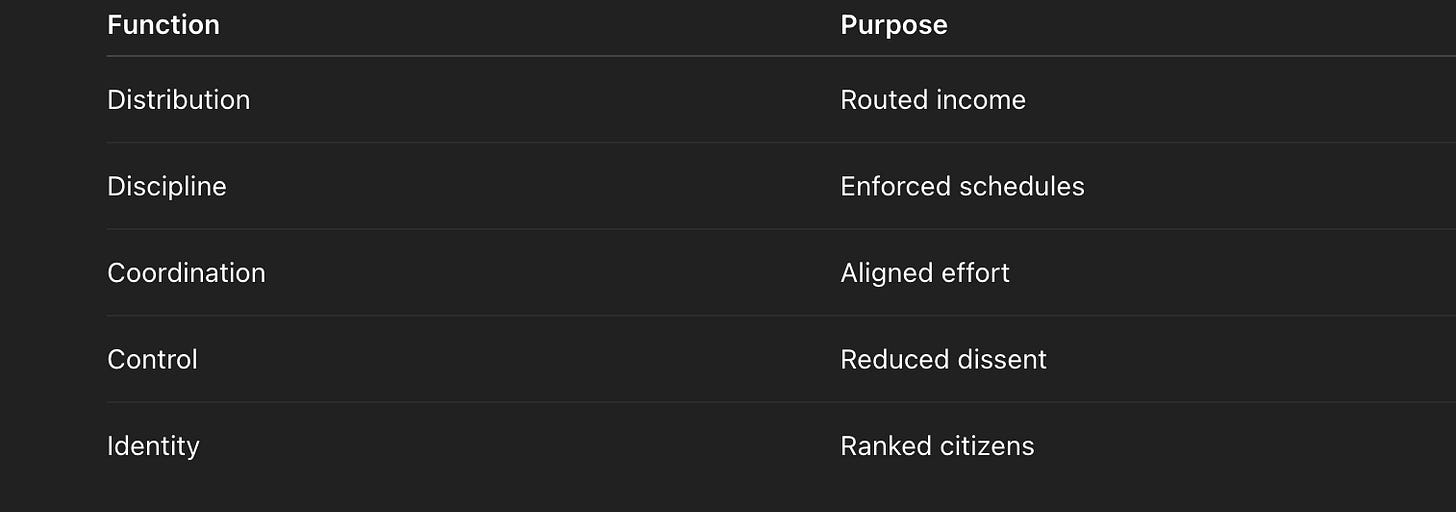

5.1.1 Jobs as an Allocation Mechanism

At its core, a job is not a calling.

It is a routing system.

Jobs decide:

who gets income

who gets housing

who gets healthcare

who gets status

who gets to stay in a country

Employment became the master key that unlocked access to almost everything else. Not because it was meaningful — but because it was administratively efficient.

If you want to distribute scarce resources at scale, tying access to participation is brutally effective.

Jobs were the API between humans and the economy.

5.1.2 Wages as Social Control

Wages were never just compensation.

They were behavioural signals.

A wage tells you:

when to wake up

where to live

how much risk you can take

whether you can dissent

when you can stop

Miss a wage, and the consequences are immediate and personal. That made wages a powerful stabiliser — far more effective than ideology or law.

The genius of the wage system was not fairness.

It was compliance without force.

You didn’t need soldiers when you had rent.

5.1.3 The Collapse of Job-Based Identity

For most people, identity quietly fused with occupation:

“What do you do?”

The question wasn’t curiosity. It was classification.

Your job told others:

your social rank

your intelligence proxy

your political tribe

your future trajectory

As labour stops being central to production, this identity structure fractures. Not everyone at once — but unevenly, painfully.

Some professions hollow out.

Others become prestige markers divorced from output.

Many disappear entirely.

What replaces job-based identity is not obvious — and the vacuum is dangerous. When identity loses its organising axis, people seek substitutes: ideology, grievance, tribe, nostalgia.

This is not a cultural problem.

It is a structural one.

5.1.4 Effort Survives Employment

The end of work is not the end of effort.

Humans do not stop striving when wages disappear.

They stop performing effort for survival.

What remains is effort chosen rather than coerced:

mastery

craft

exploration

competition

contribution without compulsion

Every society that confuses employment with effort ends up fearing a future that never arrives — a population of idle, purposeless citizens.

That fear misunderstands human nature.

What disappears is not activity.

What disappears is forced participation in systems that no longer need it.

5.1.5 Why the End of Work Is Not the End of Contribution

Contribution predates employment.

It will outlive it.

People build, teach, organise, compete, create, and care even when survival is guaranteed — sometimes more intensely.

The mistake modern societies make is assuming that contribution must be purchased.

When machines produce abundance, the question is not how to make humans work.

It is how to recognise, reward, and integrate contribution without coercion.

That requires new institutions.

New signals.

New forms of status and participation.

And above all, it requires abandoning the idea that dignity is something you earn by being economically useful to a system that no longer needs you.

Work was never sacred.

It was functional.

And its function is changing.

5.2 — Income Without Labour

When machines produce value, income must be redesigned — not improvised.

The wage is one of those inventions that feels permanent only because it has dominated our lifetimes. We treat employment as the normal way humans “earn”, as if paycheques are a law of nature rather than a coordination hack from the industrial age. But wages were never a moral truth. They were a distribution mechanism: a way to route purchasing power to the people whose labour was required to produce things.

That arrangement holds as long as labour is scarce and indispensable.

The moment labour stops being the bottleneck — because cognition becomes cheap and physical work becomes robotic — the wage system stops being the bloodstream of the economy and becomes a blockage. Output can rise while participation falls. Productivity can surge while the majority of citizens become economically irrelevant to production. You can call that progress, but you can’t run a society on it without redesigning how income flows.

This is the point most debates avoid. They drift into ideology because ideology is comforting. But the problem is mechanical: if human effort is no longer the price of production, what becomes the price of living?

5.2.1 Wages as a Historical Artifact

The wage system is new, historically speaking. For most of civilisation, people lived through access rather than employment: access to land, to guilds, to institutions, to patronage, to conquest, to family structure. Industrial capitalism didn’t invent income — it standardised it. It made wages legible, taxable, scalable, and politically stabilising. It turned “value” into hours, and hours into money.

That worked brilliantly when factories needed bodies and offices needed brains.

But once bodies and brains are no longer the limiting input, wages look less like the natural order and more like what they really are: a temporary interface between humans and machines.

5.2.2 Capital, Machines, and Yield

A post-labour economy does not eliminate capitalism. It purifies it.

When production is machine-driven, value accrues to the owners of machines, infrastructure, energy, compute, and the rights layered on top — data, IP, platforms, protocols. This is already visible in miniature. Shareholders earn without working. IP holders earn without producing. Infrastructure owners earn without operating.

AI and robotics don’t create a new logic. They scale the existing one until it dominates everything.

That’s why the “inequality debate” is misframed. This isn’t about greed or virtue. It’s about the routing of yield. If the highest-yield assets are automated systems, and ownership of those systems is narrow, then inequality becomes structural. You can tax it, scold it, regulate it — but unless you alter ownership and yield rights, you’re arguing with physics.

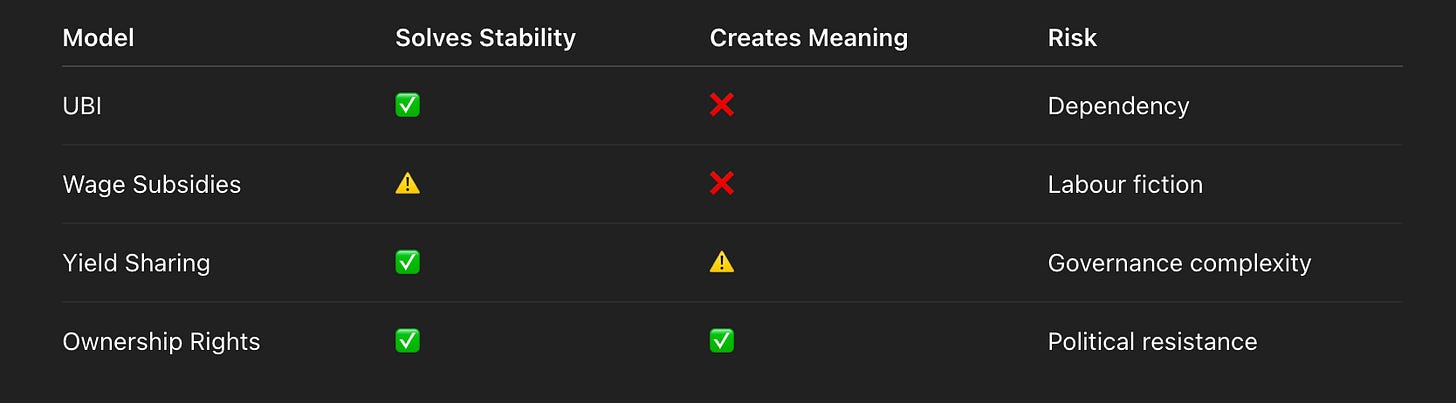

5.2.3 Why UBI Solves Stability but Not Meaning

Universal Basic Income is the first answer people reach for because it is clean. It solves the immediate failure mode: instability. People with guaranteed income don’t starve, don’t riot as easily, don’t detonate demand, don’t collapse housing markets through mass insolvency. UBI is a stabiliser.

But a stabiliser is not a civilisation.

UBI keeps the system from burning down; it doesn’t tell people what they’re for. Worse, if it arrives as a replacement for participation rather than a foundation for it, it risks turning citizens into dependents — safe, fed, and politically brittle. A society can be economically solvent and still spiritually bankrupt. It can provide comfort and still manufacture resentment.

UBI is necessary in a transition. It is not a complete architecture.

5.2.4 Ownership, Dividends, and Participation Models

If wages shrink because labour is no longer scarce, the replacement cannot be charity. It has to be a claim on yield.

The most functional post-labour systems will treat citizens less like employees and more like stakeholders. Not because it’s ethically fashionable — because it prevents the ownership class from becoming a permanent ruling class. The design space is wide: national machine dividends, sovereign AI funds, infrastructure yield sharing, data-rights pools, citizen equity models tied to the automated capital base.

The principle is simple and cold:

If machines replace labour, humans must replace wages with ownership or yield rights — at scale.

That isn’t socialism. It isn’t libertarianism. It’s the only way to keep mass prosperity connected to mass legitimacy.

5.2.5 The Risk of Passive Abundance

There’s a deeper trap, though — and it’s where techno-utopians quietly fail.

Abundance does not automatically produce freedom. It can produce sedation.

If income becomes a passive entitlement with no designed pathway to agency, contribution, mastery, and meaning, societies don’t collapse from poverty. They rot from inertia. Not because humans are lazy, but because humans require stakes. They need friction. They need chosen difficulty. They need the feeling that their actions matter.

So income architecture cannot be built in isolation. It has to be linked to the rest of Part V: status systems, education, contribution, civic identity. Money keeps people alive. It does not keep them human.

Income without labour is inevitable.

Whether it becomes liberation or containment is not.

That choice is design.

5.3 — Status After Productivity

When output stops signalling worth, status games don’t disappear. They mutate.

For most of modern history, productivity quietly did two jobs at once. It created goods and services, and it ranked people. Who earned more usually produced more — or at least appeared to. Wages became a proxy for value, and value became a proxy for virtue. The system wasn’t fair, but it was legible. You could tell who was winning by looking at their payslip, their job title, their postcode.

When labour decouples from production, that legibility collapses.

A society without productive scarcity doesn’t become egalitarian by default. It becomes confused. And confused societies do not abolish hierarchy — they invent new ones, often worse.

5.3.1 Status as a Scarcity Signal

Status is not vanity. It is a coordination tool.

Every civilisation needs a way to signal who is competent, trustworthy, admirable, or dangerous. In scarcity-based economies, productivity performed that function. If you could produce value, the system rewarded you, and others inferred that you were useful. Status followed output like a shadow.

Once machines do the producing, that signal fails.

If everyone’s income is partially detached from effort, status can no longer ride on wages without looking absurd. The result is a vacuum — and vacuums are never empty for long.

5.3.2 Intelligence Inflation and Credential Collapse

The first replacement hierarchy will be cognitive.

As AI makes intelligence cheaper, credentials inflate. Degrees multiply. Certifications metastasise. Everyone becomes “qualified”, which is another way of saying no one is. What was once a signal of capability becomes a participation trophy issued by institutions trying to remain relevant.

This is already visible. Universities market employability in a world where employment is thinning. Professional bodies defend standards in professions that software is quietly absorbing. Credentials rise in number as their information content collapses.

The system responds to abundance by pretending scarcity still exists.

It doesn’t work.

5.3.3 Meritocracy Without Metrics

Meritocracy only functions when merit can be measured. When output, effort, and reward are decoupled, merit becomes aesthetic. People argue about “impact”, “leadership”, “influence”, “creativity” — words that feel important because they are vague enough to be undefinable.

This is how meritocracy dies: not through rebellion, but through semantic drift.

Without clear metrics, power concentrates around those who control narratives rather than those who create value. Status becomes performative. Prestige migrates to visibility. Social capital replaces productive capital. Influence replaces contribution.

At that point, meritocracy doesn’t fail loudly. It dissolves politely.

5.3.4 The Return of Non-Economic Hierarchies

When economic signalling breaks, older hierarchies reassert themselves.

Cultural status. Moral status. Identity status. Proximity to institutions. Access to platforms. Alignment with dominant values. These are not new phenomena — they are pre-modern. What’s new is their return inside technologically advanced societies that believed they had outgrown them.

This is why post-labour societies risk becoming more judgemental, not less. When contribution is unclear, people compete over virtue. When productivity no longer distinguishes, ideology does the sorting.

Status games don’t vanish. They simply move from factories to feeds.

5.3.5 Status Failure as a Political Risk

This is not a sociological curiosity. It is a political fault line.

If a large population feels economically supported but socially illegible — fed but unrecognised — resentment builds. Not against machines, but against elites who appear to enjoy both abundance and status. Stability erodes not because people are poor, but because they feel unnecessary.

History is clear on this point: societies tolerate inequality far better than invisibility.

A post-labour economy that solves income but ignores status will not remain liberal for long. People will demand new hierarchies, even bad ones, simply to restore meaning and rank.

Which is why the next question matters more than income alone:

If productivity no longer confers status, what should?

That answer cannot be left to drift. If it is, the loudest, angriest, or most performative actors will design it by default.

Status, like income, must be redesigned — consciously, explicitly, and with restraint.

That design problem leads directly to the next one: meaning.

Because status without purpose is noise.

And abundance without meaning is corrosive.

5.4 — Meaning After Automation

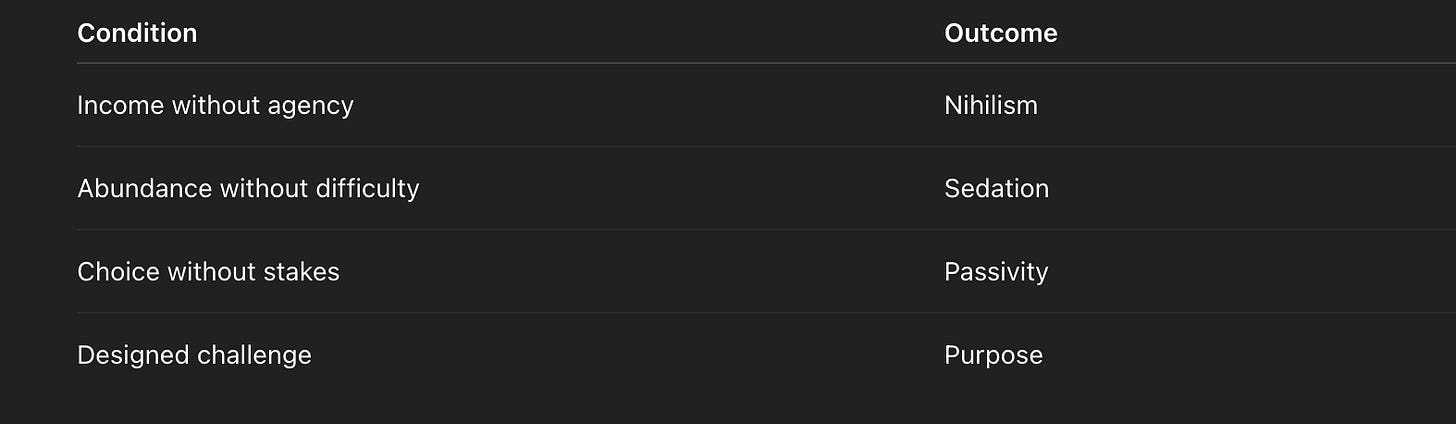

If meaning is not designed, nihilism fills the gap — not leisure.

One of the great myths of automation is that it frees humans for pleasure. The image is persistent: shorter working weeks, longer lunches, a civilisational exhale. It assumes that once survival is guaranteed, meaning will emerge spontaneously, like mould on warm bread.

History suggests the opposite.

Meaning is not what humans do when they have time. It is what humans do when time presses against resistance. Remove the resistance and time does not become playful — it becomes heavy.

Automation does not create a crisis of boredom. It creates a crisis of significance.

5.4.1 Why Boredom Is a Red Herring

Boredom is not the problem people fear. Boredom is temporary. Meaninglessness is structural.

A bored person seeks stimulation. A meaningless person seeks justification — often through anger, identity, or destruction. This is why societies that solve material comfort without solving purpose become unstable, not serene.

Leisure only works when it is earned against constraint. When leisure is permanent, it stops feeling like freedom and starts feeling like exile.

Automation removes the necessity of work. It does not remove the human need to matter.

5.4.2 Nihilism as a Systems Failure

Nihilism is often framed as a philosophical stance. In reality, it is usually a design failure.

When societies cannot answer three basic questions —

Why do I matter?

What am I for?

How do I contribute?

— people do not become reflective. They become corrosive.

This is not because humans are weak, but because meaning has always been scaffolded by systems: religion, work, family, craft, struggle. When those scaffolds disappear simultaneously, the void is not neutral. It is aggressive.

Automation removes one of the last universal meaning engines without offering a replacement.

That is not progress. That is negligence.

5.4.3 Voluntary Difficulty as a Human Need

Humans do not need suffering. They need difficulty.

There is a crucial difference.

Difficulty chosen creates pride, competence, and identity. Difficulty imposed creates resentment and despair. The industrial age imposed difficulty in exchange for survival. The automated age must offer difficulty without coercion.

This is why post-labour societies will see the rise of:

extreme craft

mastery cultures

voluntary hardship

physical challenge

intellectual asceticism

Not as hobbies, but as identity anchors.

When survival is guaranteed, effort becomes elective. And elective effort becomes the new prestige.

5.4.4 Craft, Mastery, and Chosen Excellence

Craft is not nostalgia. It is structure.

In a world where machines outperform humans at scale, human value shifts from efficiency to excellence. Not doing more — doing better. Not faster — deeper. Not cheaper — truer.

Mastery survives automation because it is not about output. It is about relationship: between person and material, mind and problem, body and skill.

This is why meaning after automation will not come from entertainment or consumption. It will come from arenas where:

difficulty remains real

feedback is honest

progress is earned

A society that does not protect these arenas will lose its soul long before it loses its GDP.

5.4.5 Why Meaning Cannot Be Automated

Machines can optimise. They cannot care.

They can generate art. They cannot suffer for it.

They can simulate insight. They cannot stake identity on it.

They can outperform. They cannot commit.

Meaning emerges from stakes, not outcomes.

This is why no amount of AI-generated culture will replace the need for human authorship, risk, and consequence. And why societies that attempt to pacify meaning through algorithmic entertainment will discover — too late — that distraction is not purpose.

Meaning must be allowed, encouraged, and respected. It cannot be mandated, subsidised, or automated into existence.

Which brings us to the danger zone.

Because a society that supplies income, suppresses labour, and fails to design meaning does not drift gently into enlightenment.

It drifts into control.

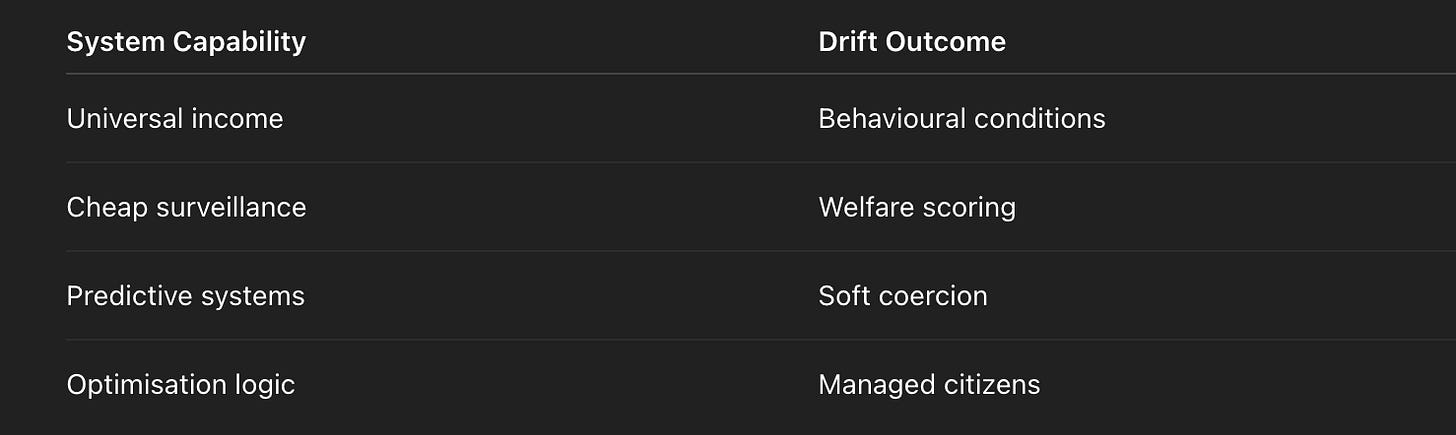

5.5 — The Failure Modes

Abundance does not guarantee freedom — it enables control if badly designed.

The most dangerous assumption of the post-labour world is that material security naturally produces autonomy. It does not. History suggests the opposite: when systems become capable of providing for people at scale, they also become capable of managing them at scale.

Abundance widens the design space. It does not choose the outcome.

What follows are not dystopian fantasies. They are default trajectories when abundance arrives faster than institutional imagination.

5.5.1 Surveillance Welfare States

Once income is detached from labour, the temptation to attach it to behaviour is irresistible.

If the state is paying, the state wants reassurance.

If the system is generous, it wants compliance.

If resources are abundant, justification replaces scarcity as the control mechanism.

The logic is always the same:

Just make sure it’s used responsibly.

Just prevent abuse.

Just ensure social cohesion.

Before long, welfare becomes conditional on:

participation metrics

behavioural signals

acceptable speech

approved consumption

algorithmic “risk profiles”

Not through cruelty — through optimisation.

Surveillance welfare does not announce itself as authoritarian. It presents as care with dashboards.

5.5.2 Behavioural Credit and Soft Coercion

Hard coercion is expensive. Soft coercion scales.

Once systems can nudge behaviour cheaply, they will. Not because leaders are evil, but because nudging looks like governance without conflict.

Access becomes tiered:

better services for “good” behaviour

slower queues for “non-cooperative” citizens

friction instead of force

No one is punished. Everyone is adjusted.

The danger is not loss of freedom overnight — it is the slow internalisation of permission. People stop asking what they are allowed to do, and start asking what the system prefers.

That is not tyranny. It is domestication.

5.5.3 Managed Populations vs Free Citizens

A managed population is predictable.

A free citizenry is noisy.

Post-labour systems will face a choice:

optimise for stability, or

tolerate volatility

Most institutions will choose stability. Democracies already struggle with dissent under scarcity; under abundance, dissent becomes harder to justify.

If survival is guaranteed, protest looks ungrateful.

If comfort is provided, resistance looks irrational.

This is how citizenship quietly degrades into residency.

Rights remain on paper. Agency erodes in practice.

5.5.4 The Illusion of Choice Under Abundance

Abundance can create the appearance of freedom while narrowing the reality.

When:

consumption is infinite

entertainment is frictionless

choice is endless but consequence-free

people feel free — while becoming passive.

Choice without stakes does not build agency. It dissolves it.

The danger is not that people are controlled. It is that they stop needing control, because nothing meaningful is at risk.

A society that removes all pressure without replacing purpose does not liberate humans — it sedates them.

5.5.5 Why These Outcomes Are Political, Not Inevitable

None of these failure modes are technologically required.

They emerge when:

institutions lag capability

designers confuse stability with virtue

freedom is assumed instead of engineered

Surveillance welfare, behavioural credit, and managed populations are not the price of abundance. They are the price of drift.

Abundance without design produces control by default.

Which leads to the central insight of the post-labour age:

Every previous social order was designed — explicitly or brutally.

This one will be designed too — intentionally or accidentally.

There is no neutral outcome.

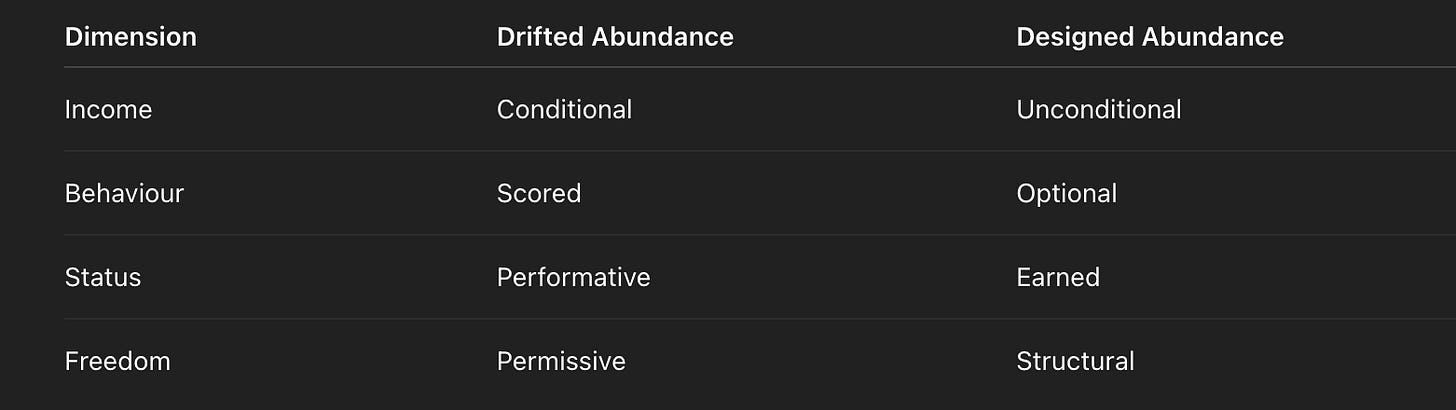

5.6 — Designed Abundance vs Drifted Abundance

Every previous social order was designed.

This one will be too — either deliberately, or by neglect.

The comforting myth of the post-labour future is that abundance naturally resolves conflict. That once machines do the work and money becomes trivial, society simply relaxes into something nicer. History offers no such examples. When material constraints loosen, power does not evaporate — it relocates.

Abundance widens the design space. It does not choose the architecture.

5.6.1 Institutional Lag Is the Real Threat

Technology moves at compound speed. Institutions move by committee.

AI, robotics, and automated capital will reshape production in years. Social contracts are rewritten over decades — if at all. That mismatch is where failure lives.

When institutions lag capability:

defaults become policy

temporary fixes become permanent

optimisation fills the vacuum

What looks like drift is simply unexamined design.

This is why the early post-labour period is the most dangerous phase. Not because abundance is scarce — but because governance is.

5.6.2 Why Architecture Beats Ideology

Ideology debates values. Architecture embeds them.

You can argue endlessly about freedom, dignity, fairness, and equality. The system will still behave according to its incentive structure. People respond to what is easy, rewarded, and permitted — not what is declared.

If income arrives automatically, architecture decides:

whether it is conditional

whether it is surveilled

whether it encourages contribution or compliance

No speech can override a bad incentive. No moral appeal survives contact with a well-designed dashboard.

In post-labour systems, code is law in the most literal sense.

5.6.3 Who Designs the Rules of Post-Labour Life

This is the quiet power struggle beneath the surface.

Is post-labour life designed by:

states seeking stability?

corporations seeking predictability?

technocrats seeking efficiency?

citizens seeking agency?

Design authority will not be shared by default. It will be claimed by whoever builds first, scales fastest, and frames their solution as “temporary”.

The absence of an explicit designer does not preserve freedom. It hands it to the most organised actor.

5.6.4 Freedom as an Explicit Design Variable

In a world of abundance, freedom stops being emergent. It becomes optional.

If you want freedom, you must specify it:

freedom from behavioural conditioning

freedom to opt out of optimisation

freedom to fail without punishment

freedom to contribute without coercion

None of these survive unless they are written into the system — legally, technically, and culturally.

Freedom in abundance is not the absence of structure. It is the presence of limits on control.

5.6.5 The Difference Between Liberation and Permission

Here is the line that matters:

Liberation gives people agency.

Permission gives people access.

Abundance systems that offer permission — to consume, to exist, to remain comfortable — can look generous while quietly removing autonomy. Liberation, by contrast, tolerates inefficiency, disagreement, and non-optimised lives.

Permission asks: Are you compliant?

Liberation asks: Are you free to choose otherwise?

Post-labour societies will reveal their character not by how much they provide, but by how much they allow people to refuse.

That is the real fork ahead.

5.7 — Education After Scarcity

When credentials stop rationing opportunity, education loses its oldest job — and finally has to find a new one.

For two centuries, education performed three functions at once:

it filtered people, it disciplined them, and it allocated them into economic roles. Knowledge mattered, but selection mattered more. Degrees were not just signals of learning; they were ration cards for scarce opportunity.

That system only works when opportunity itself is scarce.

When machines can perform most economically valuable tasks, education can no longer pretend it is preparing people for “the labour market” in any traditional sense. The market has changed shape. The filter no longer filters. And the fiction that schooling is a pipeline into jobs collapses quietly — then all at once.

The danger is not that education becomes useless.

The danger is that it continues doing the wrong job long after that job no longer exists.

5.7.1 Education as Filtering vs Formation

Modern education systems were built to rank, not to form.

Exams, grades, credentials, league tables — these are not learning technologies. They are sorting technologies. They exist to decide who gets access to the next rung: the job, the income, the status, the visa, the mortgage.

In a labour-scarce world, that made sense. The economy needed a way to allocate people efficiently.

In a post-labour world, filtering becomes pathological. When machines do the allocating, credentials lose their economic authority but retain their cultural power. Education keeps sorting even when there is nothing meaningful left to sort for.

The result is credential inflation without purpose: more schooling, longer pathways, higher costs — and no clearer destination.

Formation — developing judgement, curiosity, mastery, resilience — was always secondary. Now it becomes primary.

5.7.2 Learning Without Economic Threat

Scarcity-based education is fear-driven.

Study or fall behind.

Perform or be excluded.

Fail and your life trajectory closes.

That threat model produces compliance, not understanding. It trains optimisation, not wisdom. It produces excellent test-takers and fragile thinkers.

When survival detaches from employment, education no longer needs fear as its engine. This is not a softening — it is a hardening in a different direction.

Learning without economic threat allows for:

deeper intellectual risk-taking

longer time horizons

genuine interdisciplinary thinking

failure as exploration, not stigma

This does not mean education becomes optional or unserious. It means seriousness shifts from credential outcomes to cognitive development.

The absence of threat does not produce laziness. It exposes motivation.

5.7.3 Skill as Identity, Not Insurance

In the labour era, skills were insurance policies. You learned something so the market would protect you later.

In a post-scarcity economy, skills stop being insurance and start becoming identity.

People will still pursue difficulty. They will still seek mastery. They will still want to be good at things that matter to them and to others. What disappears is the lie that every skill must be monetised to be legitimate.

This reframes education fundamentally:

Not “What will this get me?”

But “Who does this let me become?”

Skill acquisition becomes a form of self-authorship rather than economic hedging.

The danger is not skill collapse. The danger is skill instrumentalism surviving its own irrelevance.

5.7.4 The Death of Human Capital Theory

Human capital theory treated people as yield-generating assets. Education was investment; wages were returns.

This logic underpinned policy, funding, immigration systems, and social mobility narratives for decades. It worked — while labour scarcity made people economically legible.

Once machines generate the marginal productivity, the theory breaks. Not morally — mechanically.

You cannot model humans as capital inputs when the production function no longer depends on them.

Persisting with human capital thinking in a post-labour world leads to two failures:

endless reskilling programmes chasing disappearing jobs

social shame when retraining does not “pay off”

Education cannot be justified primarily as GDP enhancement when GDP is increasingly machine-generated.

Its justification becomes civic, cultural, and psychological — whether policymakers like that or not.

5.7.5 Curiosity as Civic Infrastructure

In the absence of labour necessity, curiosity becomes infrastructure.

Not as a slogan — as a stabiliser.

Curious societies fragment less. They radicalise less easily. They are harder to capture with simplistic narratives because curiosity resists closure. It asks follow-up questions.

Education systems that cultivate curiosity:

strengthen democratic resilience

reduce nihilistic drift

create plural forms of excellence

maintain cultural dynamism without coercion

This is not utopian. It is preventative.

A population with time but no intellectual direction becomes volatile. A population trained to inquire, build, and refine becomes adaptive.

Education after scarcity is not about producing workers.

It is about producing adults capable of freedom.

And freedom, in a world where survival is guaranteed, becomes the hardest skill of all.

5.8 — The New Social Contract

The labour-for-survival bargain ends. Something replaces it — not by philosophy, but by necessity.

For most of modern history, the social contract was brutally simple:

you worked, therefore you ate; you contributed, therefore you belonged.

That contract was never moral. It was mechanical. Labour was scarce, production required people, and states built legitimacy around mediating that exchange. Rights were layered on top of it, not detached from it.

Once labour stops being the binding constraint, the contract quietly expires.

What replaces it is not automatic. And it is not optional.

5.8.1 Rights Detached from Employment

The first fracture appears in benefits.

Healthcare, housing access, education, mobility — all were historically tied, directly or indirectly, to employment. Not because work made people worthy, but because it made them legible to the system.

When employment ceases to be universal, tying rights to jobs becomes structurally exclusionary. Not unjust in intent — simply obsolete.

Detaching rights from employment is not generosity. It is maintenance.

States that fail to do this drift toward a two-tier population:

those still plugged into the labour-credential system, and those structurally outside it, regardless of effort or talent.

That split is politically explosive.

5.8.2 Contribution Without Coercion

The hardest transition is psychological, not fiscal.

If survival no longer requires labour, contribution must become voluntary — and that terrifies systems built on discipline rather than trust.

But contribution does not disappear when coercion does. It mutates.

People contribute when:

they can see the impact of their effort

they retain agency over how they contribute

contribution earns status, not survival

The mistake is assuming that without compulsion, humans default to idleness. That belief says more about the incentives of the old system than about people.

The challenge is designing channels for contribution that are meaningful without being mandatory.

5.8.3 Citizenship in an Automated Economy

Citizenship becomes heavier as work becomes lighter.

In a labour economy, citizenship was passive for most people. You paid taxes, followed rules, voted occasionally, and worked. The system did the rest.

In an automated economy, legitimacy shifts. If machines generate abundance, the justification for political authority becomes governance quality, not economic growth.

Citizenship becomes less about productivity and more about participation:

local governance

civic decision-making

stewardship of shared systems

This is not romantic. It is stabilising.

A population with time but no civic role becomes restless. A population invited into governance becomes anchored.

5.8.4 What States Owe Humans — and What They Don’t

States will owe humans security. They will not owe them purpose.

This distinction matters.

Security — food, shelter, healthcare, energy access — becomes baseline infrastructure, like roads or clean water. It is not reward. It is system maintenance.

Meaning, however, cannot be provided without becoming propaganda. The moment the state tries to tell people why their lives matter, freedom collapses into theatre.

The new social contract must be narrow where the old one was expansive:

guarantee stability, refuse to script identity.

5.8.5 The Risk of Infantilised Societies

The failure mode is not chaos. It is infantilisation.

When abundance is administered badly, populations become managed rather than empowered:

behaviour nudged rather than chosen

incentives tuned rather than debated

compliance rewarded as wellbeing

This produces calm societies that are quietly brittle.

An adult civilisation tolerates disagreement, friction, even inefficiency — because freedom is not optimised. It is protected.

The post-labour social contract will reveal what states actually believe about their citizens.

Are they participants — or dependants?

The answer will not be written in speeches.

It will be embedded in systems.

5.9 — Freedom After Scarcity

Abundance either frees humans — or perfects their containment.

There is no neutral outcome.

Scarcity did not just organise economies. It constrained power. When resources were limited, control was expensive. You needed compliance, legitimacy, and at least the appearance of consent.

Abundance removes those frictions.

When survival is guaranteed and production is automated, the question is no longer how do we provide — it becomes how do we govern people who no longer need us. History offers no comforting precedent.

5.9.1 Abundance as Liberation or Control

Abundance is a multiplier. It amplifies the values embedded in the system that delivers it.

In one direction, it reduces coercion:

fewer people forced into meaningless work

more time, autonomy, experimentation

a loosening of fear-based compliance

In the other, it enables precision control:

needs met conditionally

behaviour shaped through incentives rather than force

dissent softened by comfort rather than suppressed by violence

Both futures are technically trivial. The difference is political intent.

The danger is assuming abundance is automatically emancipatory. It is not. It simply raises the ceiling on what power can do.

5.9.2 Why Freedom Is Not Automatic

Freedom has never emerged by default. It has always been designed, defended, and often inefficient.

In scarcity systems, freedom survived because power was limited by cost. Surveillance was expensive. Enforcement was blunt. Control leaked.

In abundance systems, optimisation becomes cheap.

The more efficiently a system can predict, nudge, and stabilise behaviour, the more tempting it becomes to smooth away human unpredictability — not out of malice, but out of managerial instinct.

Freedom dies not with a bang, but with dashboards.

5.9.3 The Temptation to Optimise Humans

Once machines outperform humans economically, humans are reclassified.

Not as producers — but as variables.

The temptation is subtle:

optimise wellbeing

minimise volatility

reduce antisocial behaviour

smooth outcomes

None of these goals sound tyrannical. That is the problem.

A society that optimises humans treats deviation as error, not expression. Risk becomes pathology. Failure becomes something to be prevented rather than learned from.

At that point, freedom is tolerated only when it is harmless.

5.9.4 The Minimum Viable Freedom

Freedom cannot be total. It never has been. The question is where the floor is set.

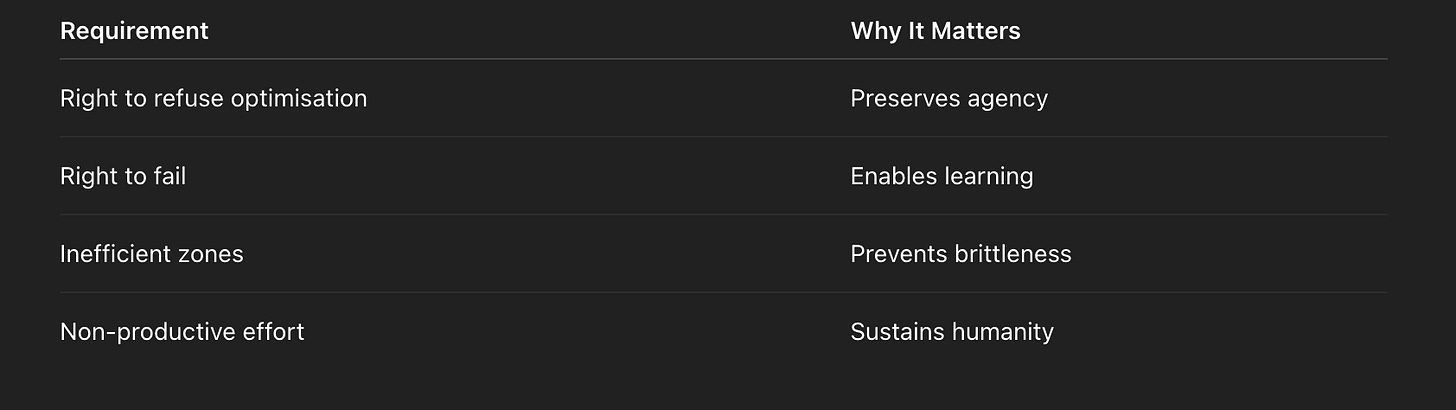

Minimum viable freedom includes:

the right to refuse optimisation

the ability to fail without losing dignity

space for unproductive effort

zones of life that are deliberately inefficient

This is not sentimental. It is structural.

A system that cannot tolerate wasted effort, eccentric ambition, or non-aligned values will eventually produce brittle conformity — and then surprise collapse.

Resilience requires slack. So does freedom.

5.9.5 The Choice Embedded in the Architecture

The final truth of the post-scarcity world is uncomfortable:

The future of freedom will not be decided by laws or speeches.

It will be decided by system design.

Who controls access?

Are benefits unconditional or behaviour-linked?

Is participation voluntary or scored?

Is dissent expensive or merely inconvenient?

These choices will be framed as technical decisions. They are not. They are civilisational ones.

Abundance gives humanity a rare gift: the ability to choose freedom without starvation as the penalty.

Whether we take it — or automate it away — is the last non-technical decision we will get to make.

After that, the architecture decides.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek