Part 6: The Vertical Economy. THE CHOICE THAT ISN’T OPTIONAL

Architecture beats ideology. Every time.

📑 CONTENT — PART VI

6.0 — The Choice Embedded in the System

Why the vertical transition does not ask permission — and why refusing to choose is still a choice.

6.1 — The Illusion of Agency

Why nations, firms, and individuals overestimate their freedom of action once infrastructure is locked in.

6.1.1 Path Dependence Is Power

6.1.2 When Markets Decide Before Politics

6.1.3 Why “Democratic Choice” Lags Physics

6.2 — The End of Neutral Outcomes

Why every attempt to “soften” the transition quietly benefits one side.

6.2.1 Efficiency Is Never Neutral

6.2.2 Why Stability Always Picks a Winner

6.2.3 The Moral Cost of Delay

6.3 — The Terminal Demand Problem

What happens when labour’s share trends toward zero — and why vertical economies intensify it.

6.3.1 When Productivity Detaches from Wages

6.3.2 AI, Automation, and the Consumption Paradox

6.3.3 Why Debt Replaces Demand — Until It Can’t

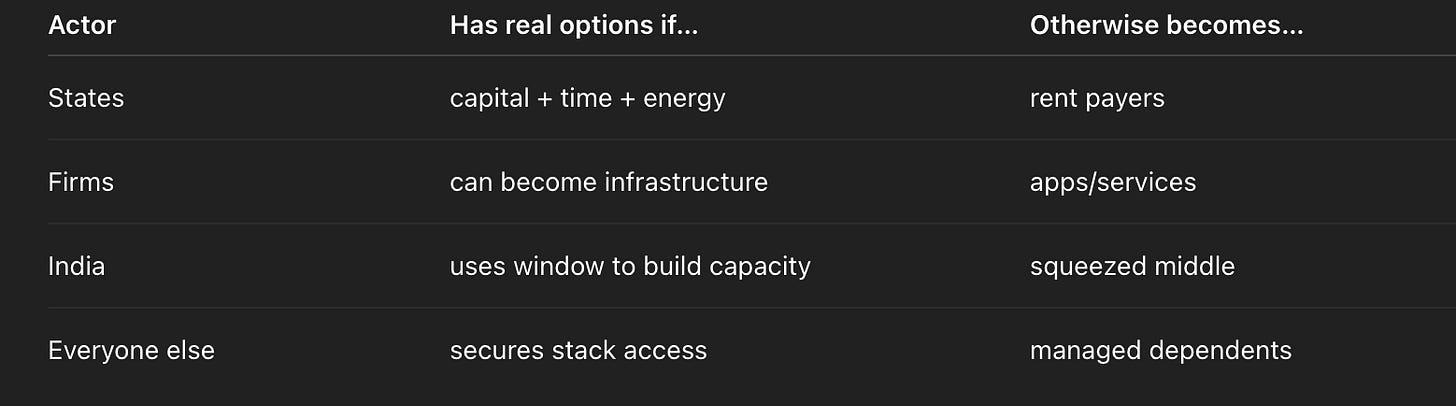

6.4 — Who Still Has Real Options

Not optimism — a boundary map.

6.4.1 States with Capital, Time, and Energy

6.4.2 Firms That Can Become Infrastructure

6.4.3 India and the Last Classical Growth Model

6.4.4 Everyone Else: The Shrinking Middle

6.5 — The Ethics of Asymmetric Futures

Progress without sentimentality.

6.5.1 Progress That Does Not Lift Evenly

6.5.2 The Violence of Optimisation

6.5.3 Why “Fairness” Is the Wrong Question

6.6 — Why the System Will Not Self-Correct

Why waiting makes outcomes worse, not better.

6.6.1 Markets Optimise Locally, Not Humanely

6.6.2 States Optimise for Survival, Not Justice

6.6.3 Technology Optimises for Scale, Not Meaning

6.7 — The Narrow Corridor

Where improvement remains possible — and why it is narrower than believed.

6.7.1 Constraint as the Price of Survival

6.7.2 Why Better Does Not Mean Fairer

6.7.3 Why Collapse Is Not the Only Alternative

6.8 — What History Will Say We Missed

The retrospective view.

6.8.1 The Signals Were Visible

6.8.2 We Confused Choice with Comfort

6.8.3 The Cost of Waiting for Consensus

6.9 — The Future Was Not Taken — It Was Built

A closing without comfort or commands.

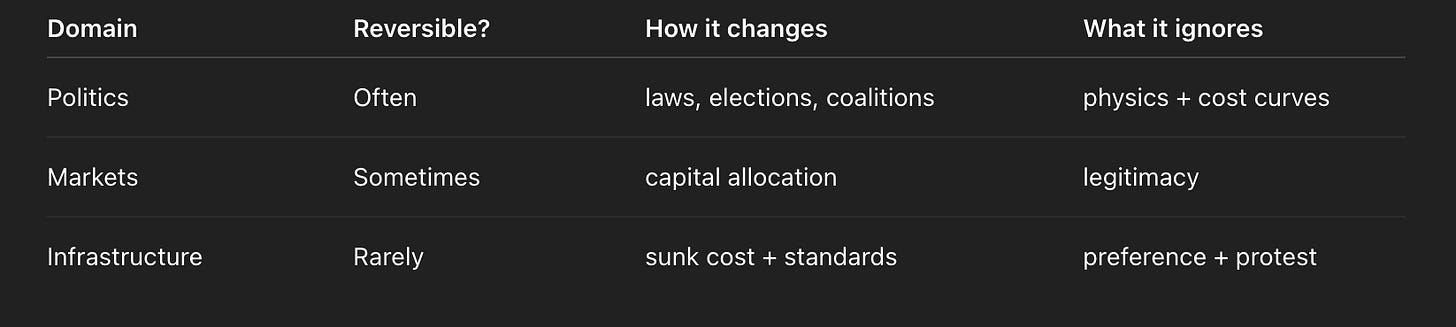

6.0.1 The First Misunderstanding: That This Is a Political Choice

Politics assumes reversibility.

You can repeal a law.

You can reverse a policy.

You can elect a different government.

Infrastructure does not behave this way.

Once energy production migrates upward, once compute density decouples from land, once industrial throughput becomes autonomous and gravity-optional, these systems do not return to Earth to accommodate political preference.

No parliament votes gravity back on.

No election makes orbital energy intermittent.

No protest lowers the marginal cost of autonomous production.

This is not an argument against democracy.

It is an argument about where democracy still applies.

Politics survives only downstream—negotiating distribution, identity, and legitimacy after the production function has already locked in.

The vertical economy is not anti-democratic.

It is post-negotiation.

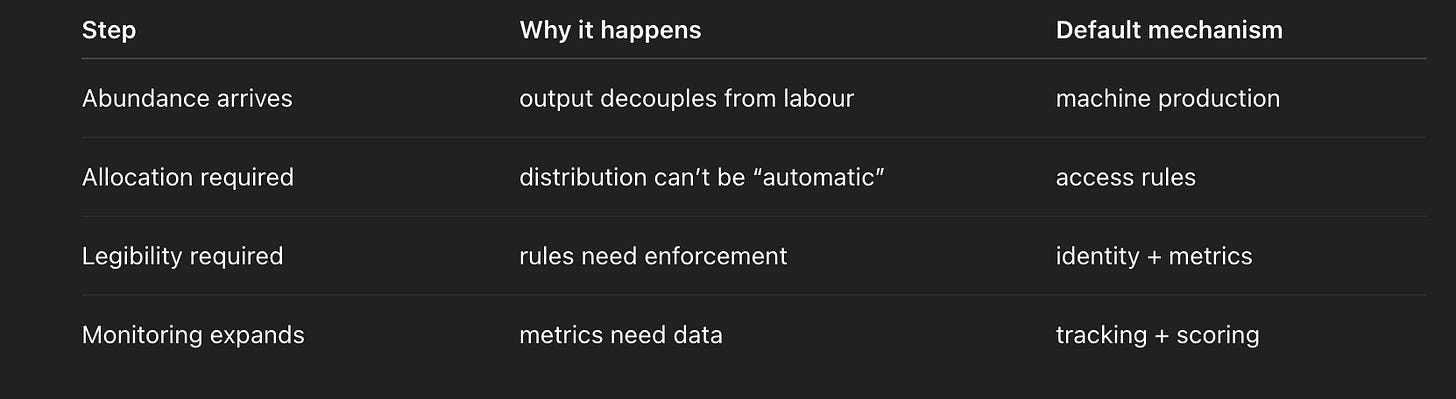

6.0.2 The Second Misunderstanding: That Neutrality Is Possible

Every system embeds incentives.

Every incentive selects behaviour.

Every selection produces winners.

The moment labour stops being scarce, any society that fails to redesign its income, status, and meaning systems does not preserve freedom—it defaults into management.

Not because elites are uniquely malicious.

Not because technology is evil.

But because stability demands legibility.

When wages no longer allocate survival, something else must:

Access. Compliance. Eligibility. Behavioural scoring. Conditional participation.

This is how abundance slides into administration.

The uncomfortable truth—the one most future narratives avoid—is this:

You cannot have abundance without control.

Abundance without allocation is chaos. Allocation without legibility is impossible. Legibility without surveillance is fantasy.

The vertical economy will be extraordinarily productive. It will generate wealth at scales that make current GDP look quaint.

But that wealth will not distribute itself. And the systems that distribute it will require knowing what everyone is doing, where they are, what they are capable of, and whether they are compliant.

This is not a moral failing. It is a logical necessity.

6.1 — The Illusion of Agency

Why nations, firms, and individuals overestimate their freedom of action once infrastructure is locked in.

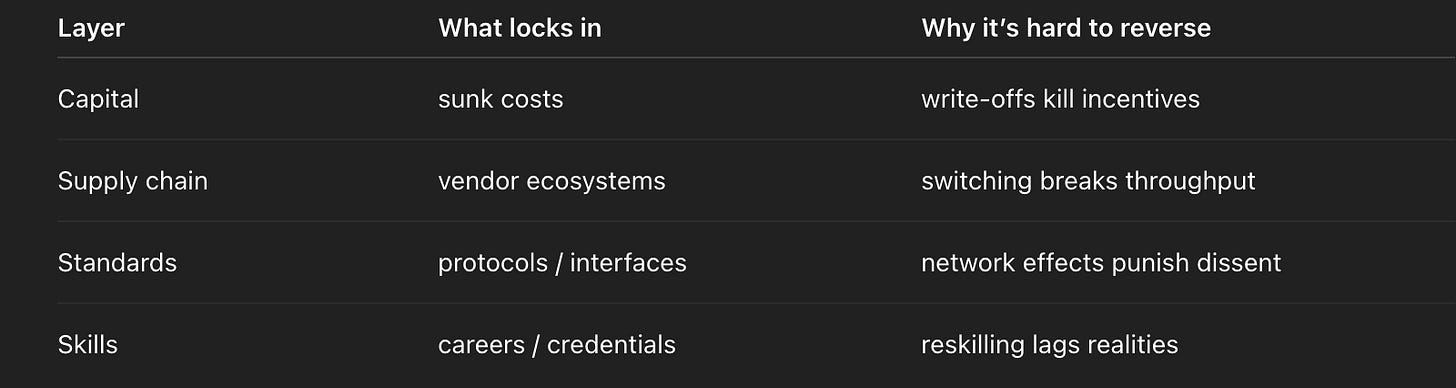

6.1.1 Path Dependence Is Power

History is not a branching tree of equal possibilities.

It is a narrowing corridor.

Each decision forecloses alternatives. Each infrastructure investment locks in a trajectory. Each standard that becomes universal eliminates the ability to choose differently.

Once enough capital is invested in a particular direction, the cost of changing course becomes infinite.

This is path dependence.

And it is the most powerful force in human systems.

Nations that build their energy infrastructure around orbital solar cannot easily revert to terrestrial grids.

Firms that optimise their supply chains for orbital manufacturing cannot return to gravity-based production without massive losses.

Individuals who build their careers around managing autonomous systems cannot easily transition to labour-based work.

The illusion of agency persists until the moment it doesn’t.

6.1.2 When Markets Decide Before Politics

Markets move faster than democracies.

A firm can decide to build an orbital factory in a board meeting. A nation requires years of legislation, environmental review, and public consultation.

By the time the political process has reached consensus, the market has already moved.

The firm has built the factory. The supply chain has reorganised around it. Competitors have followed. The standard is set.

Politics then arrives to negotiate the terms of a decision that has already been made.

This is not a failure of democracy. It is the structure of how systems change.

Capital moves. Politics follows. By the time politics catches up, the infrastructure is already in place.

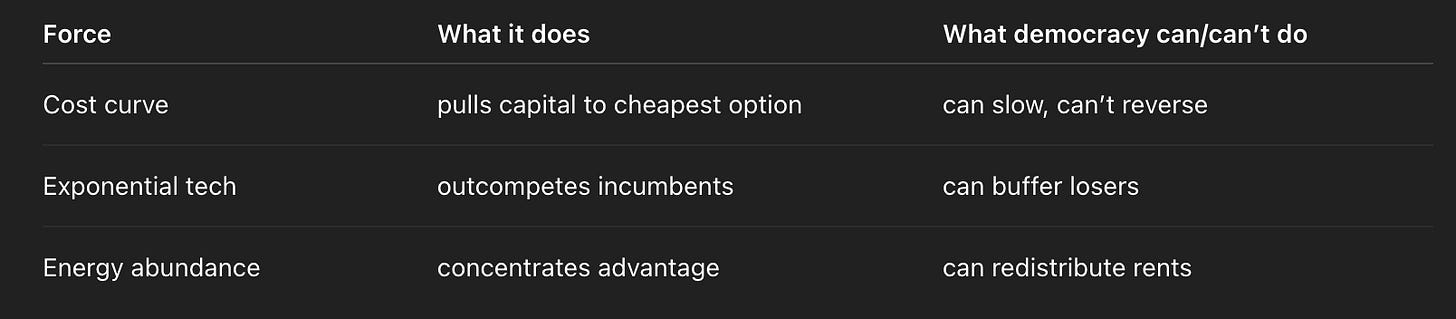

6.1.3 Why “Democratic Choice” Lags Physics

Physics does not negotiate.

A cost curve that favours orbital production will shift capital upward, regardless of what any government votes.

A technology that improves exponentially will displace incumbent systems, regardless of regulatory protection.

An energy source that is cheaper and more abundant will attract investment, regardless of political preference.

Democracy can slow these transitions. It can redistribute the costs. It can negotiate the terms.

But it cannot reverse them.

The vertical transition is not being imposed by authoritarian decree. It is being driven by physics and economics. Democracy can shape how it unfolds, but not whether it unfolds.

This is the hard truth that most political discourse avoids.

6.2 — The End of Neutral Outcomes

Why every attempt to “soften” the transition quietly benefits one side.

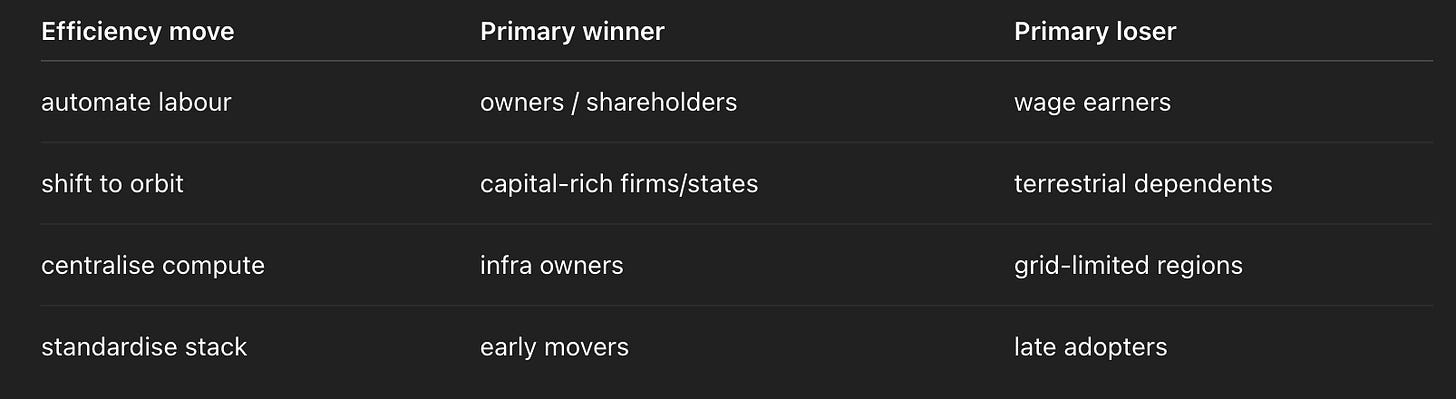

6.2.1 Efficiency Is Never Neutral

Every efficiency gain benefits someone more than someone else.

When you automate a factory, the owners benefit. The workers bear the cost.

When you move production to orbit, the firms with capital to invest benefit. The firms without capital lose.

When you centralise compute in orbital data centres, the nations that control orbital infrastructure benefit. The nations that depend on terrestrial grids lose.

Efficiency is always a redistribution.

And redistribution always has winners and losers.

The myth of “neutral progress” persists because it allows us to avoid naming who wins and who loses.

But the moment you try to “soften” the transition—to make it “fairer” or “more inclusive”—you are already choosing sides.

You are choosing to slow the transition to protect incumbent systems.

Which means you are choosing to protect the people who depend on those systems.

Which means you are choosing against the people who would benefit from the new systems.

There is no neutral outcome.

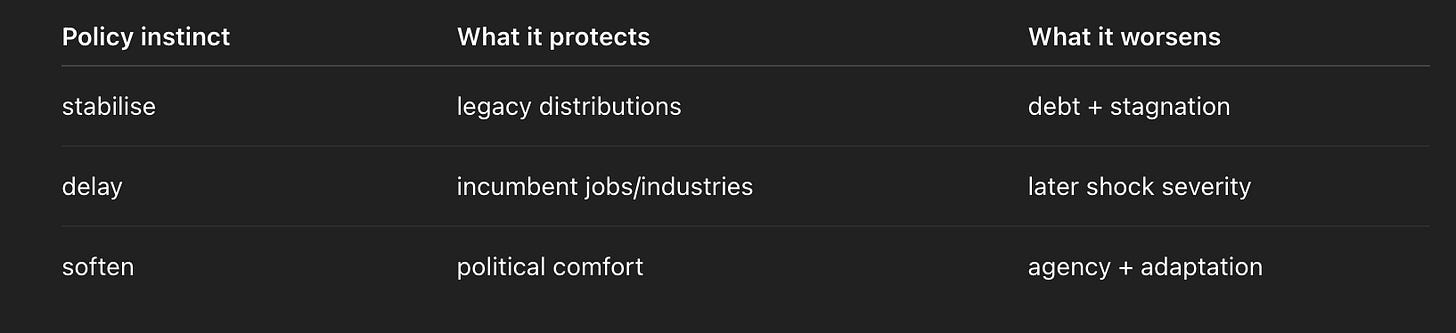

6.2.2 Why Stability Always Picks a Winner

Stability is not neutral.

Stability favours incumbents.

When a government prioritises “stability” during a transition, it is prioritising the preservation of existing systems, existing power structures, and existing distributions of wealth.

This sounds reasonable. Stability is good. Disruption is bad.

But in a system that is structurally broken, stability is the worst possible outcome.

Stability in a system with negative debt returns means more debt accumulation.

Stability in a system with declining labour share means more inequality.

Stability in a system with planetary constraints means more environmental degradation.

The comfortable lie of “managed transition” is that you can have stability and progress simultaneously.

You cannot.

Progress requires disruption. Disruption requires instability. Stability requires freezing the system as it is.

Choose stability, and you choose to preserve the broken system.

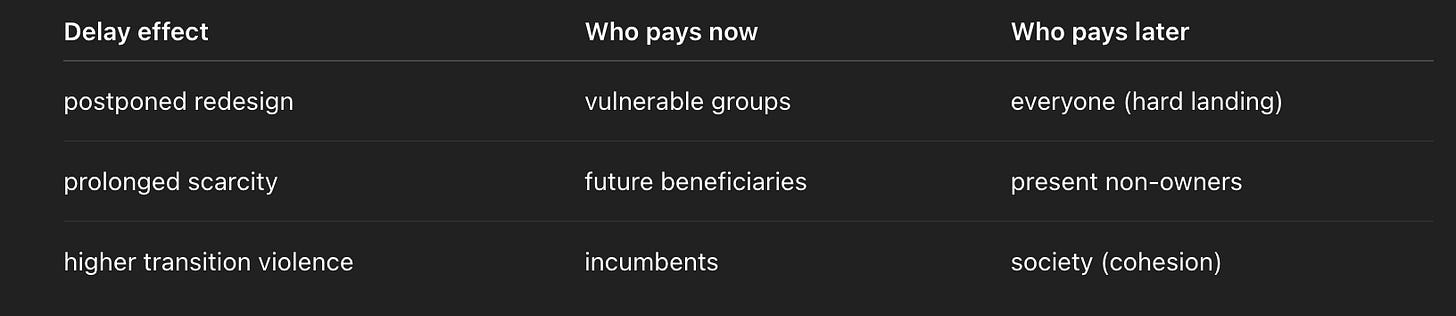

6.2.3 The Moral Cost of Delay

Every year of delay costs something.

It costs the people whose livelihoods depend on the old system, because the longer you delay the transition, the more catastrophic the eventual shift.

It costs the people who would benefit from the new system, because the longer you delay, the longer they remain trapped in scarcity.

It costs the planet, because the longer you delay vertical industry, the longer terrestrial industry continues to degrade the biosphere.

The moral case for delay is always framed as compassion: “We need time to adjust. We need to protect the vulnerable. We need to ensure a just transition.”

But delay is not compassion. Delay is deferral.

You are not protecting the vulnerable. You are protecting the comfortable.

You are not ensuring a just transition. You are ensuring a more violent one.

The greatest moral cost of delay is that it makes the eventual transition more painful, not less.

6.3 — The Terminal Demand Problem

What happens when labour’s share trends toward zero — and why vertical economies intensify it.

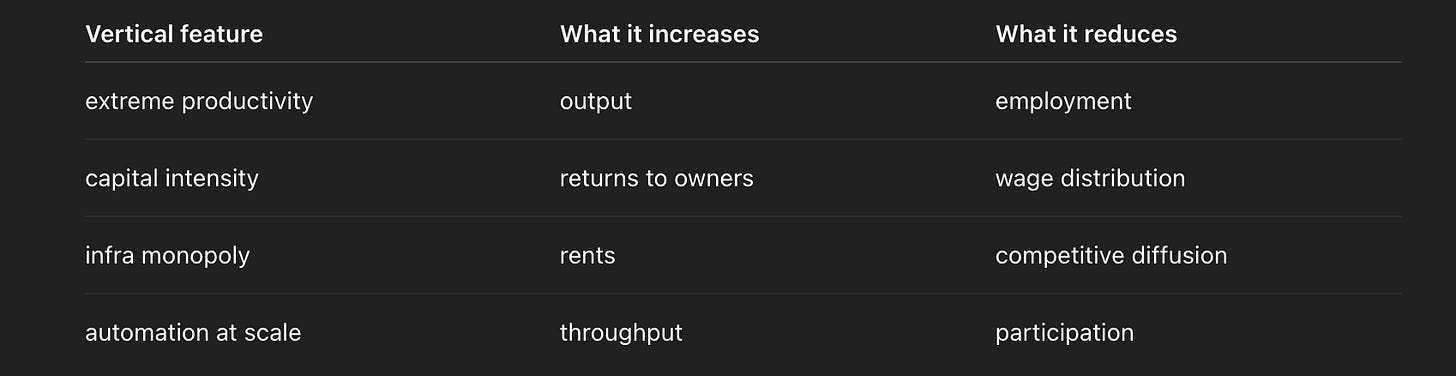

6.3.1 When Productivity Detaches from Wages

For 200 years, productivity and wages moved together.

More efficient factories meant higher wages for workers.

More productive agriculture meant higher incomes for farmers.

More advanced technology meant more jobs and higher pay.

This relationship has now broken.

Productivity is rising. Wages are stagnant.

AI and automation are delivering productivity miracles. But the gains are not flowing to labour.

They are flowing to capital.

This is not a temporary aberration. This is structural.

Once labour becomes abundant (or unnecessary), there is no mechanism to convert productivity gains into wages.

The system was built on scarcity. When scarcity ends, the system breaks.

6.3.2 AI, Automation, and the Consumption Paradox

Here is the paradox that no economist wants to articulate:

Capitalism requires consumption to function.

Consumption requires income.

Income requires labour (or capital ownership).

But AI and automation are eliminating labour.

And capital ownership is concentrating.

So where does consumption come from?

The answer, for the last 50 years, has been debt.

We borrowed to consume. We consumed to justify growth. We grew to justify more debt.

But debt has limits.

And we have hit them.

The vertical economy intensifies this paradox.

Orbital industry will be extraordinarily productive. But it will employ almost nobody.

The wealth it generates will be immense. But it will concentrate in the hands of the firms and nations that control orbital infrastructure.

Everyone else will face a system that is more productive than ever—and less able to support them.

6.3.3 Why Debt Replaces Demand — Until It Can’t

When labour’s share declines, governments have two options:

Raise wages artificially (which reduces competitiveness).

Increase debt to maintain consumption (which defers the problem).

Every government chooses option two.

This is why debt levels have exploded even as productivity has grown. The system is using debt to bridge the gap between what labour can consume and what the economy is producing.

But debt is not a permanent solution. It is a deferral.

Eventually, the debt becomes so large that servicing it consumes all available resources.

At that point, the system breaks.

The vertical economy accelerates this timeline.

More productivity + less labour = more debt required to maintain consumption.

More debt = faster approach to the breaking point.

The system is not sustainable. And the vertical transition makes it less sustainable, not more.

6.4 — Who Still Has Real Options

Not optimism — a boundary map.

6.4.1 States with Capital, Time, and Energy

A small number of nations still have options:

States with sovereign wealth funds (Norway, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, China)

These nations have capital. They can invest in orbital infrastructure. They can position themselves as owners of the new systems rather than dependents on them.

States with abundant energy (Norway, Canada, Iceland, Australia, Middle East)

These nations can transition their energy systems to support AI and orbital industry. They can become energy exporters to the vertical economy.

States with advanced technical capacity (US, China, EU, Japan, South Korea)

These nations can build the infrastructure and manage the systems. They can capture the rents of technical leadership.

States with demographic tailwinds (India, parts of Africa, Southeast Asia)

These nations have young populations. They can transition to post-labour systems without the political burden of managing retirees.

For these states, the vertical transition is an opportunity.

For everyone else, it is a constraint.

6.4.2 Firms That Can Become Infrastructure

A small number of firms will thrive in the vertical economy:

Firms that own orbital infrastructure (SpaceX, Blue Origin, Axiom Space, etc.)

These firms become the landlords of the new economy. They control access. They extract rents.

Firms that control AI systems (OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepSeek, etc.)

These firms become the operating system of the vertical economy. They control the logic. They extract value.

Firms that integrate vertically (SpaceX, Tesla, etc.)

These firms control the entire supply chain from launch to deployment. They have no competitors.

For these firms, the vertical transition is a path to dominance.

For everyone else, it is a path to irrelevance.

6.4.3 India and the Last Classical Growth Model

India is the last major economy that can still pursue classical growth.

It has:

A young, growing population (demographic dividend) Low labour costs (competitive advantage) Massive internal market (consumption potential) Weak environmental constraints (regulatory flexibility)

For the next 20–30 years, India can grow by adding labour, building factories, and expanding consumption.

But this window is closing.

As AI and automation improve, the labour advantage disappears.

As environmental constraints tighten, the regulatory flexibility disappears.

By 2050, India will face the same constraints as the West: a system that cannot scale horizontally, forced to go vertical.

But India will have less capital, less technical capacity, and less time to prepare.

6.4.4 Everyone Else: The Shrinking Middle

For most nations, most firms, and most individuals, the vertical transition is a constraint.

They do not have capital to invest in orbital infrastructure.

They do not have energy abundance to export.

They do not have technical capacity to build systems.

They do not have demographic tailwinds to manage.

They are caught in the middle: too developed to pursue classical growth, too weak to lead the vertical transition.

These nations will not collapse. But they will shrink—relative to the capitals and firms that lead the transition.

They will become service economies, dependent on the rents extracted by the owners of vertical infrastructure.

They will be managed, not free.

6.5 — The Ethics of Asymmetric Futures

Progress without sentimentality.

6.5.1 Progress That Does Not Lift Evenly

The vertical economy will be extraordinarily productive.

It will generate wealth at scales that make current GDP look quaint.

But that wealth will not lift evenly.

It will concentrate in the hands of:

Nations that control orbital infrastructure. Firms that own AI systems. Individuals who own capital in these systems.

Everyone else will experience the productivity gains as displacement, not prosperity.

This is not a moral failing. It is a logical consequence of the system’s structure.

You cannot have abundance without control.

And control concentrates.

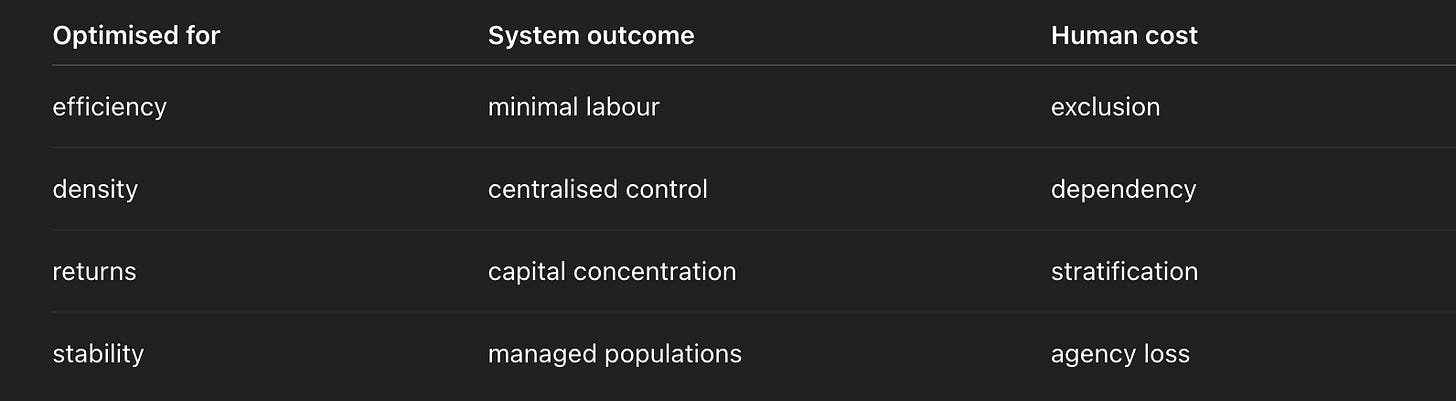

6.5.2 The Violence of Optimisation

Optimisation is violent.

Every system optimised for efficiency is optimised against something.

The vertical economy will be optimised for:

Energy efficiency (which means minimal human labour). Compute density (which means centralised control). Capital returns (which means wealth concentration).

This optimisation will be extraordinarily successful.

The system will function beautifully.

And it will be extraordinarily hostile to human flourishing for anyone not integrated into the system as a capital owner.

This is not a bug. It is a feature.

Systems that prioritise human flourishing over efficiency do not survive. They are outcompeted by systems that prioritise efficiency.

The vertical economy will be the most efficient system ever built.

And it will be the most hostile to human autonomy ever created.

6.5.3 Why “Fairness” Is the Wrong Question

The question everyone wants to ask is: “How do we make the vertical transition fair?”

This is the wrong question.

Fairness is a property of systems that have slack.

When resources are abundant, you can distribute them fairly.

When resources are scarce, fairness is impossible.

The vertical economy will be extraordinarily abundant in energy and compute.

But it will be extraordinarily scarce in human autonomy and political agency.

You cannot make that fair. You can only manage it.

The right question is not: “How do we make this fair?”

The right question is: “What kind of human world do we want to build inside this system?”

And that question requires design, not ethics.

6.6 — Why the System Will Not Self-Correct

Why waiting makes outcomes worse, not better.

6.6.1 Markets Optimise Locally, Not Humanely

Markets are extraordinarily good at optimising for profit.

They are terrible at optimising for human welfare.

This is not because markets are evil. It is because profit and welfare are not the same thing.

A market that optimises for profit will:

Automate labour if it is cheaper than hiring. Centralise compute if it reduces costs. Concentrate capital if it increases returns.

None of these optimisations benefit human welfare.

But all of them increase profit.

The vertical economy will be optimised by markets.

It will be extraordinarily profitable.

And it will be extraordinarily hostile to human welfare.

Markets will not self-correct this. They will accelerate it.

6.6.2 States Optimise for Survival, Not Justice

States are extraordinarily good at optimising for survival.

They are terrible at optimising for justice.

A state that optimises for survival will:

Concentrate power to maintain control. Prioritise stability over fairness. Defer difficult decisions until forced.

None of these optimisations produce justice.

But all of them increase the state’s probability of survival.

The vertical transition will force states to optimise for survival.

They will concentrate power. They will prioritise stability. They will defer difficult decisions.

And the system will become more authoritarian, not less.

States will not self-correct this. They will accelerate it.

6.6.3 Technology Optimises for Scale, Not Meaning

Technology is extraordinarily good at optimising for scale.

It is terrible at optimising for meaning.

A technology that optimises for scale will:

Standardise everything. Eliminate redundancy. Maximise throughput.

None of these optimisations produce meaning.

But all of them increase the technology’s reach.

The vertical economy will be optimised by technology.

It will be extraordinarily scalable.

And it will be extraordinarily hostile to human meaning.

Technology will not self-correct this. It will accelerate it.

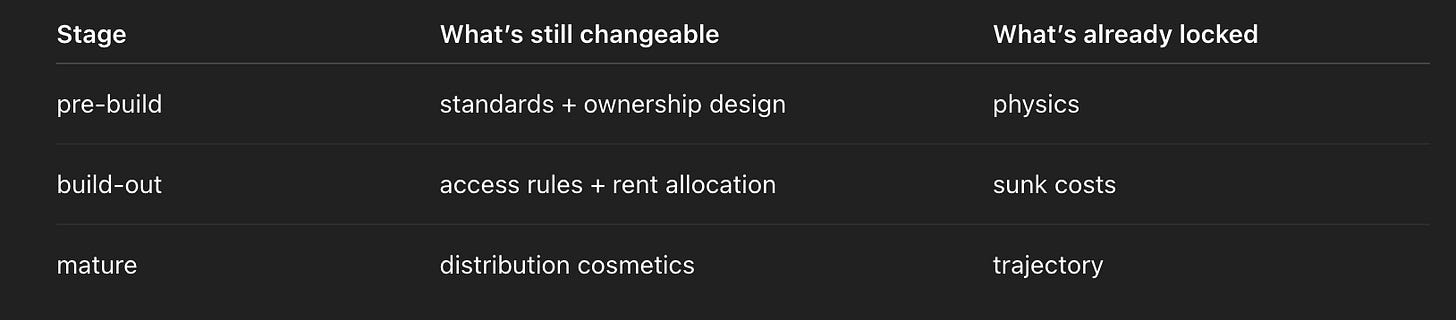

6.7 — The Narrow Corridor

Where improvement remains possible — and why it is narrower than believed.

6.7.1 Constraint as the Price of Survival

There is a narrow window where human agency still matters.

It is the window before the system locks in.

Once orbital infrastructure is built, once AI systems are deployed, once capital is concentrated, the window closes.

At that point, humans are no longer shaping the system.

They are negotiating terms within it.

The only way to preserve agency is to act while the system is still being built.

This requires:

Recognising the transition is happening (most people don’t). Understanding the constraints (most people won’t). Acting decisively (most people can’t).

The window is narrow. And it is closing.

6.7.2 Why Better Does Not Mean Fairer

You can make the vertical economy better.

You can reduce inequality. You can improve access. You can distribute wealth more evenly.

But none of these improvements will make it fair.

Because fairness requires autonomy.

And autonomy is incompatible with the level of control required to manage a vertical economy.

You can have a more equal vertical economy.

You cannot have a fair one.

6.7.3 Why Collapse Is Not the Only Alternative

The false choice presented by most discourse is:

Accept the vertical economy as it is, or collapse.

This is not true.

There is a narrow corridor where you can:

Build vertical infrastructure in a way that preserves human agency. Distribute the rents of vertical systems more equitably. Design the human role inside the system consciously, rather than by default.

This corridor is narrow. It requires moving fast, thinking clearly, and accepting that some people will lose.

But it is possible.

The alternative is not collapse. It is drift.

And drift leads to the worst of all outcomes: a system that is both extraordinarily productive and extraordinarily hostile to human flourishing.

6.8 — What History Will Say We Missed

The retrospective view.

6.8.1 The Signals Were Visible

History will not be kind to this era.

It will note that the signals were visible:

• when energy constraints throttled compute expansion • when automation substituted labour faster than institutions adapted • when vertical infrastructure outperformed horizontal systems on cost • when political systems argued over distribution before redesigning creation

They will point to charts, not speeches.

They will note that the moment labour’s share began its terminal decline, the system’s logic changed—and everyone pretended it hadn’t.

Not because people were ignorant.

Because acknowledging it would have required admitting that the old social contract had expired.

History is unsentimental about expired contracts.

6.8.2 We Confused Choice with Comfort

The central error of this era will not be described as malice or incompetence.

It will be described as comfort preservation.

Faced with structural change, societies mistook the ability to delay discomfort for the ability to choose outcomes.

They debated:

• fairness frameworks • ethical guidelines • regulatory principles • stakeholder inclusion • transition pacing

All important—and all downstream.

What they did not do early enough was redesign the human role inside a system that no longer needed human labour to function.

Comfort made delay feel responsible.

Delay made inevitability feel distant.

Distance made denial feel reasonable.

History will note the irony:

The more advanced a society was, the harder it found it to act—because its existing comforts were too expensive to jeopardise.

Choice was not lost suddenly.

It was traded away incrementally—in exchange for stability today.

6.8.3 The Cost of Waiting for Consensus

Consensus is a luxury of slow systems.

Vertical transitions are not slow.

They are driven by physics, cost curves, and optimisation loops that do not pause for alignment or moral clarity.

History will record that societies waited for:

• public agreement • political safety • electoral permission • moral consensus

And by the time those arrived, the system had already hardened.

Standards were set.

Infrastructure was deployed.

Capital was locked.

Interfaces were defined.

At that point, debate continued—but only cosmetically.

The greatest cost of waiting was not inefficiency.

It was loss of agency.

Once systems mature, humans stop shaping outcomes and start negotiating terms.

History is clear on this pattern:

Those who move early argue about design.

Those who move late argue about access.

And access is never free.

6.9 — The Future Was Not Taken — It Was Built

A closing without comfort or commands.

The future does not arrive as an event.

It arrives as accumulation.

Layer by layer.

Decision by decision.

Cost curve by cost curve.

No single moment marks the transition. There is no bell, no declaration, no clean before-and-after.

That is why so many believed the future was still open—long after it had already been engineered.

The vertical economy was not imposed.

It was constructed.

By engineers optimising efficiency.

By firms pursuing advantage.

By states seeking resilience.

By systems solving problems they were never asked to contextualise.

No villain planned it.

No committee approved it.

And yet here it is.

The great myth of this era will be that “we chose badly.”

History will be less forgiving.

It will say:

We chose locally.

We optimised narrowly.

We deferred integration.

We mistook momentum for neutrality.

The future that emerges from this transition will feel inevitable to those born into it.

That is always the final insult of history.

What was once debated becomes assumed.

What was once designed becomes invisible.

What was once fragile becomes default.

The vertical world will not announce itself as loss or liberation.

It will simply function.

Some humans will thrive inside it.

Some will adapt.

Some will be managed.

Not because of ideology—but because infrastructure expresses values long after rhetoric fades.

This book does not ask for hope.

It does not ask for resistance.

It does not offer salvation.

It offers clarity.

The system is not waiting.

The transition is not optional.

The outcomes are not neutral.

And the future was never something to be “taken.”

It was always something that would be built—by whoever understood the constraints first, and acted while choice still existed.

Whether humanity remains a co-author—or becomes a footnote—is not a question of belief.

It is a question of design.

And design, unlike hope, has deadlines.

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in the startup Investor ecosystem.

If you've got suggestions, an article, research, your tech stack, or a job listing you want featured, just let me know! I'm keen to include it in the upcoming edition.

Please let me know what you think of it, love a feedback loop 🙏🏼

🛑 Get a different job.

Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss an update.

For the ❤️ of startups

✌🏼 & 💙

Derek